Paper 20: Making Efficient Use of Demonstrations to Solve Hard Exploration Problems (R2D3)

Abstract

-

This paper introduces R2D3, an agent that makes efficient use of demonstrations to solve hard exploration problems in partially observable environments with highly variable initial conditions.

-

We also introduce a suite of eight tasks that combine these three properties, and show that R2D3 can solve several of the tasks where other state of the art methods (both with and without demonstrations) fail to see even a single successful trajectory after tens of billions of steps of exploration.

1 Introduction

Reinforcement learning from demonstrations has proven to be an effective strategy for attacking problems that require sample efficiency and involve hard exploration.

In this paper, we attack the problem of learning from demonstrations in hard exploration tasks in partially observable environments with highly variable initial conditions. These three aspects together conspire to make learning challenging:

-

Sparse rewardsinduce a difficult exploration problem, which is a challenge for many state of the art RL methods. An environment has sparse reward when a non-zero reward is only seen after taking a long sequence of correct actions. Our approach is able to solve tasks where standard methods run for billions of steps without seeing a single non-zero reward. -

Partial observabilityforces the use of memory, and also reduces the generality(大部分)of information provided by a single demonstration, since trajectories cannot be broken into isolated transitions using the Markov property. An environment has partial observability if the agent can only observe a part of the environment at each time-step. -

Highly variable initial conditions(i.e. changes in the starting configuration of the environment in each episode) are a big challenge for learning from demonstrations, because the demonstrations can not account for all possible configurations. When the initial conditions are fixed it is possible to be extremely efficient through tracking; however, with a large variety of initial conditions the agent is forced to generalize over environment configurations. Generalizing between different initial conditions is known to be difficult.

Our approach to these problems combines demonstrations with off-policy, recurrent Q-learning in a way that allows us to make very efficient use of the available data. In particular, we vastly outperform behavioral cloning using the same set of demonstrations in all of our experiments.

Another desirable property of our approach is that our agents are able to learn to outperform the demonstrators, and in some cases even to discover strategies that the demonstrators were not aware of. In one of our tasks the agent is able to discover and exploit a bug in the environment in spite of all the demonstrators completing the task in the intended way.

Learning from a small number of demonstrations under highly variable initial conditions is not straightforward. We identify a key parameter of our algorithm, the demo-ratio, which controls the proportion of expert demonstrations vs agent experience in each training batch. This hyper-parameter has a dramatic effect on the performance of the algorithm. Surprisingly, we find that the optimal demo ratio is very small (but non-zero) across a wide variety of tasks.

The mechanism our agents use to efficiently extract information from expert demonstrations is to use them in a way that guides (or biases) the agent’s own autonomous exploration of the environment. Although this mechanism is not obvious from the algorithm construction, our behavioral analysis confirms the presence of this guided exploration effect.

The main contributions of this paper are,

-

We design a new agent that makes efficient use of demonstrations to solve sparse reward tasks in partially observed environments with highly variable initial conditions.

-

We provide an analysis of the mechanism our agents use to exploit information from the demonstrations.

-

We introduce a suite of eight tasks that support this line of research.

2 Recurrent Replay Distributed DQN from Demonstrations

We propose a new agent, which we refer to as Recurrent Replay Distributed DQN from Demonstrations (R2D3). R2D3 is designed to make efficient use of demonstrations to solve sparse reward tasks in partially observed environments with highly variable initial conditions. This section just gives an overview of the agent.

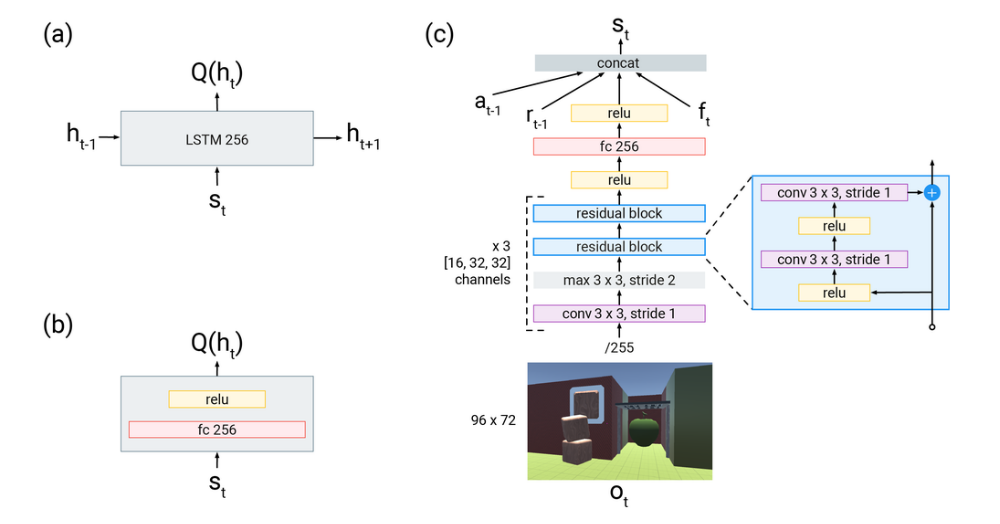

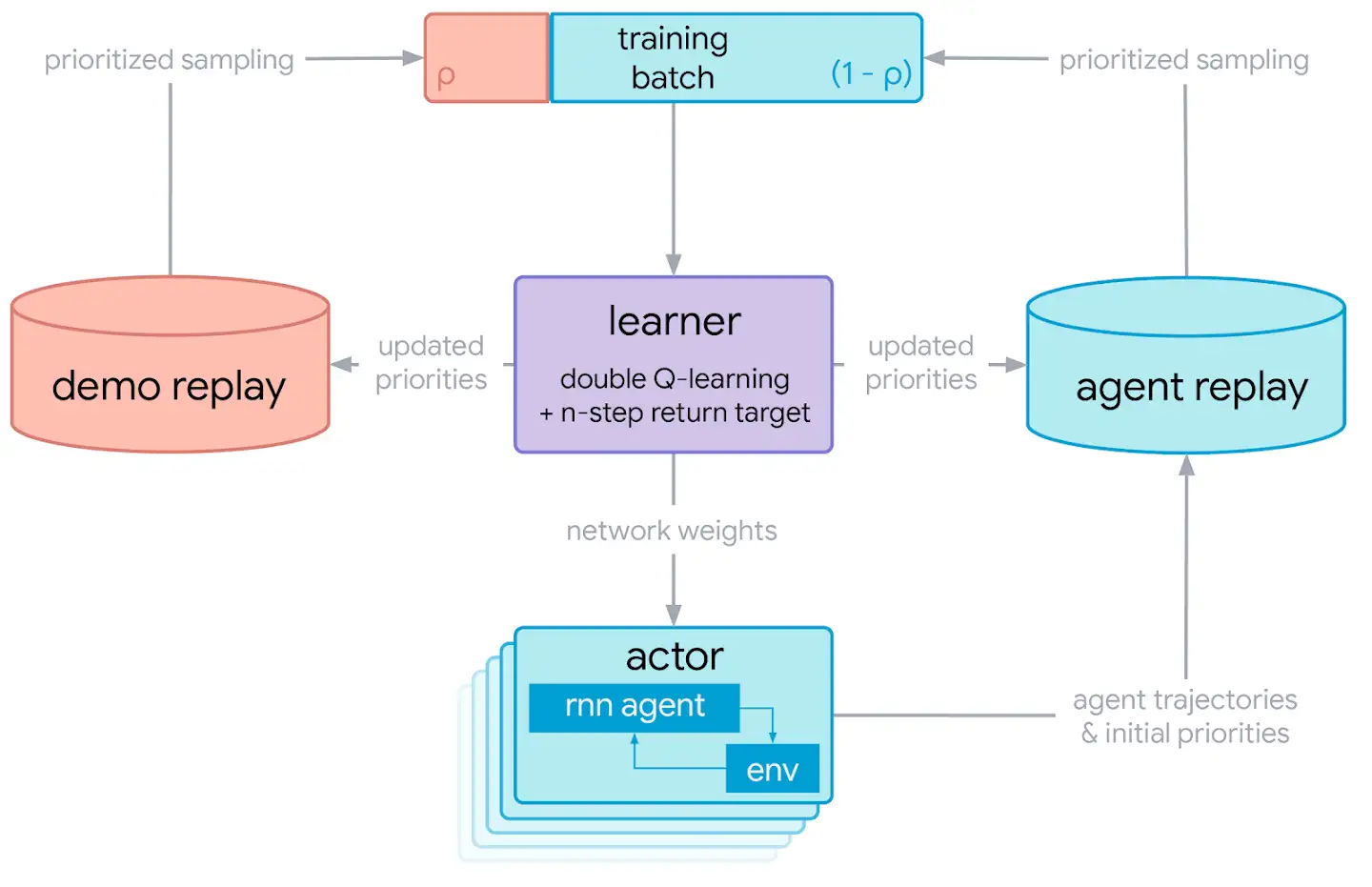

The R2D3 distributed system diagram

The architecture of the R2D3 agent is shown in the figure above. There are several actor processes, each running independent copies of the behavior against an instance of the environment. Each actor streams its experience to a shared agent replay buffer, where experience from all actors is aggregated and globally prioritized using a mixture of max and mean of the TD-errors with priority exponent η=1.0 as in R2D2. The actors periodically request the latest network weights from the learner process in order to update their behavior.

In addition to the agent replay, we maintain a second demo replay buffer, which is populated with expert demonstrations of the task to be solved. Expert trajectories are also prioritized using the scheme of R2D2. Maintaining separate replay buffers for agent experience and expert demonstrations allows us to prioritize the sampling of agent and expert data separately.

The learner process samples batches of data from both the agent and demo replay buffers simultaneously. A hyper-parameter ρ, the demo ratio, controls the proportion of data coming from expert demonstrations versus from the agent’s own experience. The demo ratio is implemented at a batch level by randomly choosing whether to sample from the expert replay buffer independently for each element with probability ρ. Using a stochastic demo ratio in this way allows us to target demo ratios that are smaller than the batch size, which we found to be very important for good performance. The objective optimized by the learner uses of n-step, double Q-learning (with n=5) and a dueling architecture. In addition to performing network updates, the learner is also responsible for pushing updated priorities back to the replay buffers.

In each replay buffer, we store fixed-length (m = 80) sequences of (s,a,r) tuples where adjacent sequences overlap by 40 time-steps. The sequences never cross episode boundaries. Given a single batch of trajectories we unroll both online and target networks on the same sequence of states to generate value estimates with the recurrent state initialized to zero. Proper initialization of the recurrent state would require always replaying episodes from the beginning, which would add significant complexity to our implementation. As an approximation of this we treat the first 40 steps of each sequence as a burn-in phase, and apply the training objective to the final 40 steps only. An alternative approximation would be to store stale recurrent states in replay, but we did not find this to improve performance over zero initialization with burn-in. (just as in R2D2)

3 Background

Exploration remains one of the most fundamental challenges for reinforcement learning. So-called “hard-exploration” domains are those in which rewards are sparse, and optimal solutions typically have long and sparsely-rewarded trajectories. Hard-exploration domains may also have many distracting dead ends that the agent may not be able to recover from once it gets into a certain state. In recent years, the most notable such domains are Atari environments, including Montezuma’s Revenge and Pitfall. These domains are particularly tricky for classical RL algorithms because even finding a single non-zero reward to bootstrap from is incredibly challenging.

A common technique used to address the difficulty of exploration is to encourage the agent to visit under-explored areas of the state-space. Such techniques are commonly known as intrinsic motivation or count-based exploration. However, these approaches do not scale well as the state space grows, as they still require exhaustive search in sparse reward environments. Additionally, recent empirical results suggest that these methods do not consistently outperform ϵ-greedy exploration. The difficulty of exploration is also a consequence of the current inability of our agents to abstract the world and learn scalable, causal models with explanatory power. Instead they often use low-level features or handcrafted heuristics and lack the generalization power necessary to work in a more abstract space. Hints can be provided to the agent which bias it towards promising regions of the state space either via reward-shaping or by introducing a sequence of curriculum(课程) tasks. However, these approaches can be difficult to specify and, in the case of reward shaping, often lead to unexpected behavior where the agent learns to exploit the modified rewards.

Another hallmark of hard-exploration benchmarks is that they tend to be fully-observable and exhibit little variation between episodes. Nevertheless, techniques like random no-ops and “sticky actions” have been proposed to artificially increase episode variance in Atari, an alternative is to instead consider domains with inherent variability. Other recent work on the Obstacle Tower challenge domain is similar to our task suite in this regard. Reliance on determinism of the environment is one of the chief criticisms of imitation. In contrast, our approach is able to solve tasks with substantial per-episode variability.

GAIL is another imitation learning method, however GAIL has never been successfully applied to complex partially observable environments that require memory.

4 Hard-Eight Task Suite

To address the difficulty of hard exploration in partially observable problems with highly variable initital conditions we introduce a collection of eight tasks, which exhibit these properties. Due to the generated nature of these tasks and the rich form of interaction between the agent and environment, we see greatly increased levels of variability between episodes. From the perspective of the learning process, these tasks are particularly interesting because just memorizing an open loop sequence of actions is unlikely to achieve even partial success on a new episode. The nature of interaction with the environment combined with a limited field of view also necessitates the use of memory in the agent.

5 Baselines

In this section we discuss the baselines and ablations we use to compare against our R2D3 agent in the experiments. We compare to Behavior Cloning (a common baseline for learning from demonstrations) as well as two ablations of our method which individually remove either recurrence or demonstrations from R2D3.