Paper 15: Soft Actor-Critic: Off-Policy Maximum Entropy Deep Reinforcement Learning with a Stochastic Actor (SAC)

Abstract

-

Model-free DRL algorithms typically suffer from two major challenges: very high sample complexity and brittle convergence properties, which necessitate meticulous(细致的)hyperparameter tuning.

-

We propose soft actor-critic, an off-policy actor-critic DRL algorithm based on the maximum entropy (act as randomly as possible) reinforcement learning framework.

-

Our method combines off-policy updates with a stable stochastic actor-critic formulation.

1 Introduction

Widespread adoption of model-free DRL algorithms in real-world domains has been hampered by two major challenges.

-

First, these methods are

notoriously expensive in terms of their sample complexity. Even relatively simple tasks can require millions of steps of data collection, and complex behaviors with high dimensional observations might need substantially more. -

Second, these methods are often

brittle with respect to their hyperparameters: learning rates, exploration constants, and other settings must be set carefully for different problem settings to achieve good results.

Both of these challenges severely limit the applicability of model-free DRL to real-world tasks.

One cause for the poor sample efficiency of DRL methods is on-policy learning. Off-policy algorithms aim to reuse past experience. Unfortunately, the combination of off-policy learning and high-dimensional, nonlinear function approximation with neural networks presents a major challenge for stability and convergence.

We explore how to design an efficient and stable model-free DRL algorithm for continuous state and action spaces. To that end, we draw on the maximum entropy framework, which augments the standard maximum reward reinforcement learning objective with an entropy maximization term.

In this paper, we demonstrate that we can devise an off-policy maximum entropy actor-critic algorithm, which we call soft actor-critic (SAC), which provides for both sample-efficient learning and stability. We present a convergence proof for policy iteration in the maximum entropy framework, and then introduce a new algorithm based on an approximation to this procedure that can be practically implemented with deep neural networks, which we call soft actor-critic.

3 Preliminaries

We first introduce notation and summarize the standard and maximum entropy reinforcement learning frameworks.

3.1 Notation

3.2 Maximum Entropy Reinforcement Learning

Standard RL maximizes the expected sum of rewards

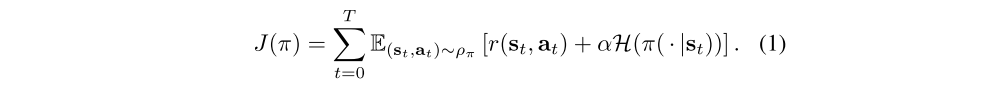

We’ll consider a more general maximum entropy objective, which favors stochastic policies by augmenting the objective with the expected entropy of the policy over ρπ(st):

The temperature parameter α determines the relative importance of the entropy term against the reward, and thus controls the stochasticity of the optimal policy. The maximum entropy objective differs from the standard maximum expected reward objective used in conventional(传统的)reinforcement learning, though the conventional objective can be recovered in the limit as α → 0. For the rest of this paper, we will omit(省略)writing the temperature explicitly, as it can always be subsumed(归入)into the reward by scaling it by α−1.

This objective has a number of conceptual and practical advantages.

-

First, the policy is incentivized(激励)to explore more widely, while giving up on clearly unpromising avenues.

-

Second, the policy can capture multiple modes of near-optimal behavior. In problem settings where multiple actions seem equally attractive, the policy will commit equal probability mass to those actions.

-

Lastly, prior work has observed improved exploration with this objective, and in our experiments, we observe that it considerably improves learning speed over state-of-art methods that optimize the conventional RL objective function.

We can extend the objective to infinite horizon problems by introducing a discount factor γ to ensure that the sum of expected rewards and entropies is finite.

We will discuss how we can devise a soft actor-critic algorithm through a policy iteration formulation, where we instead evaluate the Q-function of the current policy and update the policy through an off-policy gradient update. Though such algorithms have previously been proposed for conventional reinforcement learning, our method is, to our knowledge, the first off-policy actor-critic method in the maximum entropy reinforcement learning framework.

4 From Soft Policy Iteration to Soft Actor-Critic

Our off-policy soft actor-critic algorithm can be derived starting from a maximum entropy variant of the policy iteration method. We will first present this derivation, verify that the corresponding algorithm converges to the optimal policy from its density class, and then present a practical deep reinforcement learning algorithm based on this theory.

4.1 Derivation of Soft Policy Iteration

We will begin by deriving soft policy iteration, a general algorithm for learning optimal maximum entropy policies that alternates between policy evaluation and policy improvement in the maximum entropy framework. Our derivation is based on a tabular setting, to enable theoretical analysis and convergence guarantees, and we extend this method into the general continuous setting in the next section. We will show that soft policy iteration converges to the optimal policy within a set of policies which might correspond, for instance, to a set of parameterized densities.

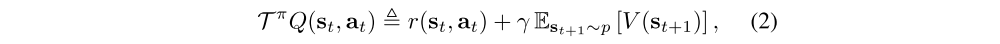

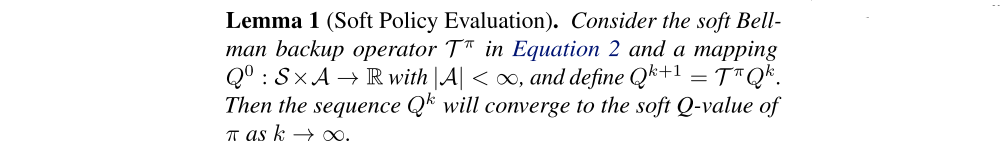

In the policy evaluation step of soft policy iteration, we wish to compute the value of a policy π according to the maximum entropy objective in Equation 1. For a fixed policy, the soft Q-value can be computed iteratively, starting from any function Q : S × A → R and repeatedly applying a modified Bellman backup operator Tπ given by

where

is the soft state value function. We can obtain the soft value function for any policy π by repeatedly applying Tπ as formalized below.

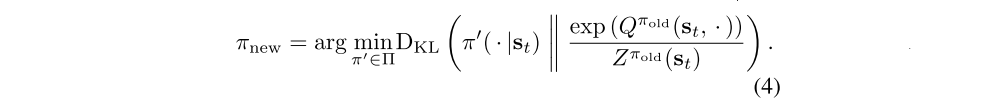

In the policy improvement step, we update the policy towards the exponential of the new Q-function. This particular choice of update can be guaranteed to result in an improved policy in terms of its soft value. Since in practice we prefer policies that are tractable, we will additionally restrict the policy to some set of policies Π, which can correspond, for example, to a parameterized family of distributions such as Gaussians. To account for the constraint that π ∈ Π, we project the improved policy into the desired set of policies. While in principle we could choose any projection, it will turn out to be convenient to use the information projection defined in terms of the KL divergence. In the other words, in the policy improvement step, for each state, we update the policy according to

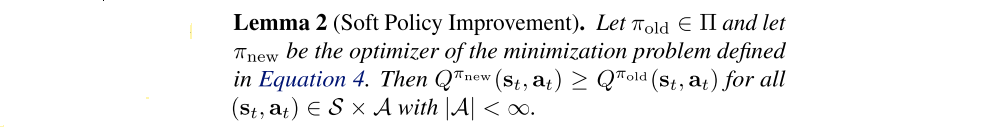

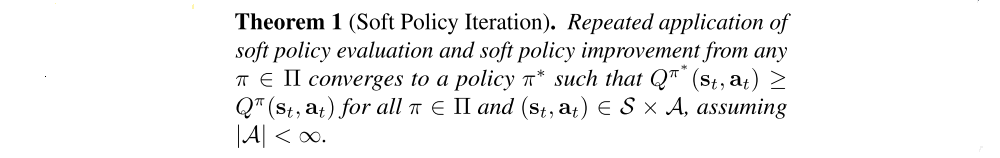

The partition function Z normalizes the distribution, and while it is intractable in general, it does not contribute to the gradient with respect to the new policy and can thus be ignored, as noted in the next section. For this projection, we can show that the new, projected policy has a higher value than the old policy with respect to the objective in Equation 1. We formalize this result in Lemma 2.

The full soft policy iteration algorithm alternates between the soft policy evaluation and the soft policy improvement steps, and it will provably converge to the optimal maximum entropy policy among the policies in Π (Theorem 1). Although this algorithm will provably find the optimal solution, we can perform it in its exact form only in the tabular case. Therefore, we will next approximate the algorithm for continuous domains, where we need to rely on a function approximator to represent the Q-values, and running the two steps until convergence would be computationally too expensive. The approximation gives rise to a new practical algorithm, called soft actor-critic.

4.2 Soft Actor-Critic

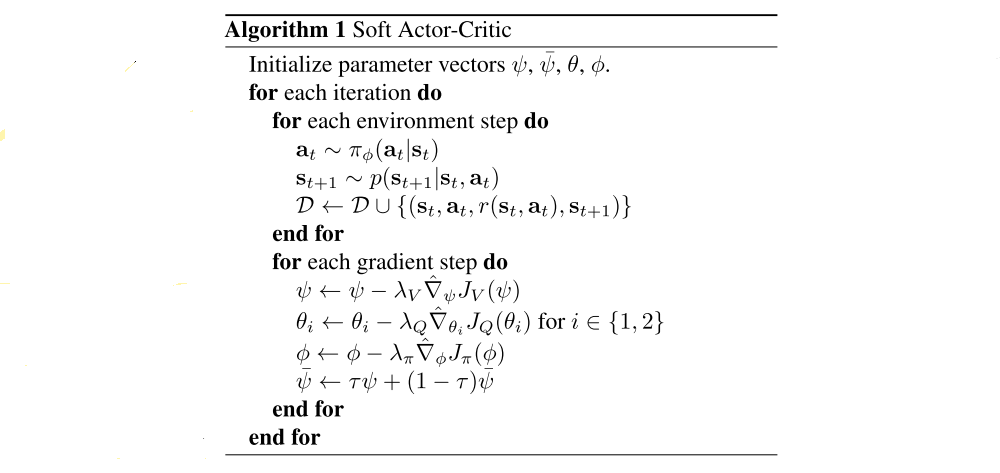

As discussed above, large continuous domains require us to derive a practical approximation to soft policy iteration. To that end, we will use function approximators for both the Q-function and the policy, and instead of running evaluation and improvement to convergence, alternate between optimizing both networks with stochastic gradient descent. We will consider a parameterized state value function Vψ(st), soft Q-function Qθ(st, at), and a tractable policy πφ(at|st). The parameters of these networks are ψ, θ, and φ. For example, the value functions can be modeled as expressive neural networks, and the policy as a Gaussian with mean and covariance given by neural networks. We will next derive update rules for these parameter vectors.

The state value function approximates the soft value. There is no need in principle to include a separate function approximator for the state value, since it is related to the Q-function and policy according to Equation 3. This quantity can be estimated from a single action sample from the current policy without introducing a bias, but in practice, including a separate function approximator for the soft value can stabilize training and is convenient to train simultaneously with the other networks. The soft value function is trained to minimize the squared residual error

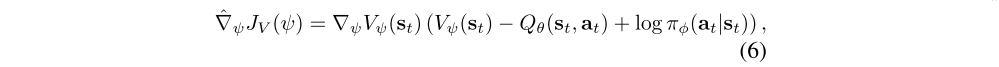

where D is the distribution of previously sampled states and actions, or a replay buffer. The gradient of Equation 5 can be estimated with an unbiased estimator

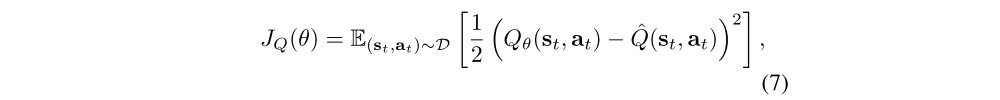

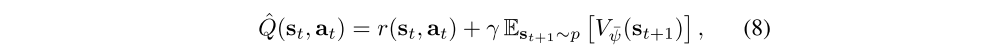

where the actions are sampled according to the current policy, instead of the replay buffer. The soft Q-function parameters can be trained to minimize the soft Bellman residual

with

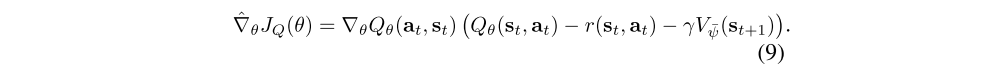

which again can be optimized with stochastic gradients

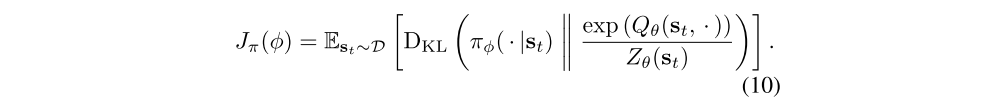

The update makes use of a target value network V¯ψ. Finally, the policy parameters can be learned by directly minimizing the expected KL-divergence in Equation 4:

There are several options for minimizing Jπ. A typical solution for policy gradient methods is to use the likelihood ratio gradient estimator, which does not require backpropagating the gradient through the policy and the target density networks. However, in our case, the target density is the Q-function, which is represented by a neural network an can be differentiated, and it is thus convenient to apply the reparameterization trick instead, resulting in a lower variance estimator. To that end, we reparameterize the policy using a neural network transformation

where εt is an input noise vector, sampled from some fixed distribution, such as a spherical Gaussian. We can now rewrite the objective in Equation 10 as

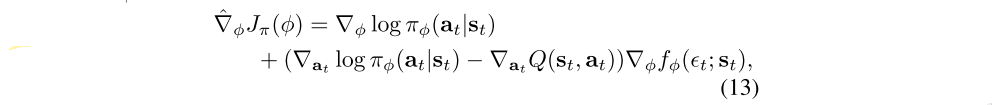

where πφ is defined implicitly in terms of fφ, and we have noted that the partition function is independent of φ and can thus be omitted. We can approximate the gradient of Equation 12 with

where at is evaluated at fφ(εt; st).

Our algorithm also makes use of two Q-functions to mitigate positive bias in the policy improvement step that is known to degrade performance of value based methods. In particular, we parameterize two Q-functions, with parameters θi, and train them independently to optimize JQ(θi). We then use the minimum of the Q-functions for the value gradient in Equation 6 and policy gradient in Equation 13. we found two Q-functions significantly speed up training, especially on harder tasks.

The method alternates between collecting experience from the environment with the current policy and updating the function approximators using the stochastic gradients from batches sampled from a replay buffer. In practice, we take a single environment step followed by one or several gradient steps. Using off-policy data from a replay buffer is feasible because both value estimators and the policy can be trained entirely on off-policy data. The algorithm is agnostic to the parameterization of the policy, as long as it can be evaluated for any arbitrary state-action tuple.

The complete algorithm is described as below