Paper 18: Recurrent Experience Replay in Distributed Reinforcement Learning (R2D2)

Abstract

-

In this paper we investigate the training of RNN-based RL agents from distributed prioritized experience replay.

-

We study the effects of parameter lag resulting in representational drift and recurrent state staleness(老化)and empirically derive an improved training strategy.

-

Using a single network architecture and fixed set of hyper- parameters, the resulting agent, Recurrent Replay Distributed DQN, quadruples(四倍)the previous state of the art.

1 Introduction

The earliest of successes in RL leveraged experience replay for data efficiency and stacked a fixed number of consecutive frames to overcome the partial observability in Atari 2600 games. However, with progress towards increasingly difficult, partially observable domains, the need for more advanced memory-based representations increases, necessitating more principled solutions such as RNNs. The use of LSTMs within RL has been widely adopted to overcome partial observability.

In this paper we investigate the training of RNNs with experience replay. We have three primary contributions.

-

First, we demonstrate the effect of experience replay on parameter lag, leading to representational drift and recurrent state staleness. This is potentially exacerbated(加重)in the distributed training setting, and ultimately results in diminished training stability and performance.

-

Second, we perform an empirical study into the effects of several approaches to RNN training with experience replay, mitigating(减轻)the aforementioned effects.

-

Third, we present an agent that integrates these findings to achieve significant advances in the state of the art on Atari-57 and matches the state of the art on DMLab-30.

2 Background

2.1 Reinforcement Learning

We model the environment as a Partially Observable Markov Decision Process (POMDP) given the tuple (S, A, T, R, Ω, O). Ω gives the set of observations potentially received by the agent and O is the observation function mapping (unobserved) states to probability distributions over observations.

Within this framework, the agent receives an observation o ∈ Ω, which may only contain partial information about the underlying state s ∈ S. When the agent takes an action a ∈ A the environment responds by transitioning to state s’ ∼ T(·|s, a) and giving the agent a new observation o’ ∼ Ω(·|s’) and reward r ∼ R(s, a).

Although there are many approaches to RL in POMDPs, we focus on using RNNs with backpropagation through time (BPTT) to learn a representation that disambiguates(消除歧义)the true state of the POMDP.

DQN training a CNN to represent a value function with Q-learning, from data continuously collected in a replay buffer. A3C uses an LSTM and are trained directly on the online stream of experience without using a replay buffer. DQN and LSTM can be combined.

2.2 Distributed Reinforcement Learning

Recent advances in reinforcement learning have achieved significantly improved performance by leveraging distributed training architectures which separate learning from acting, collecting data from many actors running in parallel on separate environment instances.

2.3 The Recurrent Replay Distributed DQN Agent

We propose a new agent, the Recurrent Replay Distributed DQN (R2D2), and use it to study the interplay(相互作用)between recurrent state, experience replay, and distributed training. R2D2 is most similar to Ape-X, built upon prioritized distributed replay and n-step double Q-learning (with n = 5), generating experience by a large number of actors (typically 256) and learning from batches of replayed experience by a single learner. Like Ape-X, we use the dueling network architecture, but provide an LSTM layer after the convolutional stack.

Instead of regular (s, a, r, s’) transition tuples, we store fixed-length (m = 80) sequences of (s, a, r) in replay, with adjacent(邻近的)sequences overlapping each other by 40 time steps, and never crossing episode boundaries. When training, we unroll both online and target networks on the same sequence of states to generate value estimates and targets. We leave details of our exact treatment of recurrent states in replay for the next sections.

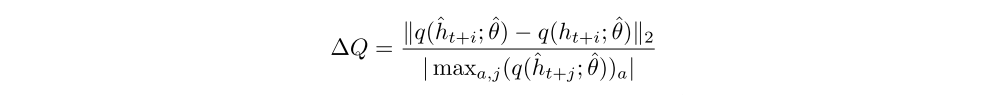

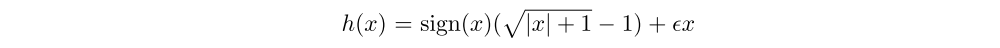

We do not clip rewards, but instead use an invertible(可逆的)value function rescaling of the form

which results in the following n-step targets for the Q-value function:

Here, θ− denotes the target network parameters which are copied from the online network parameters θ every 2500 learner steps.

Our replay prioritization differs from that of Ape-X in that we use a mixture of max and mean priority exponent to 0.9. This more aggressive scheme is motivated by our observation that averaging absolute n-step TD-errors δi over the sequence: p = η maxi δi + (1 − η)¯δ. We set η and the over long sequences tends to wash out large errors, thereby compressing the range of priorities and limiting the ability of prioritization to pick out useful experience.

Finally, we used the discount of γ = 0.997, and disabled the loss-of-life-as-episode-end heuristic that has been used in Atari agents in some of the work. A full list of hyper-parameters is provided in the Appendix.

We train the R2D2 agent with a single GPU-based learner, performing approximately 5 network updates per second (each update on a mini-batch of 64 length-80 sequences), and each actor performing ∼ 260 environment steps per second on Atari (∼ 130 per second on DMLab).

3 Training Recurrent RL Agents with Experience Replay

In order to achieve good performance in a partially observed environment, an RL agent requires a state representation that encodes information about its state-action trajectory in addition to its current observation. The most common way to achieve this is by using an RNN, typically an LSTM as part of the agent’s state encoding. To train an RNN from replay and enable it to learn meaningful long-term dependencies, whole state-action trajectories need to be stored in replay and used for training the network. DRQN compared two strategies of training an LSTM from replayed experience:

-

Using a zero start state to initialize the network at the beginning of sampled sequences.

The zero start state strategy’s appeal lies in its simplicity, and it allows independent decorrelated sampling of relatively short sequences, which is important for robust optimization of a neural network. On the other hand, it forces the RNN to learn to recover meaningful predictions from an atypical(非典型的)initial recurrent state (‘initial recurrent state mismatch’), which may limit its ability to fully rely on its recurrent state and learn to exploit long temporal correlations.

-

Replaying whole episode trajectories.

The second strategy avoids the problem of finding a suitable initial state, but creates a number of practical, computational, and algorithmic issues due to varying and potentially environment-dependent sequence length, and higher variance of network updates because of the highly correlated nature of states in a trajectory when compared to training on randomly sampled batches of experience tuples.

In DRQN, the difference between the two strategies for empirical agent performance on a set of Atari games is little, and therefore opted for the simpler zero start state strategy.

But in R2D2, to fix these issues, we propose and evaluate two strategies for training a RNN from randomly sampled replay sequences, that can be used individually or in combination:

-

Stored state: Storing the recurrent state in replay and using it to initialize the network at training time. This partially remedies the weakness of the zero start state strategy, however it may suffer from the effect of ‘representational drift’ leading to ‘recurrent state staleness’, as the stored recurrent state generated by a sufficiently old network could differ significantly from a typical state produced by a more recent version.

-

Burn-in: Allow the network a ‘bsurn-in period’ by using a portion of the replay sequence only for unrolling the network and producing a start state, and update the network only on the remaining part of the sequence. We hypothesize that this allows the network to partially recover from a poor start state (zero, or stored but stale) and find itself in a better initial state before being required to produce accurate outputs.

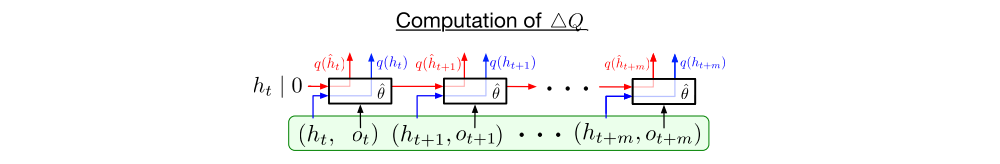

In all our experiments we will be using the proposed agent architecture from Section 2.3 with replay sequences of length m = 80, with an optional burn-in prefix of l = 40 or 20 steps. Our aim is to assess the negative effects of representational drift and recurrent state staleness on network training and how they are mitigated by the different training strategies. For that, we will compare the Q-values produced by the network on sampled replay sequences when unrolled using one of these strategies and the Q-values produced when using the true stored recurrent states at each step (see the following figure, showing different sources for the hidden state).

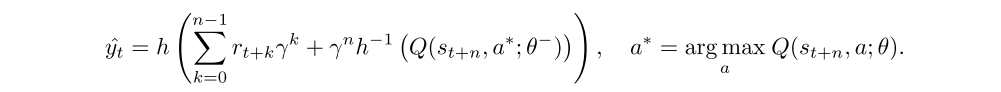

More formally, let ot, . . . , ot+m and ht, . . . , ht+m denote the replay sequence of observations and stored recurrent states, and denote by ht+1 = h(ot, ht; θ) and q(ht; θ) the recurrent state and Q-value vector output by the recurrent neural network with parameter vector θ, respectively. We write hˆt for the hidden state, used during training and initialized under one of the above strategies (either hˆt = 0 or ˆht = ht). Then ˆht+i = h(ot+i−1, ˆht+i−1; ˆθ) is computed by unrolling the network with parameters ˆθ on the sequence ot, . . . , ot+l+m−1.

We estimate the impact of representational drift and recurrent state staleness by their effect on the Q-value estimates, by measuring Q-value discrepancy