Speech 1: DLRLSS 2019-James Wright: Multi-Agent Systems

Slides

In this talk:

-

Multi-agent systems are important and hard

-

Game theory: Multi-agent mathematics

-

Thinking realistically about multi-agent systems

-

Predicting human behaviour in normal-form games (Not included due to time)

More agents, more problems

Nobody ever says “maybe I should solve my problem with multi-agent systems!”

Multi-agent systems aren’t solutions. They are problems.

But they are problems that are important to solve.

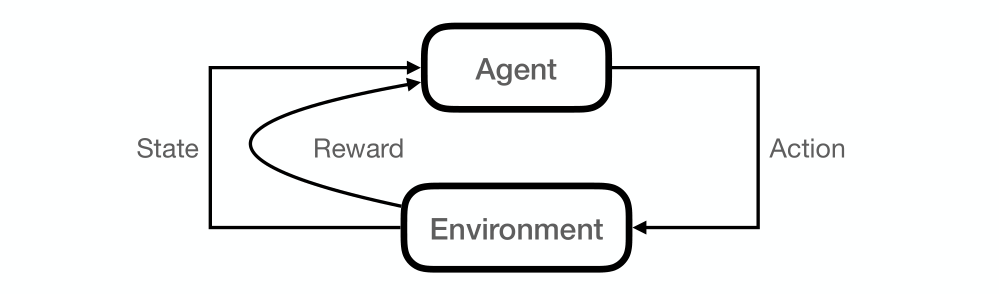

Single Agent Systems

1. An agent interacts with an environment by taking an action

2. Agent’s action and environment’s previous state determine:

-

Agent’s reward

-

Environment’s next state

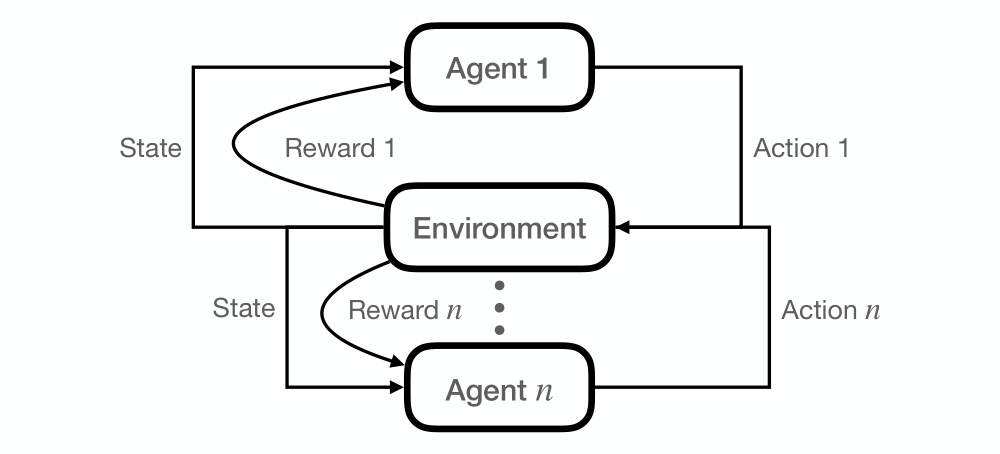

Multi-agent Systems

To change the single agent system to a multi-agent system, we need

-

Multiple autonomous agents

-

With distinct goals / priorities / rewards

Multi-agent Systems are Widespread

Multi-agent systems are everywhere:

-

Games (Poker, Go, Shogi, StarCraft)

-

Auctions (ad auctions, spectrum auctions)

-

Online platforms (sharing economy, crowdsourcing)

-

Cooperative interaction (language, advice, decision support)

-

Cooperative interaction (language, advice, decision support)

-

Kidney exchange

-

Urban planning

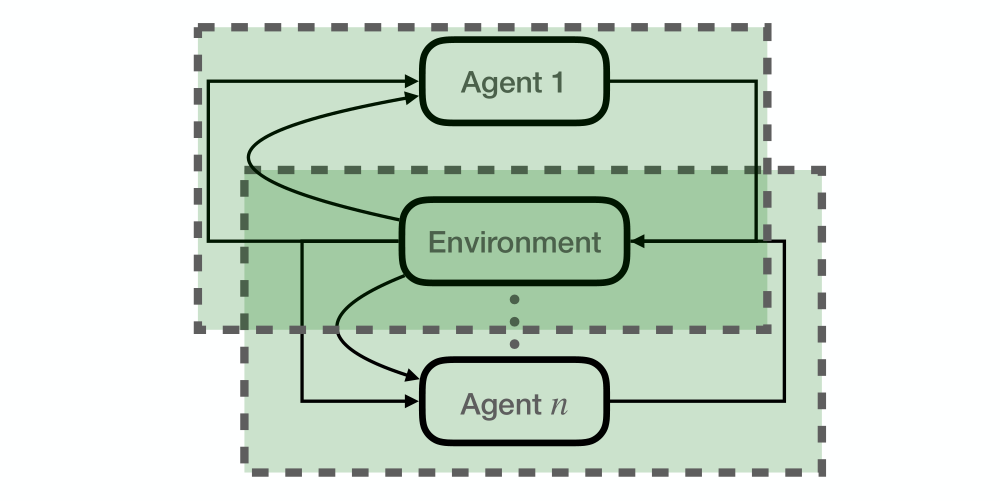

Multi-agent Systems are Nonstationary

Multi-agent systems are nonstationary in a special way because every agent is part of every other agent’s environment. Each agent may try to game the others and the environment changes in anticipation of agent’s actions. So the agent can’t do some straightforward learning on its environment.

Multi-agent Objectives are Often Unclear

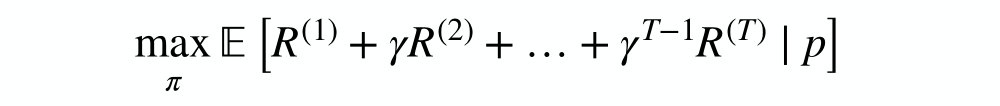

In a single-agent system:

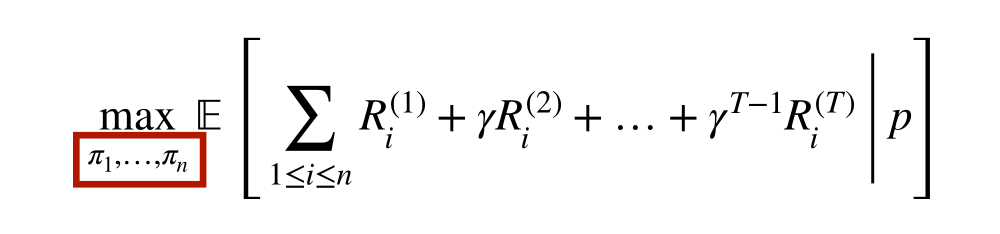

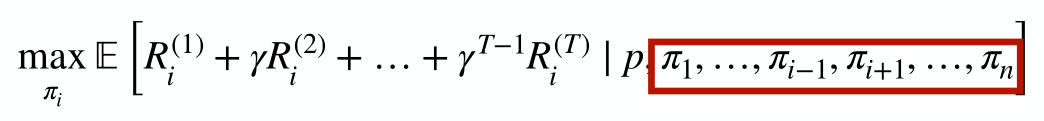

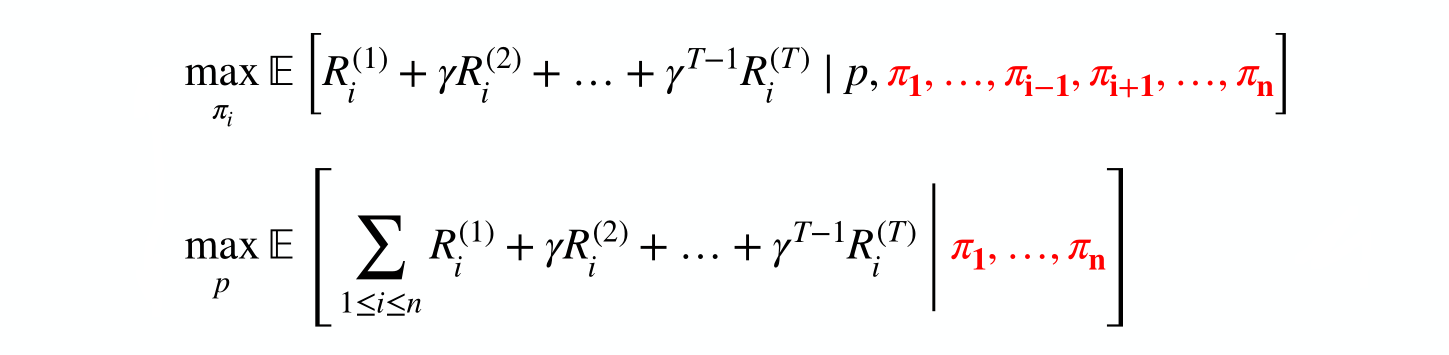

Maximize total reward over all the agents:

Multi-agent Objectives

Agent Design: Maximize individual agent’s reward

Mechanism Design: Maximize total reward by optimizing the environment

Both of these depend on the (other) agents’ policies!

(Noncooperative) Game Theory

It turns out that we can really precisely put our finger on a lot of these difficulties using game theory.

Game theory is amazing because it’s talking about multiple agents in math. Game theory is the mathematical study of interaction between multiple rational(理性的), self-interested(自利的) agents (these are two important assumptions):

-

Rational: Each agent maximizes their expected utility

-

Self-interested: Agents pursue only their own preferences

-

Not the same as “agents are psychopaths”!

Their preferences may include the well-being of other agents.- I make my own decision to make others happy. -

Rather, the agents are autonomous: they decide on their own priorities independently.

-

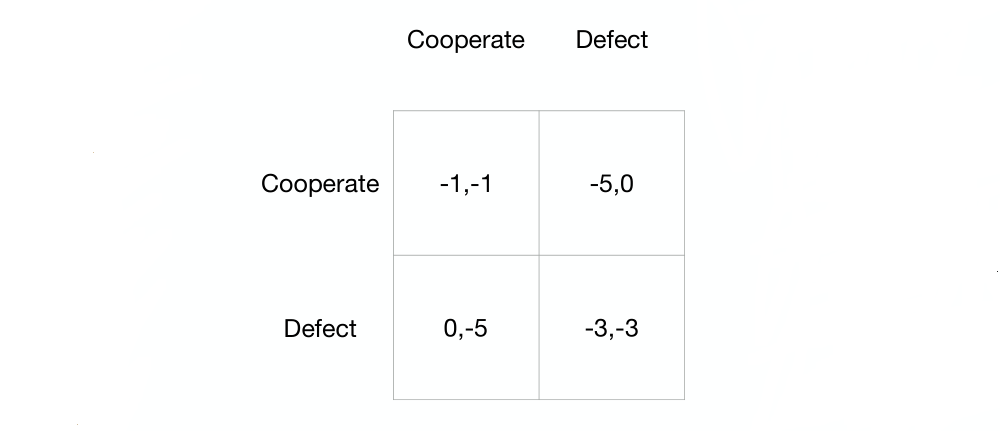

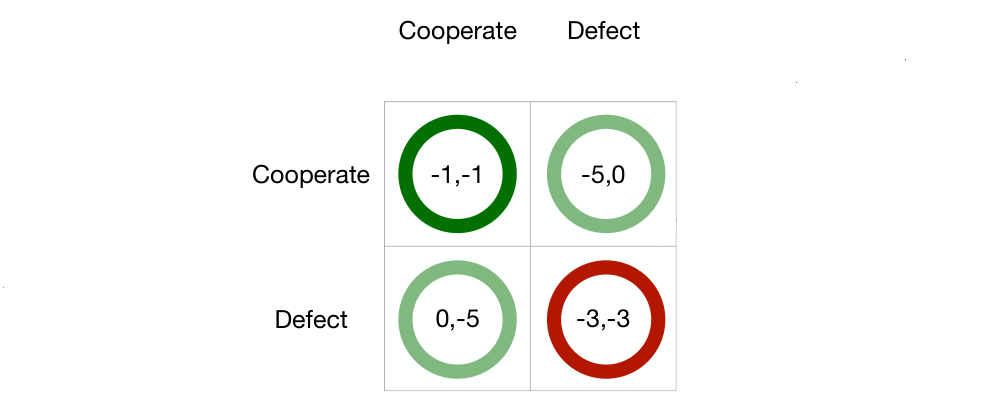

Fun Game: Prisoner’s Dilemma(囚徒困境)

Two suspects are being questioned separately by the police.

-

If they both remain silent (cooperate – i.e., with each other), then they will both be sentenced to 1 year on a lesser charge

-

If they both implicate each other (defect), then they will both receive a reduced sentence of 3 years

-

If one defects and the other cooperates, the defector is given immunity (0 years) and the cooperator serves a full sentence of 5 years.

Normal-Form Games

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is an example of a normal-form game, in which

-

Agents make a single decision simultaneously, and then receive a payoff depending on the profile of actions.

-

There are n players: N={1,2,…,n}, indexed by i.

-

Each player i has a set Ai of available actions.

-

A tuple a∈A=A1✖…✖An giving an action ai for each player i in an action profile

-

Each player i has a utility function ui: A → ℝ (their preferences)

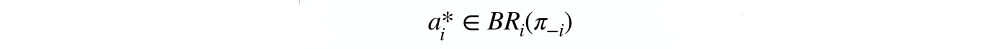

Maximize Individual Agent’s Rewards: Best Response

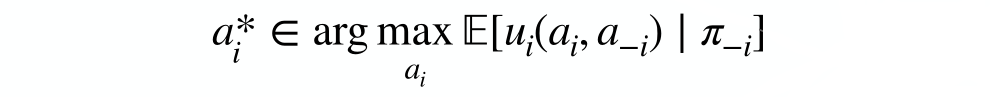

In game theory, a rational agent is one that maximizes their expected utility given their beliefs π_i about the other agents’ policies:

A shorter way to say this: ai* is a best response:

Nash Equilibrium(纳什均衡)

Where do the beliefs π_i come from?

Nash Equilibrium is the standard game theoretic prediction about what’s gonna happen in a multi-agent system.

Here’s how Nash Equilibrium works:

-

Every agent is perfectly rational

-

Therefore every agent is best responding to the actual policies of the other agents

-

Therefore πi(ai)>0 ⟹ ai∈BRi(π_i) for all i

Any profile π* of policies that satisfies (3) is a Nash equilibrium.

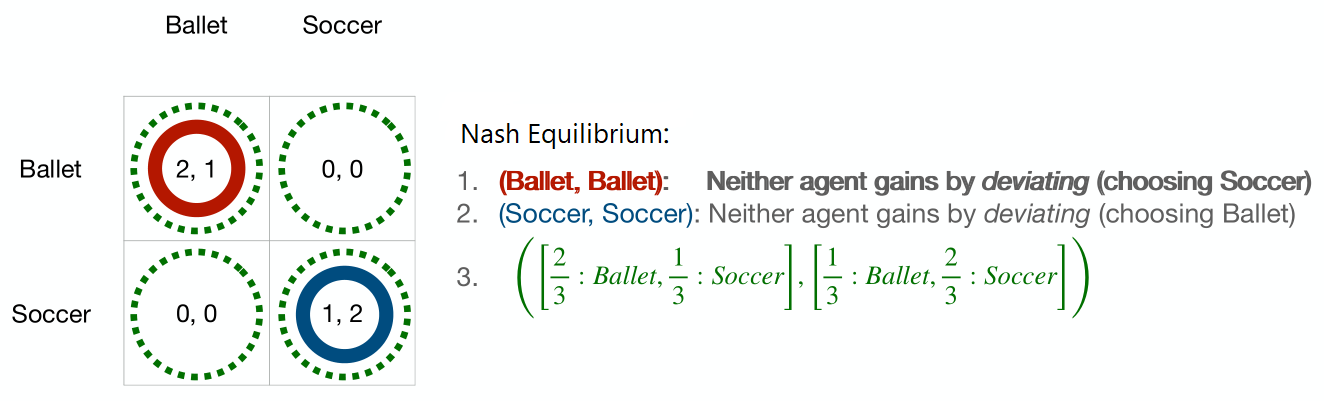

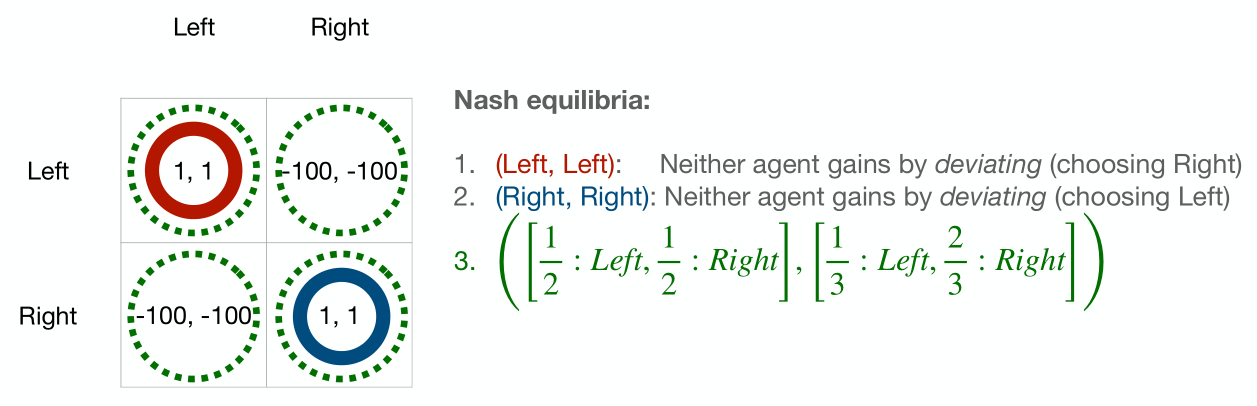

Nash Equilibrium Predictions

Every agent is perfectly rational, therefore every agent best responds to every other agent simultaneously (otherwise they’re behaving irrationally).

In this game, it turns out that there are more than one nash equilibrium. If the row player goes to the ballet with 2/3 probability and the column player goes to the ballet with 1/3 probability, that’s a equilibrium because it makes the expected utility for either action equal.

However, these predictions are not quite helpful and this is the first problem that game theory is going to point out to us. Nash equilibrium seems in some ways reasonable and it seems like everybody’s kind of doing the right thing, but if we actually want to know what to do, it’s telling us that we should either play one of our two actions or the other one, or maybe we should randomize between them.

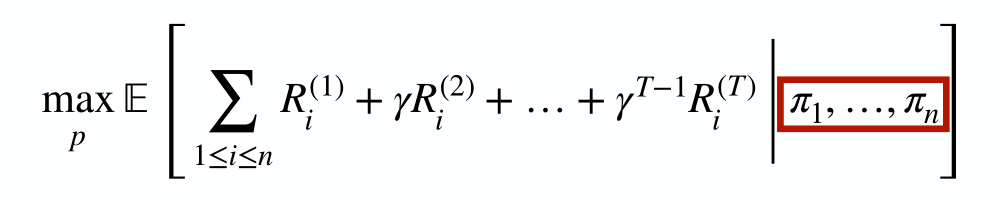

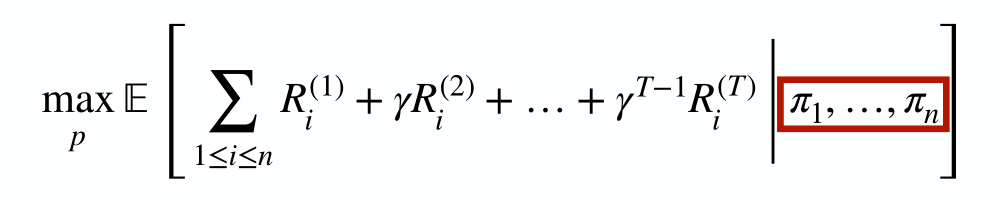

Maximize Total Reward?

Let’s come back to another issue.

Maybe we want everybody’s sum of rewards to be as big as it could possibly be and we are gonna do that by optimizing the environment (maximize over p).

Mechanism Design: Maximize total reward by optimizing the environment

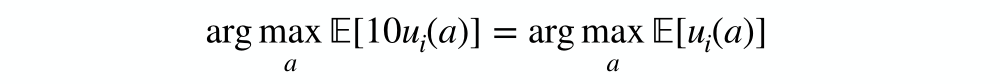

It turns out that utility values between agents can’t actually be add ed up. It’s not necessarily meaningful to add up the utility between agents because utilities are just representations of preferences and they just tell us how the agent is going to behave.

Agent i with utility ui and agent j with utility uj(a)=10ui(a) (every possible outcome) will behave in exactly the same way:

We can even add a arbitrary constant to everybody’s utility as well and it’ll also not change their behavior. So it’s not always straightforward to know how we can optimize the total utility.

If we can’s just add up utilities, then how should we reason about mechanism design? There are two answers and one answer which is often used in the real world is punting (like just counting everything in money). It’s kind of a reasonable approximation in some situations. Game theory has a theory about that, which is called Pareto Optimality

Pareto Optimality

This is a way of comparing even though we can’t compare individuals’ utilities. It basically consists of two definitions:

-

Pareto domination: A profile of utilities (x1,…,xn) Pareto dominates(支配) another profile (y1,…yn) if

-

xi is larger or equal to yi for every i∈N, and

-

There exists an i∈N such that xi is larger than yi (for some agents, that’s a strict inequality)

-

Every agent is at least as happy with x as with y, and at least one agent strictly prefers x to y.

-

-

Pareto optimality: An outcome (x1,…,xn) is Pareto optimal if it is not Pareto dominated by any other outcome.

-

Any outcome that is better for one agent must be worse for another

-

Why we talk about all of this? Because individually rational behaviour is not always globally optimal, we still need to consider the outcome of Nash equilibrium.

Individually Rational Behaviour is not Always Globally Optimal

We saw this with the prison dilemma.

-

Which outcome is Pareto optimal?

-

What is the Nash equilibrium (unique)?

The only equilibrium of Prisoner’s Dilemma is also the only outcome that is Pareto-dominated! - Both defecting.

Individual optimization can lead to the worst-possible global outcome.

That should worry us in the setting where we only get to control one agent and we only care about optimizing our own utility.

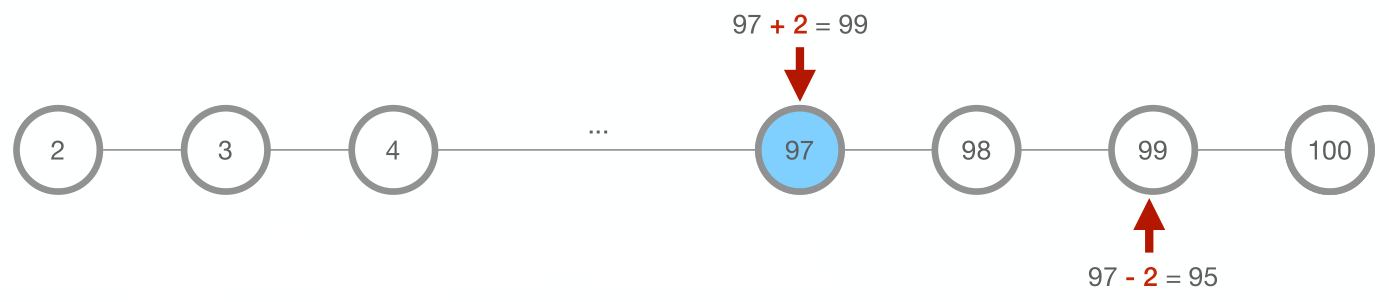

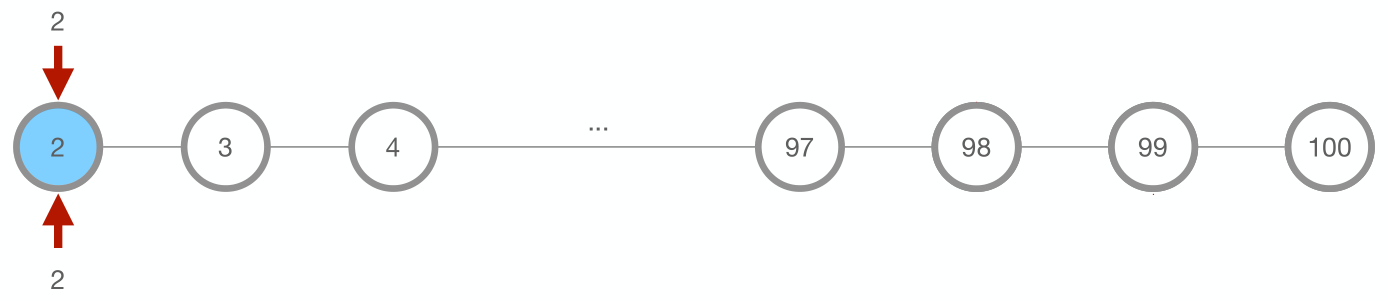

Fun Game: Traveller’s Dilemma(旅行者困境)

-

Two players pick a number (2-100) simultaneously

-

If they pick the same number x, then they both get $x payoff

-

If they pick different numbers:

-

Player who picked lower number gets lower number, plus bonus of $2

-

Player who picked higher number gets lower number, minus penalty of $2

-

We are talking about not only expected utility maximization, but also the equilibrium. Equilibrium says we are not just maximizing our expected utility, we are maximizing it with respect to believing that the player is also maximizing his expected utility. If we believe the other player is picking 100, we don’t believe he’s maximizing his expected utility.

It’s not surprising that the unique Nash equilibrium of Traveller’s Dilemma is two-two. Individual optimization can lead to the nearly worst-possible individual outcome.

This example convinced us that game theory was somehow missing something. If we are perfectly rational, we’ll reliably lose money. In what sense is that perfect rationality?

Nash Equilibrium vs. Humans

-

Nash equilibrium often makes counterintuitive(反直觉) predictions.

-

In Traveller’s Dilemma: The vast majority of human players choose 97–100. The Nash equilibrium is 2.

-

-

Modifications to a game that don’t change Nash equilibrium predictions at all can cause large changes in how human subjects play the game

-

In Traveller’s Dilemma: When the penalty is large, people play much closer to Nash equilibrium.

-

But the size of the penalty does not change the equilibrium!

-

-

Clearly Nash equilibrium does not capture the whole story (for humans)

Multiple Nash Equilibria

Multiple equilibria are a problem even in perfectly cooperative games.

The game theory doesn’t even tell us what side of road we should drive on.

Best Response is Expensive

All of the previous problems arise in very simple games, but in many settings (Poker, Go, Chess) we can’t even reliably compute BRi.

What’s Going Wrong Here?

Why is game theory failing us so badly? Two kinds of problems.

-

We can’t do what game theory prescribes, and neither can the other players (best responce - how?)

-

Finding a Nash equilibrium is computationally hard

-

-

Nash equilibrium is about what satisfies certain conditions (very post hoc), not how you get there

-

Hence multiple, unordered (no comparison) equilibria

-

-

Unrestricted individual optimization can cause

even small misalignmentsin interests to snowball.

Thinking About the Problem

Three ways of viewing a multi-agent problem:

-

Normative(规范性)

-

Descriptive

-

Positive

We have to think really carefully about what we’re trying to do in a multi-agent system. We should never just pick some loss function off the shelf.

Normative Modeling

-

Start from axioms (assumptions) and derive consequences:

-

Every agent maximizes expected utility

-

Every agent has accurate beliefs

-

-

Game theory problems come from:

-

Violation of these assumptions

-

Focus on consequences rather than process

-

Descriptive Modeling

Construct a model of how agents actually behave (rational but not perfect)

-

Need a descriptive model of other players to evaluate algorithm performance:

-

Understanding human behavior can give insight into bounded rationality

Positive Modeling

Given a descriptive model of behaviour and environment, figure out how to achieve a goal

-

Agent Design: Design an agent that will achieve its individual goals:

-

Maximum-value bundle of goods, winning a game

-

-

Mechanism Design: Design an environment for agents such that the agents’ collective actions will achieve a goal:

-

Markets, online platforms, auctions, Internet protocols

-

Final Thoughts

-

Our lives are increasingly part of novel multi-agent systems

-

It is imperative that we understand their properties so we can design them properly

-

-

This is a wide-open research area

-

We don’t even have a coherent notion of optimal behaviour yet

-

-

Game theory helps us reason precisely about multi-agent interactions, but it isn’t enough

-

Need real-world descriptive models and a theory of how to use them