Paper 10: Multi-Agent Actor-Critic for Mixed Cooperative-Competitive Environments (MADDPG)

Abstract

-

We explore deep reinforcement learning methods for multi-agent domains.

-

We present an adaptation of actor-critic methods that considers action policies of other agents and is able to successfully learn policies that require complex multi- agent coordination.

-

We introduce a training regimen utilizing an ensemble of policies for each agent that leads to more robust multi-agent policies.

1 Introduction

Most of the successes of RL have been in single agent domains, where modelling or predicting the behaviour of other actors in the environment is largely unnecessary.

Variants of hierarchical RL can also be seen as a multi-agent system, with multiple levels of hierarchy being equivalent to multiple agents.

Successfully scaling RL to environments with multiple agents is crucial to building AI systems that can productively interact with humans and each other.

Traditional reinforcement learning approaches are poorly suited to multi-agent environments. One issue is that each agent’s policy is changing as training progresses, and the environment becomes non-stationary from the perspective of any individual agent.

-

This presents learning stability challenges and prevents the straightforward use of past

experience replaywhich is crucial for stabilizing deep Q-learning. -

Policy gradient methods, on the other hand, usually exhibit very

high variancewhen coordination of multiple agents is required. -

One can use model-based policy optimization which can learn optimal policies via back-propagation, but this requires a (differentiable)

model of the world dynamicsand assumptions about the interactions between agents.

In this work, we propose a general-purpose multi-agent learning algorithm that:

-

leads to learned policies that only use their own observations at execution time

-

does not assume a differentiable model of the environment dynamics or any particular structure on the communication method between agents

-

is applicable not only to cooperative interaction but to competitive or mixed interaction involving both physical and communicative behavior

We adopt the framework of centralized training with decentralized execution(集中训练分散执行), allowing the policies to use extra information to ease training, so long as this information is not used at test time. We propose a simple extension of actor-critic policy gradient methods where the critic is augmented with extra information about the policies of other agents, while the actor only has access to local information. After training is completed, only the local actors are used at execution phase, acting in a decentralized manner and equally applicable in cooperative and competitive settings.

Since the centralized critic function explicitly uses the decision-making policies of other agents, we additionally show that agents can learn approximate models of other agents online and effectively use them in their own policy learning procedure. We also introduce a method to improve the stability of multi-agent policies by training agents with an ensemble of policies, thus requiring robust interaction with a variety of collaborator and competitor policies.

3 Background

-

Markov Games

In this work, we consider a multi-agent extension of Markov decision processes (MDPs) called partially observable Markov games. A Markov game for N agents is defined by a set of states S describing the possible configurations of all agents, a set of actions A1, …, AN and a set of observations O1, …, ON for each agent. To choose actions, each agent uses a stochastic policy, which produces the next state according to the state transition function. Each agent obtains rewards as a function of the state and agent’s action and receives a private observation correlated with the state. The initial states are determined by a distribution. Each agent aims to maximize its own total expected return.

-

Q-Learning and Deep Q-Networks (DQN)

Q-Learning can be directly applied to multi-agent settings by having each agent learn an independently optimal function Q. However, because agents are independently updating their policies as learning progresses, the environment appears non-stationary from the view of any one agent, violating Markov assumptions required for convergence of Q-learning. Another difficulty is that the experience replay buffer cannot be used in such a setting since in general.

-

Policy Gradient (PG) Algorithms

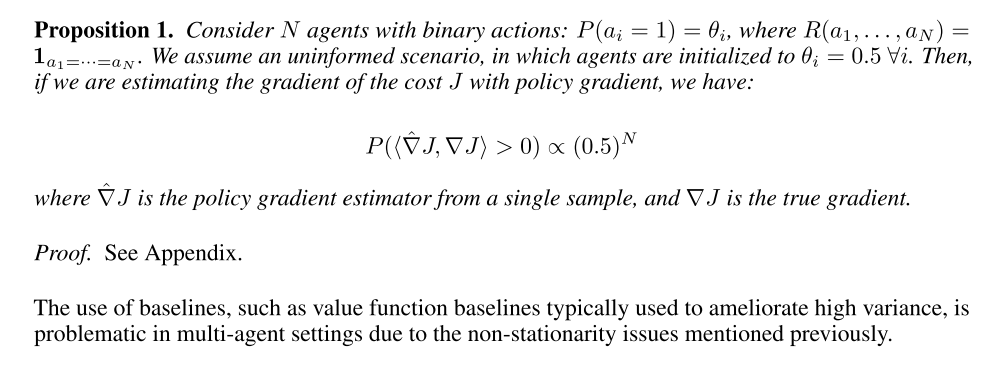

Policy gradient methods are known to exhibit high variance gradient estimates. This is exacerbated(加重)in multi-agent settings; since an agent’s reward usually depends on the actions of many agents, the reward conditioned only on the agent’s own actions exhibits much more variability, thereby increasing the variance of its gradients. Below, we show a simple setting where the probability of taking a gradient step in the correct direction decreases exponentially with the number of agents.

-

Deterministic Policy Gradient (DPG) Algorithms.

It is also possible to extend the policy gradient framework to deterministic policies µθ : S → A. In particular, under certain conditions we can write the gradient of the objective as:

it requires that the action space A (and thus the policy µ) be continuous.

Deep deterministic policy gradient (DDPG) is a variant of DPG where the policy µ and critic Qµ are approximated with deep neural networks. DDPG is an off-policy algorithm, and samples trajectories from a replay buffer of experiences that are stored throughout training. DDPG also makes use of a target network.

4 Methods

4.1 Multi-Agent Actor Critic

Our goal in this section is to derive an algorithm that works well in multi-agent settings. However, we would like to operate under the following constraints:

-

the learned policies can

only use their own observationsat execution time -

we do not assume a differentiable

model of the environment dynamics -

we do not assume any particular

structure on the communication method between agents(that is, we don’t assume a differentiable communication channel)

Fulfilling the above would provide a general-purpose multi-agent learning algorithm that could be applied not just to cooperative games with explicit communication channels, but competitive games and games involving only physical interactions between agents.

We accomplish our goal by adopting the framework of centralized training with decentralized execution. We allow the policies to use extra information to ease training, so long as this information is not used at test time. We propose a simple extension of actor-critic policy gradient methods where the critic is augmented with extra information about the policies of other agents.

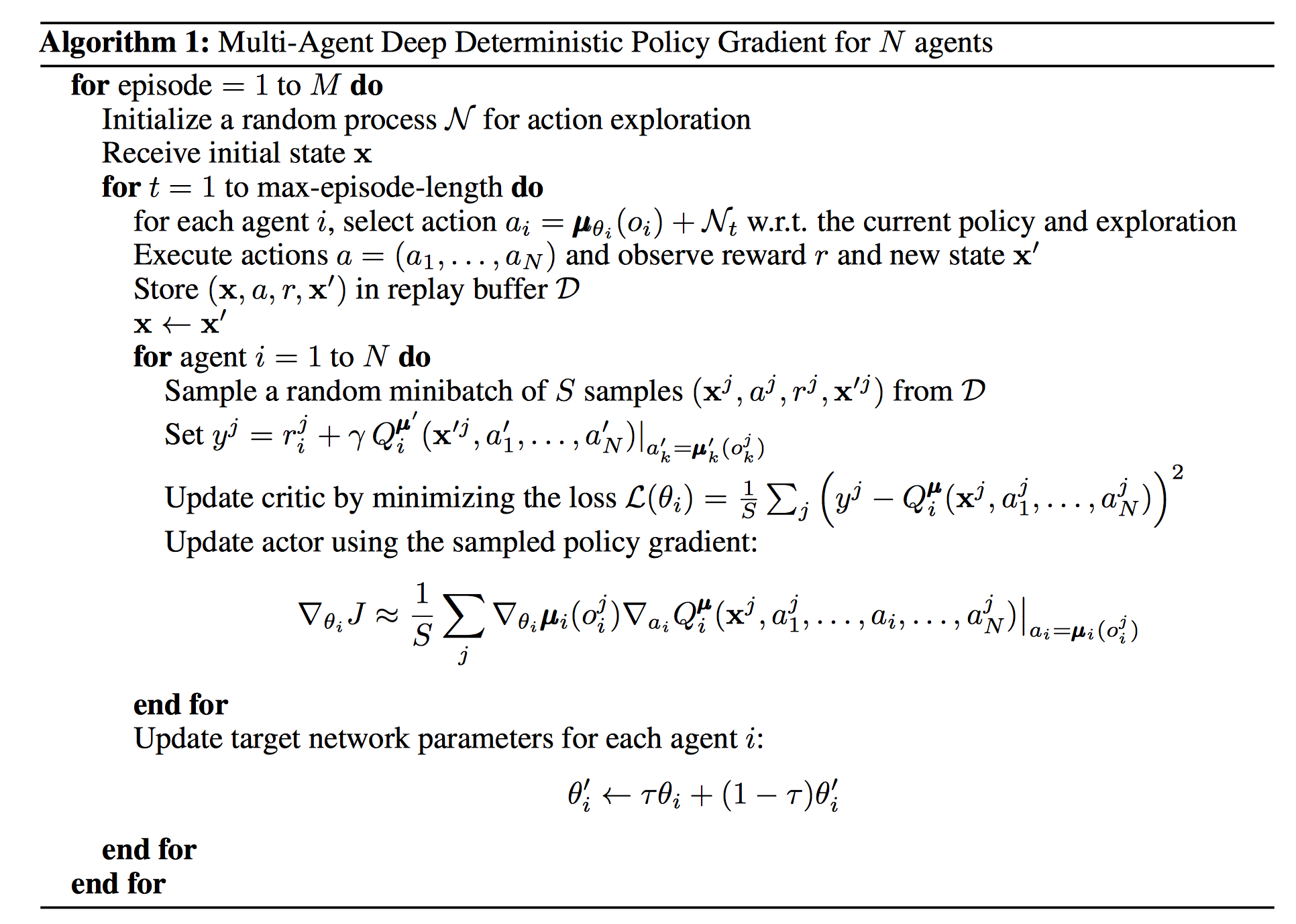

Consider a game with N agents with policies parameterized by θ = {θ1, …, θN}, and let π = {π1, …, πN} be the set of all agent policies. Then we can write the gradient of the expected return for agent i as:

Here Qπi(x, a1, …, aN) is a centralized action-value function that takes as input the actions of all agents, a1, . . . , aN, in addition to some state information x, and outputs the Q-value for agent i. In the simplest case, x could consist of the observations of all agents, x = (o1, …, oN), however we could also include additional state information if available. Since each Qπi is learned separately, agents can have arbitrary reward structures, including conflicting rewards in a competitive setting.

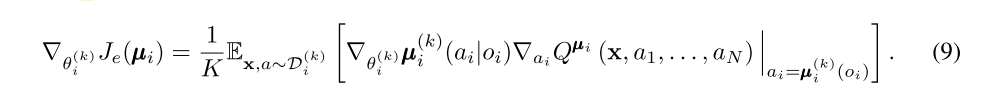

We can extend the above idea to work with deterministic policies. If we now consider N continuous policies µθi, the gradient can be written as:

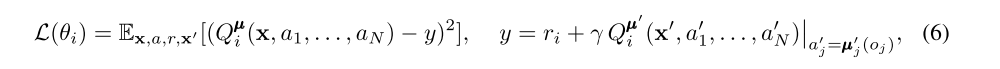

Here the experience replay buffer D contains the tuples (x, x’, a1, . . . , aN, r1, . . . , rN), recording experiences of all agents. The centralized action-value function Qµi is updated as:

where µ’ = {µθ’1, …, µθ’N} is the set of target policies with delayed parameters θ’i.

A primary motivation behind MADDPG is that, if we know the actions taken by all agents, the environment is stationary even as the policies change, since P(s’|s, a1, …, aN, π1, …, πN) = P(s’|s, a1, …, aN) = P(s’|s, a1, …, aN, π’1, …, π’N) for any πi ≠ π’i.

Note that we require the policies of other agents to apply an update in Eq. 6. Knowing the observations and policies of other agents is not a particularly restrictive assumption; if our goal is to train agents to exhibit complex communicative behaviour in simulation, this information is often available to all agents. However, we can relax this assumption if necessary by learning the policies of other agents from observations — we describe a method of doing this in Section 4.2.

4.2 Inferring Policies of Other Agents

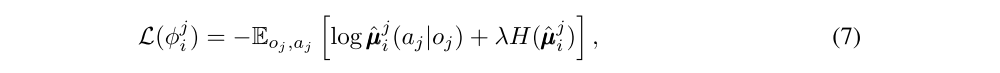

To remove the assumption of knowing other agents’ policies, each agent i can additionally maintain an approximation to the true policy of agent j, µj. φ are the parameters of the approximation. This approximate policy is learned by maximizing the log probability of agent j’s actions, with an entropy regularizer:

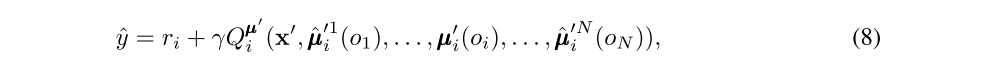

where H is the entropy of the policy distribution. With the approximate policies, y in Eq. 6 can be replaced by an approximate value ˆy calculated as follows:

Note the target network for the approximate policy. Eq. 7 can be optimized in a completely online fashion: before updating Qµi, the centralized Q function, we take the latest samples of each agent j from the replay buffer to perform a single gradient step to update φji. We also input the action log probabilities of each agent directly into Q, rather than sampling.

4.3 Agents with Policy Ensembles

A recurring problem in multi-agent reinforcement learning is the environment non-stationarity due to the agents’ changing policies. This is particularly true in competitive settings, where agents can derive a strong policy by overfitting to the behavior of their competitors. Such policies are undesirable as they are brittle(脆弱的)and may fail when the competitors alter(变更)their strategies.

To obtain multi-agent policies that are more robust to changes in the policy of competing agents, we propose to train a collection of K different sub-policies. At each episode, we randomly select one particular sub-policy for each agent to execute. Suppose that policy µi is an ensemble of K different sub-policies. For agent i, we are then maximizing the ensemble objective:

Since different sub-policies will be executed in different episodes, we maintain a replay buffer for each sub-policy of agent i. Accordingly, we can derive the gradient of the ensemble objective with respect to θ as follows: