Paper 5: Curiosity-driven Exploration by Self-supervised Prediction (ICM)

Zhihu Blog

Abstract

-

In many real-world scenarios, rewards extrinsic to the agent are extremely sparse, or absent altogether. In such cases, curiosity can serve as an intrinsic reward signal to enable the agent to explore its environment and learn skills that might be useful later in its life.

-

We formulate curiosity as the error in an agent’s ability to predict the consequence of its own actions in a visual feature space learned by a self-supervised inverse dynamics model.

-

The proposed approach is evaluated in two environments: VizDoom and Super Mario Bros. Three broad settings are investigated: sparse extrinsic reward; no extrinsic reward; generalization to unseen scenarios.

1 Introduction

In many real-world scenarios, rewards extrinsic to the agent are extremely sparse or missing altogether, and it is not possible to construct a shaped reward function. This is a problem as the agent receives reinforcement for updating its policy only if it succeeds in reaching a prespecified goal state. Hoping to stumble into a goal state by chance (i.e. random exploration) is likely to be futile for all but the simplest of environments.

In reinforcement learning, intrinsic motivation/rewards become critical whenever extrinsic rewards are sparse. Most formulations of intrinsic reward can be grouped into two broad classes: 1) encourage the agent to explore “novel” states; 2) encourage the agent to perform actions that reduce the error/uncertainty in the

agent’s ability to predict the consequence of its own actions (i.e. its knowledge about the environment).

This work belongs to the broad category of methods that generate an intrinsic reward signal based on how hard it is for the agent to predict the consequences of its own actions, i.e. predict the next state given the current state and the executed action. However, we manage to escape most pitfalls of previous prediction approaches with the following key insight: we only predict those changes in the environment that could possibly be due to the actions of our agent or affect the agent, and ignore the rest. That is, instead of making predictions in the raw sensory space (e.g. pixels), we transform the sensory input into a feature space where only the information relevant to the action performed by the agent is represented. We learn this feature space using self-supervision – training a neural network on a proxy inverse dynamics task of predicting the agent’s action given its current and next states. Since the neural network is only required to predict the action, it has no incentive to represent within its feature embedding space the factors of variation in the environment that do not affect the agent itself. We then use this feature space to train a forward dynamics model that predicts the feature representation of the next state, given the feature representation of the current state and the action. We provide the prediction error of the forward dynamics model to the agent as an intrinsic reward to encourage its curiosity.

In our opinion, curiosity has three fundamental uses:

-

The role of curiosity has been widely studied in the context of solving tasks with

parse rewards. -

Curiosity helps an agent explore its environment in the quest for

new knowledge(a desirable characteristic of exploratory behavior is that it should improve as the agent gains more knowledge). -

Curiosity is a mechanism for an agent to learn skills that might be helpful in

future scenarios.

In this paper, we evaluate the effectiveness of our curiosity formulation in all three of these roles.

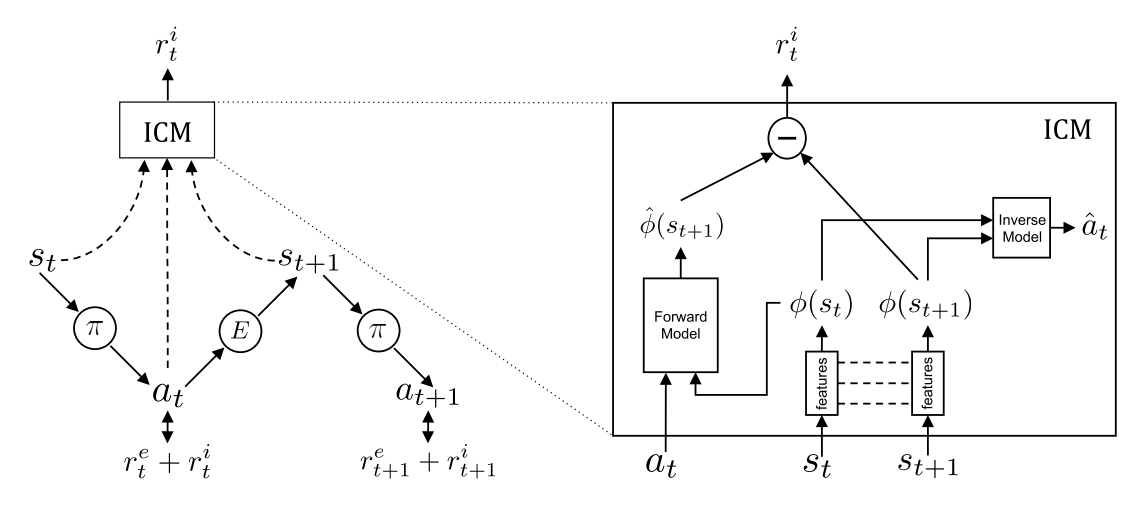

2 Curiosity-Driven Exploration

Our agent is composed of two subsystems: a reward generator that outputs a curiosity-driven intrinsic reward signal and a policy that outputs a sequence of actions to maximize that reward signal. In addition to intrinsic rewards, the agent optionally may also receive some extrinsic reward from the environment. The policy sub-system is trained to maximize the sum of these two rewards

with the extrinsic reward mostly (if not always) zero.

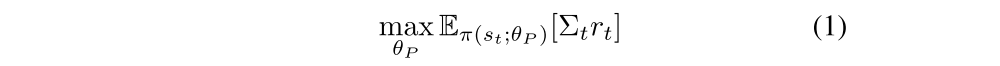

We represent the policy π(st; θP) by a deep neural network with parameters θP, which is optimized to maximize the expected sum of rewards,

Our curiosity reward model can potentially be used with a range of policy learning methods, such as A3C. Our main contribution is in designing an intrinsic reward signal based on prediction error of the agent’s knowledge about its environment that scales to high-dimensional continuous state spaces like images, bypasses the hard problem of predicting pixels and is unaffected by the unpredictable aspects of the environment that do not affect the agent.

2.1 Prediction error as curiosity reward

We shouldn’t consider using prediction error in the pixel space as the curiosity reward. The pixel prediction error will remain high

and the agent will always remain curious about something inconsequential. The underlying problem is that the agent is unaware that some parts of the state space simply cannot be modeled and thus the agent can fall into an artificial curiosity trap and stall its exploration.

If not the raw observation space, then what is the right feature space for making predictions so that the prediction error provides a good measure of curiosity? To answer this question, let us divide all sources that can modify the agent’s observations into three cases: (1) things that can be controlled by the agent; (2) things that the agent cannot control but that can affect the agent; (3) things out of the agent’s control and not affecting the agent. A good feature space for curiosity should model (1) and (2) and be unaffected by (3). This latter is because, if there is a source of variation that is inconsequential for the agent, then the agent has no incentive to know about it.

2.2. Self-supervised prediction for exploration

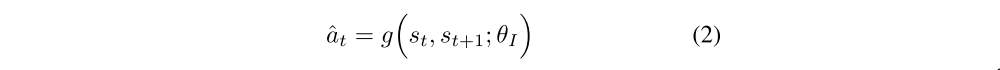

Our aim is to come up with a general mechanism for learning feature representations such that the prediction error in the learned feature space provides a good intrinsic reward signal. We propose that such a feature space can be learned by training a DNN with two sub-modules: the first sub-module encodes the raw state (st) into a feature vector φ(st) and the second sub- module takes as inputs the feature encoding φ(st), φ(st+1) of two consequent states and predicts the action (at) taken by the agent to move from state st to st+1. Training this neural network amounts to learning function g defined as:

where, ˆat is the predicted estimate of the action at and the the neural network parameters θI are trained to optimize,

this is the loss function that measures the discrepancy between the predicted and actual actions. In case at is discrete, the output of g is a soft-max distribution across all possible actions and minimizing LI amounts to maximum likelihood estimation of θI under a multinomial(多项式) distribution. The learned function g is also known as the inverse dynamics model and the tuple (st, at, st+1) required to learn g is obtained while the agent interacts with the environment using its current policy π(s).

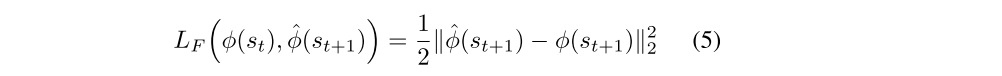

We also need to train another neural network that takes as inputs at and φ(st) and predicts the feature encoding of the state at time step t+1,

where ˆφ(st+1) is the predicted estimate of φ(st+1) and the neural network parameters θF are optimized by minimizing the loss function LF:

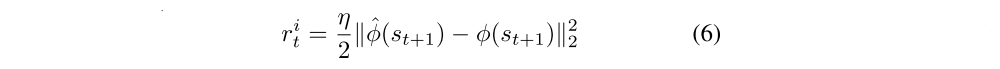

The learned function f is also known as the forward dynamics model. The intrinsic reward signal is computed as,

where η > 0 is a scaling factor. In order to generate the curiosity based intrinsic reward signal, we jointly optimize the forward and inverse dynamics loss described in equations 3 and 5 respectively. The inverse model learns a feature space that encodes information relevant for predicting the agent’s actions only and the forward model makes predictions in this feature space. We refer to this proposed curiosity formulation as Intrinsic Curiosity Module (ICM). As there is no incentive for this feature space to encode any environmental features that are not influenced by the agent’s actions, our agent will receive no rewards for reaching environmental states that are inherently unpredictable and its exploration strategy will be robust to the presence of distractor objects, changes in illumination, or other nuisance sources of variation in the environment. The following figure is the illustration of the formulation.

We make use of the error in the forward model predictions as the curiosity reward for training our agent’s policy.

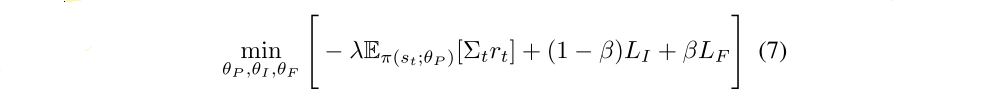

The overall optimization problem that is solved for learning the agent is a composition of equations 1, 3 and 5 and can be written as,

where 0 ≤ β ≤ 1 is a scalar that weighs the inverse model loss against the forward model loss and λ > 0 is a scalar that weighs the importance of the policy gradient loss against the importance of learning the intrinsic reward signal.

Take away: The agent in state st interacts with the environment by executing an action at sampled from its current policy π and ends up in the state st+1. The policy π is trained to optimize the sum of the extrinsic reward provided by the environment E and the curiosity based intrinsic reward signal generated by our proposed Intrinsic Curiosity Module (ICM). ICM encodes the states st, st+1 into the features φ(st), φ(st+1) that are trained to predict at (i.e. inverse dynamics model). The forward model takes as inputs φ(st) and at and predicts the feature representation ˆφ(st+1) of st+1. The prediction error in the feature space is used as the curiosity based intrinsic reward signal. As there is no incentive for φ(st) to encode any environmental features that can not influence or are not influenced by the agent’s actions, the learned exploration strategy of our agent is robust to uncontrollable aspects of the environment.

3 Experimental Setup

I studied this part carefully because I wanted to train an agent to play Street Fighter III Third Strike with ICM and the A3C algorithm.

-

Environments:

-

VizDoom

-

Super Mario Bros

-

-

Training details: All agents in this work are trained using visual inputs that are preprocessed.

-

The input RGB images are converted into gray-scale and resized to 42 × 42

-

In order to model temporal dependencies, the state representation (st) of the environment is constructed by concatenating the current frame with the three previous frames

-

Use action repeat of four during training time in VizDoom and action repeat of six in Mario. Sample the policy without any action repeat during inference

-

Following the asynchronous training protocol in A3C, all the agents were trained asynchronously with twenty workers using stochastic gradient descent

-

Use Adam optimizer with its parameters not shared across the workers

-

-

A3C architecture: The input state st is passed through a sequence of four convolution layers with 32 filters each, kernel size of 3x3, stride of 2 and padding of 1. An exponential linear unit (ELU) is used after each convolution layer. The output of the last convolution layer is fed into a LSTM with 256 units. Two seperate fully connected layers are used to predict the value function and the action from the LSTM feature representation.

-

Intrinsic Curiosity Module (ICM) architecture: This module consists of the forward and the inverse model.

-

The inverse model first maps the input state (st) into a feature vector φ(st) using a series of four convolution layers, each with 32 filters, kernel size 3x3, stride of 2 and padding of 1. ELU non-linearity is used after each convolution layer. The dimensionality of φ(st) is 288. For the inverse model, φ(st) and φ(st+1) are concatenated into a single feature vector and passed as inputs into a fully connected layer of 256 units followed by an output fully connected layer with 4 units to predict one of the four possible actions.

-

The forward model is constructed by concatenating φ(st) with at and passing it into a sequence of two fully connected layers with 256 and 288 units respectively. The value of β is 0.2, and λ is 0.1. The Equation (7) is minimized with learning rate of 1e− 3.

-