Paper 23: Ray: A Distributed Framework for Emerging AI Applications

Github: https://github.com/ray-project/ray.

Docs: https://docs.ray.io/en/latest/rllib.html.

Abstract

-

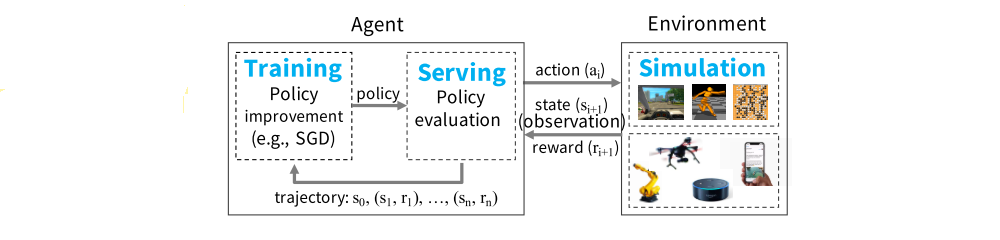

The next generation of AI applications will continuously interact with the environment and learn from these inter- actions. These applications impose(强加)new and demanding systems requirements, both in terms of performance and flexibility.

-

In this paper, we consider these requirements and present Ray - a distributed system to address them.

-

Ray implements a unified interface that can express both task-parallel and actor-based computations, supported by a single dynamic execution engine. To meet the performance requirements, Ray employs a distributed scheduler(调度)and a distributed and fault-tolerant store to manage the system’s control state.

1 Introduction

Finding effective policies in large-scale applications requires three main capabilities.

-

First, RL methods often rely on simulation to evaluate policies. Simulations make it possible to explore many different choices of action sequences and to learn about the long-term consequences of those choices.

-

Second, like their supervised learning counterparts(同行), RL algorithms need to perform distributed training to improve the policy based on data generated through simulations or interactions with the physical environment.

-

Third, policies are intended to provide solutions to control problems, and thus it is necessary to serve the policy in interactive closed-loop and open-loop control scenarios.

These characteristics drive new systems requirements: a system for RL must support fine-grained computations (e.g., rendering actions in milliseconds when interacting with the real world, and performing vast numbers of simulations), must support heterogeneity(异质性)both in time (e.g., a simulation may take milliseconds or hours) and in resource usage (e.g., GPUs for training and CPUs for simulations), and must support dynamic execution, as results of simulations or interactions with the environment can change future computations. Thus, we need a dynamic computation framework that handles millions of heterogeneous tasks per second at millisecond-level latencies.

In this paper, we propose Ray, a general-purpose cluster-computing framework that enables simulation, training, and serving for RL applications. The requirements of these workloads range from lightweight and stateless computations, such as for simulation, to long-running and stateful computations, such as for training. To satisfy these requirements, Ray implements a unified interface that can express both task-parallel and actor-based computations. Tasks enable Ray to efficiently and dynamically load balance simulations, process large inputs and state spaces (e.g., images, video), and recover from failures. In contrast, actors enable Ray to efficiently support stateful computations, such as model training, and expose shared mutable state to clients, (e.g., a parameter server). Ray implements the actor and the task abstractions on top of a single dynamic execution engine that is highly scalable and fault tolerant.

To meet the performance requirements, Ray distributes two components that are typically centralized in existing frameworks: (1) the task scheduler and (2) a metadata store which maintains the computation lineage and a directory for data objects. This allows Ray to schedule millions of tasks per second with millisecond-level latencies. Furthermore, Ray provides lineage-based fault tolerance for tasks and actors, and replication-based fault tolerance for the metadata store.

We make the following contributions;

-

We design and build the first distributed framework that unifies training, simulation, and serving - necessary components of emerging RL applications.

-

To support these workloads, we unify the actor and task-parallel abstractions on top of a dynamic task execution engine.

-

To achieve scalability and fault tolerance, we propose a system design principle in which control state is stored in a shared metadata store and all other system components are stateless.

-

To achieve scalability, we propose a bottom-up distributed scheduling strategy.

2 Motivation and Requirements

A framework for RL applications must provide efficient support for training, serving, and simulation. Next, we briefly describe these workloads.

Example of an RL system

Training typically involves running SGD, often in a distributed setting, to update the policy. Distributed SGD typically relies on an allreduce aggregation step or a parameter server.

Serving uses the trained policy to render an action based on the current state of the environment. A serving system aims to minimize latency, and maximize the number of decisions per second. To scale, load is typically balanced across multiple nodes serving the policy.

Finally, most existing RL applications use simulations to evaluate the policy - current RL algorithms are not sample-efficient enough to rely solely on data obtained from interactions with the physical world. These simulations vary widely in complexity. They might take a few ms (e.g., simulate a move in a chess game) to minutes (e.g., simulate a realistic environment for a self-driving car).

In contrast with supervised learning, in which training and serving can be handled separately by different systems, in RL all three of these workloads are tightly coupled in a single application, with stringent(严格的)latency requirements between them. Currently, no framework supports this coupling of workloads. In theory, multiple specialized frameworks could be stitched together to provide the overall capabilities, but in practice, the resulting data movement and latency between systems is prohibitive in the context of RL. As a result, researchers and practitioners have been building their own one-off systems.

This state of affairs calls for the development of new distributed frameworks for RL that can efficiently support training, serving, and simulation. In particular, such a framework should satisfy the following requirements:

-

Fine-grained, heterogeneous computations. The duration of a computation can range from milliseconds (e.g., taking an action) to hours (e.g., training a complex policy). Additionally, training often requires heterogeneous hardware (e.g., CPUs, GPUs, or TPUs).

-

Flexible computation model. RL applications require both stateless and stateful computations. Stateless computations can be executed on any node in the system, which makes it easy to achieve load balancing and movement of computation to data, if needed. Thus stateless computations are a good fit for fine-grained simulation and data processing, such as extracting features from images or videos. In contrast stateful computations are a good fit for implementing parameter servers, performing repeated computation on GPU-backed data, or running third-party simulators that do not expose their state.

-

Dynamic execution. Several components of RL applications require dynamic execution, as the order in which computations finish is not always known in advance (e.g., the order in which simulations finish), and the results of a computation can determine future computations (e.g., the results of a simulation will determine whether we need to perform more simulations).

3 Programming and Computation Model

Ray implements a dynamic task graph computation model, i.e., it models an application as a graph of dependent tasks that evolves during execution. On top of this model, Ray provides both an actor and a task-parallel programming abstraction.

3.1 Programming Model

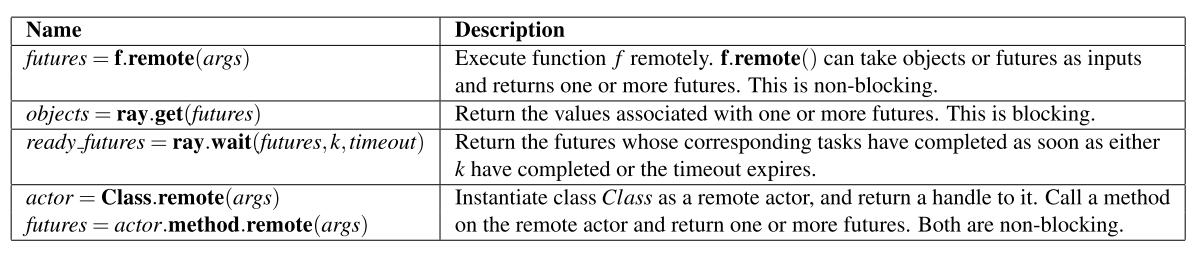

Tasks. A task represents the execution of a remote function on a stateless worker. When a remote function is invoked, a future representing the result of the task is returned immediately. Futures can be retrieved using ray.get() and passed as arguments into other remote functions without waiting for their result. This allows the user to express parallelism while capturing data dependencies.

Ray API

Remote functions operate on immutable objects and are expected to be stateless and side-effect free: their outputs are determined solely by their inputs. This implies idempotence(幂等性), which simplifies fault tolerance through function re-execution on failure.

Actors. An actor represents a stateful computation. Each actor exposes methods that can be invoked remotely and are executed serially. A method execution is similar to a task, in that it executes remotely and returns a future, but differs in that it executes on a stateful worker. A handle to an actor can be passed to other actors or tasks, making it possible for them to invoke methods on that actor.

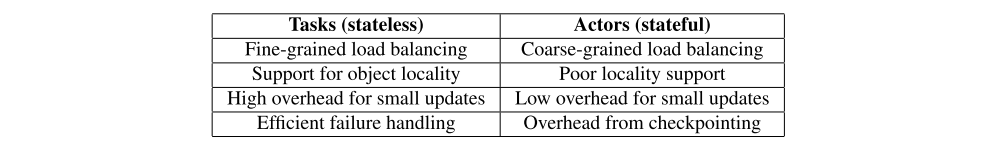

Tasks vs. actors tradeoffs

The figure above summarizes the properties of tasks and actors. Tasks enable fine-grained load balancing through leveraging load-aware scheduling at task granularity, input data locality, as each task can be scheduled on the node storing its inputs, and low recovery overhead, as there is no need to checkpoint and recover intermediate state. In contrast, actors provide much more efficient fine-grained updates, as these updates are performed on internal rather than external state, which typically requires serialization and deserialization. For example, actors can be used to implement parameter servers and GPU-based iterative computations (e.g., training). In addition, actors can be used to wrap third-party simulators and other opaque handles that are hard to serialize.

To satisfy the requirements for heterogeneity and flexibility, we augment the API in three ways.

-

First, to handle concurrent tasks with heterogeneous durations, we introduce ray.wait(), which waits for the first k available results, instead of waiting for all results like ray.get().

-

Second, to handle resource-heterogeneous tasks, we enable developers to specify resource requirements so that the Ray scheduler can efficiently manage resources.

-

Third, to improve flexibility, we enable nested(嵌套的)remote functions, meaning that remote functions can invoke other remote functions. This is also critical for achieving high scalability, as it enables multiple processes to invoke remote functions in a distributed fashion.

3.2 Computation Model

Ray employs a dynamic task graph computation model, in which the execution of both remote functions and actor methods is automatically triggered by the system when their inputs become available. In this section, we describe how the computation graph is constructed from a user program. The following is the python code implementing learning a policy in Ray:

@ray.remote

def create_policy():

# Initialize the policy randomly.

return policy

@ray.remote(num_gpus=1)

class Simulator(object):

def __init__(self):

# Initialize the environment.

self.env = Environment()

def rollout(self, policy, num_steps):

observations = []

observation = self.env.current_state()

for _ in range(num_steps):

action = policy(observation)

observation = self.env.step(action)

observations.append(observation)

return observations

@ray.remote(num_gpus=2)

def update_policy(policy, *rollouts):

# Update the policy.

return policy

@ray.remote

def train_policy():

# Create a policy.

policy_id = create_policy.remote()

# Create 10 actors.

simulators = [Simulator.remote() for _ in range(10)]

# Do 100 steps of training.

for _ in range(100):

# Perform one rollout on each actor.

rollout_ids = [s.rollout.remote(policy_id) for s in simulators]

# Update the policy with the rollouts.

policy_id = update_policy.remote(policy_id, *rollout_ids)

return ray.get(policy_id)

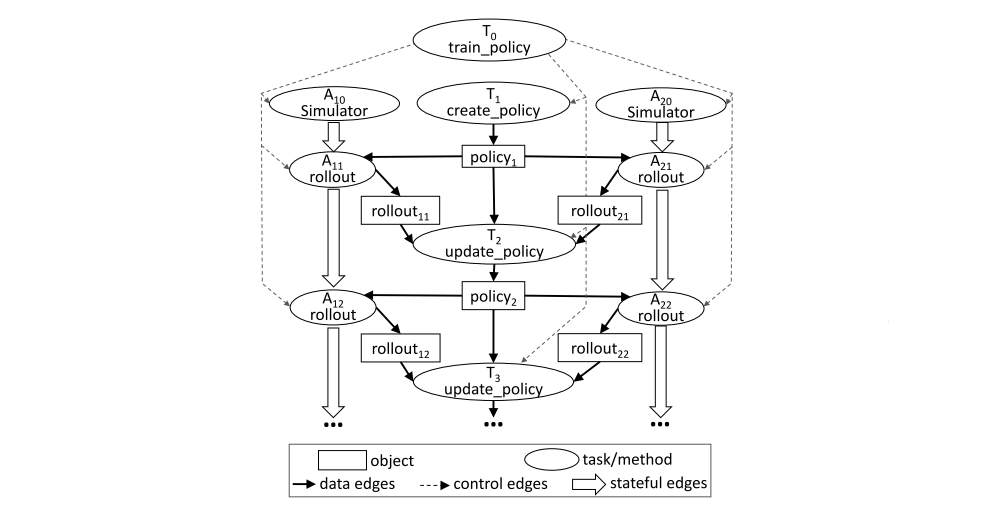

Ignoring actors first, there are two types of nodes in a computation graph: data objects and remote function invocations, or tasks. There are also two types of edges: data edges and control edges. Data edges capture the dependencies between data objects and tasks. More precisely, if data object D is an output of task T, we add a data edge from T to D. Similarly, if D is an input to T, we add a data edge from D to T. Control edges capture the computation dependencies that result from nested remote functions: if task T1 invokes task T2, then we add a control edge from T1 to T2.

Actor method invocations are also represented as nodes in the computation graph. They are identical to tasks with one key difference. To capture the state dependency across subsequent method invocations on the same actor, we add a third type of edge: a stateful edge. If method Mj is called right after method Mi on the same actor, then we add a stateful edge from Mi to Mj. Thus, all methods invoked on the same actor object form a chain that is connected by stateful edges. This chain captures the order in which these methods were invoked.

Stateful edges help us embed actors in an otherwise stateless task graph, as they capture the implicit data dependency between successive method invocations sharing the internal state of an actor. Stateful edges also enable us to maintain lineage. As in other dataflow systems, we track data lineage to enable reconstruction. By explicitly including stateful edges in the lineage graph, we can easily reconstruct lost data, whether produced by remote functions or actor methods.

The task graph corresponding to an invocation of train_policy.remote()

Remote function calls and the actor method calls correspond to tasks in the task graph. The figure shows two actors. The method invocations for each actor (the tasks labeled A1i and A2i) have stateful edges between them indicating that they share the mutable(可变的)actor state. There are control edges from train policy to the tasks that it invokes. To train multiple policies in parallel, we could call train policy.remote() multiple times.

4 Architecture

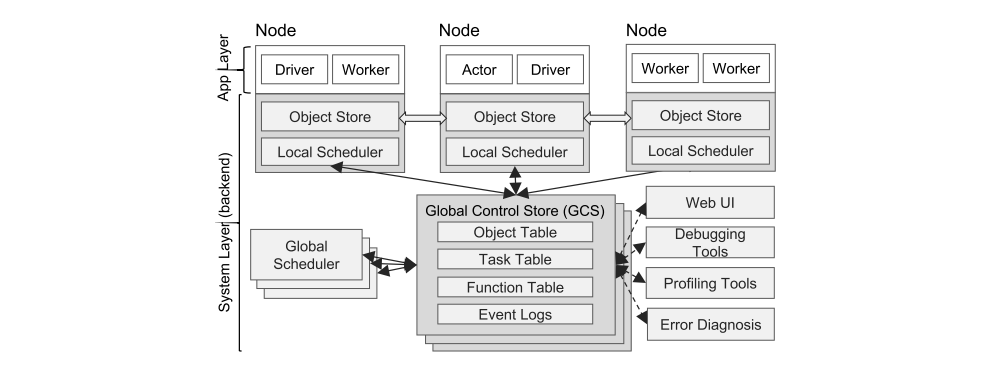

Ray’s architecture comprises (1) an application layer implementing the API, and (2) a system layer providing high scalability and fault tolerance. The application layer implements the API and the computation model described in Section 3, the system layer implements task scheduling and data management to satisfy the performance and fault-tolerance requirements.

Ray’s architecture

4.1 Application Layer

The application layer consists of three types of processes:

-

Driver: A process executing the user program.

-

Worker: A stateless process that executes tasks (remote functions) invoked by a driver or another worker. Workers are started automatically and assigned tasks by the system layer. When a remote function is declared, the function is automatically published to all workers. A worker executes tasks serially, with no local state maintained across tasks.

-

Actor: A stateful process that executes, when invoked, only the methods it exposes. Unlike a worker, an actor is explicitly instantiated by a worker or a driver. Like workers, actors execute methods serially, except that each method depends on the state resulting from the previous method execution.

4.2 System Layer

The system layer consists of three major components: a global control store, a distributed scheduler, and a distributed object store. All components are horizontally scalable and fault-tolerant.

4.2.1 Global Control Store (GCS)

The global control store (GCS) maintains the entire control state of the system, and it is a unique feature of our design. At its core, GCS is a key-value store with pub-sub(发布订阅)functionality. We use sharding(分片)to achieve scale, and per-shard chain replication to provide fault tolerance. The primary reason for the GCS and its design is to maintain fault tolerance and low latency for a system that can dynamically spawn millions of tasks per second.

Fault tolerance in case of node failure requires a solution to maintain lineage information. Existing lineage-based solutions focus on coarse-grained parallelism and can therefore use a single node (e.g., master, driver) to store the lineage without impacting performance. However, this design is not scalable for a fine- grained and dynamic workload like simulation. Therefore, we decouple the durable lineage storage from the other system components, allowing each to scale independently.

Maintaining low latency requires minimizing overheads(一般开支)in task scheduling, which involves choosing where to execute, and subsequently task dispatch(派遣), which involves retrieving remote inputs from other nodes. Many existing dataflow systems couple these by storing object locations and sizes in a centralized scheduler, a natural design when the scheduler is not a bottleneck. However, the scale and granularity that Ray targets requires keeping the centralized scheduler off the critical path. Involving the scheduler in each object transfer is prohibitively expensive for primitives important to distributed training like allreduce, which is both communication-intensive and latency-sensitive. Therefore, we store the object metadata in the GCS rather than in the scheduler, fully decoupling task dispatch from task scheduling.

In summary, the GCS significantly simplifies Ray’s overall design, as it enables every component in the system to be stateless. This not only simplifies support for fault tolerance (i.e., on failure, components simply restart and read the lineage from the GCS), but also makes it easy to scale the distributed object store and scheduler independently, as all components share the needed state via the GCS. An added benefit is the easy development of debugging, profiling, and visualization tools.

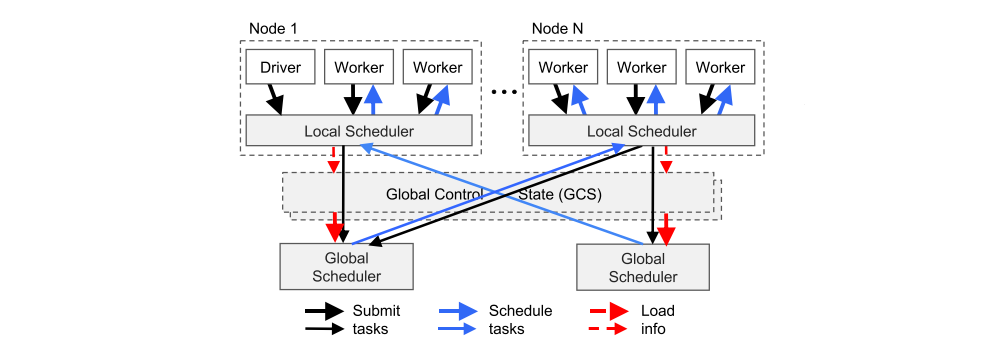

4.2.2 Bottom-Up Distributed Scheduler

Ray needs to dynamically schedule millions of tasks per second, tasks which may take as little as a few milliseconds. None of the cluster schedulers we are aware of meet these requirements.

To satisfy the above requirements, we design a two-level hierarchical scheduler consisting of a global scheduler and per-node local schedulers. To avoid overloading the global scheduler, the tasks created at a node are submitted first to the node’s local scheduler. A local scheduler schedules tasks locally unless the node is overloaded (i.e., its local task queue exceeds a predefined threshold), or it cannot satisfy a task’s requirements (e.g., lacks a GPU). If a local scheduler decides not to schedule a task locally, it forwards it to the global scheduler. Since this scheduler attempts to schedule tasks locally first (i.e., at the leaves of the scheduling hierarchy), we call it a bottom-up scheduler.

Bottom-up distributed scheduler

Tasks are submitted bottom-up, from drivers and workers to a local scheduler and forwarded to the global scheduler only if needed. The thickness of each arrow is proportional to its request rate.

The global scheduler considers each node’s load and task’s constraints to make scheduling decisions. More precisely, the global scheduler identifies the set of nodes that have enough resources of the type requested by the task, and of these nodes selects the node which provides the lowest estimated waiting time. At a given node, this time is the sum of (i) the estimated time the task will be queued at that node (i.e., task queue size times average task execution), and (ii) the estimated transfer time of task’s remote inputs (i.e., total size of remote inputs divided by average bandwidth). The global scheduler gets the queue size at each node and the node resource availability via heartbeats, and the location of the task’s inputs and their sizes from GCS. Furthermore, the global scheduler computes the average task execution and the average transfer bandwidth using simple exponential averaging. If the global scheduler becomes a bottleneck, we can instantiate more replicas all sharing the same information via GCS. This makes our scheduler architecture highly scalable.

4.2.3 In-Memory Distributed Object Store

To minimize task latency, we implement an in-memory distributed storage system to store the inputs and outputs of every task, or stateless computation. On each node, we implement the object store via shared memory. This allows zero-copy data sharing between tasks running on the same node. As a data format, we use Apache Arrow.

If a task’s inputs are not local, the inputs are replicated to the local object store before execution. Also, a task writes its outputs to the local object store. Replication eliminates the potential bottleneck due to hot data objects and minimizes task execution time as a task only reads/writes data from/to the local memory. This increases throughput for computation-bound workloads, a profile shared by many AI applications. For low latency, we keep objects entirely in memory and evict them as needed to disk using an LRU policy.

As with existing cluster computing frameworks, the object store is limited to immutable data. This obviates(消除)the need for complex consistency protocols(协议)(as objects are not updated), and simplifies support for fault tolerance. In the case of node failure, Ray recovers any needed objects through lineage re-execution. The lineage stored in the GCS tracks both stateless tasks and stateful actors during initial execution; we use the former to reconstruct objects in the store.

For simplicity, our object store does not support distributed objects, i.e., each object fits on a single node. Distributed objects like large matrices or trees can be implemented at the application level as collections of futures.

4.2.4 Implementation

The GCS uses one Redis key-value store per shard, with entirely single-key operations. GCS tables are sharded by object and task IDs to scale, and every shard is chain-replicated for fault tolerance. We implement both the local and global schedulers as event-driven, single-threaded processes. Internally, local schedulers maintain cached state for local object metadata, tasks waiting for inputs, and tasks ready for dispatch to a worker. To transfer large objects between different object stores, we stripe the object across multiple TCP connections.

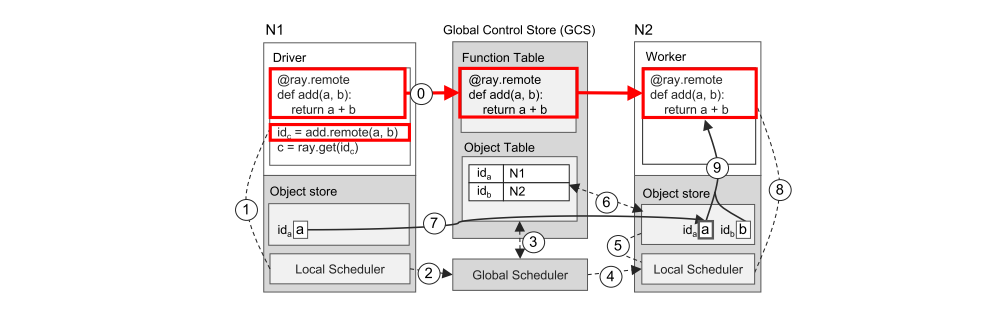

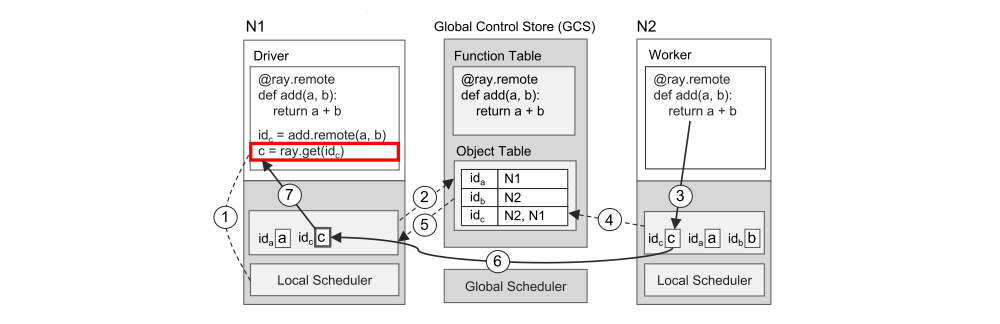

4.3 Putting Everything Together

We have two figures to illustrate how Ray works end-to-end with a simple example that adds two objects a and b, which could be scalars or matrices, and returns result c. The remote function add() is automatically registered with the GCS upon initialization and distributed to every worker in the system.

Executing a task remotely

It shows the step-by-step operations triggered by a driver invoking add.remote(a,b), where a and b are stored on nodes N1 and N2, respectively. The driver submits add(a, b) to the local scheduler (step 1), which forwards it to a global scheduler (step 2). Next, the global scheduler looks up the locations of add(a, b)’s arguments in the GCS (step 3) and decides to schedule the task on node N2, which stores argument b (step 4). The local scheduler at node N2 checks whether the local object store contains add(a, b)’s arguments (step 5). Since the local store doesn’t have object a, it looks up a’s location in the GCS (step 6). Learning that a is stored at N1, N2’s object store replicates it locally (step 7). As all arguments of add() are now stored locally, the local scheduler invokes add() at a local worker (step 8), which accesses the arguments via shared memory (step 9).

Returning the result of a remote task