Paper 24: RLlib: Abstractions for Distributed Reinforcement Learning

Github: https://github.com/ray-project/ray.

Docs: https://docs.ray.io/en/latest/rllib.html.

Abstract

-

RL algorithms involve the deep nesting(嵌套)of highly irregular computation patterns, each of which typically exhibits opportunities for distributed computation.

-

We argue for distributing RL components in a composable way by adapting algorithms for top-down hierarchical control, thereby encapsulating(封装)parallelism and resource requirements within short-running compute tasks.

-

We demonstrate the benefits of this principle through RLlib: a library that provides scalable software primitives for RL. These primitives enable a broad range of algorithms to be implemented with high performance, scalability, and substantial code reuse.

1 Introduction

There’s a fundamental need for composable parallel primitives to support research in RL.

We believe that the ability to build scalable RL algorithms by composing and reusing existing components and implementations is essential for the rapid development and progress of the field. We argue for structuring distributed RL components around the principles of logically centralized program control and parallelism encapsulation. We built RLlib using these principles, and as a result were not only able to implement a broad range of state-of-the-art RL algorithms, but also to pull out scalable primitives that can be used to easily compose new algorithms.

1.1 Irregularity of RL training workloads

Modern RL algorithms are highly irregular in the computation patterns they create, pushing the boundaries of computation models supported by popular distribution frameworks. This irregularity occurs at several levels:

-

The duration and resource requirements of tasks differ by orders of magnitude depending on the algorithm;

-

Communication patterns vary, from synchronous to asynchronous gradient-based optimization, to having several types of asynchronous tasks in high-throughput off-policy algorithms such as Ape-X and IMPALA;

-

Nested computations are generated by model-based hybrid algorithms, hyperparameter tuning in conjunction with RL or DL training, or the combination of derivative-free and gradient-based optimization within a single algorithm.

-

RL algorithms often need to maintain and update substantial amounts of state including policy parameters, replay buffers, and even external simulators.

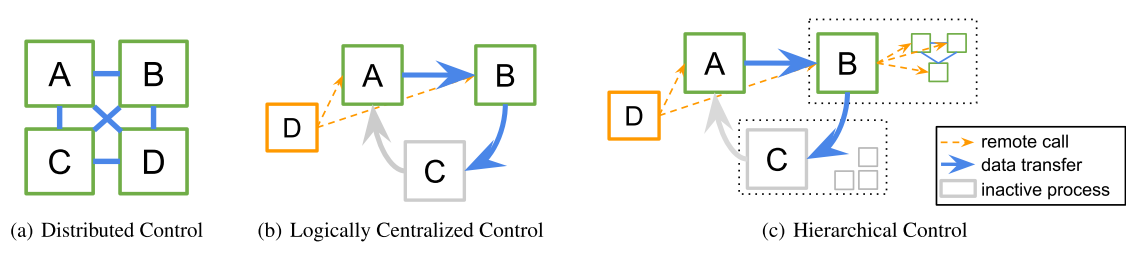

As a consequence, the developers have no choice but to use a hodgepodge(大杂烩)of frameworks to implement their algorithms, including parameter servers, collective(集体的)communication primitives in MPI-like frameworks, task queues, etc. For more complex algorithms, it is common to build custom distributed systems in which processes independently compute and coordinate among themselves with no central control (Figure 1(a)). While this approach can achieve high performance, the cost to develop and evaluate is large, not only due to the need to implement and debug distributed programs, but because composing these algorithms further complicates their implementation. Moreover, today’s computation frameworks (e.g., Spark, MPI) typically assume regular computation patterns and have difficulty when sub-tasks have varying durations, resource requirements, or nesting.

1.2 Logically centralized control for distributed RL

Most RL algorithms today are written in a fully distributed style (a) where replicated processes independently compute and coordinate with each other according to their roles (if any). We propose a hierarchical control model (c), which extends (b) to support nesting in RL and hyperparameter tuning workloads, simplifying and unifying the programming models used for implementation.

It is desirable for a single programming model to capture all the requirements of RL training. This can be done without eschewing(避免)high-level frameworks that structure the computation. Our key insight is that for each distributed RL algorithm, an equivalent algorithm can be written that exhibits logically centralized program control (Figure 1(b)). That is, instead of having independently executing processes (A, B, C, D in Figure 1(a)) coordinate among themselves (e.g., through RPCs, shared memory, parameter servers, or collective communication), a single driver program (D in Figure 1(b) and 1(c)) can delegate(委托)algorithm sub-tasks to other processes to execute in parallel. In this paradigm, the worker processes A, B, and C passively(被动地)hold state (e.g., policy or simulator state) but execute no computations until called by D. To support nested computations, we propose extending the centralized control model with hierarchical delegation of control (Figure 1(c)), which allows the worker processes (e.g., B, C) to further delegate work (e.g., simulations, gradient computation) to sub-workers of their own when executing tasks.

Figure 1

Building on such a logically centralized and hierarchical control model has several important advantages.

-

The equivalent algorithm is often easier to implement in practice, since the distributed control logic is entirely encapsulated in a single process rather than multiple processes executing concurrently.

-

The separation of algorithm components into sub-routines (e.g., do rollouts, compute gradients with respect to some policy loss), enables code reuse across different execution patterns. Sub-tasks that have different resource requirements (e.g., CPUs vs GPUs) can be placed on different machines, reducing compute costs.

-

Distributed algorithms written in this model can be seamlessly(无缝地)nested within each other, satisfying the parallelism encapsulation principle.

Logically centralized control models can be highly performant(高性能), our proposed hierarchical variant even more so. This is because the bulk of data transfer between processes happens out of band of the driver, not passing through any central bottleneck. In fact many highly scalable distributed systems leverage centralized control in their design. Within a single differentiable tensor graph, frameworks like TensorFlow also implement logically centralized scheduling of tensor computations onto available physical devices. Our proposal extends this principle into the broader ML systems design space.

The contributions of this paper are as follows.

-

We propose a general and composable hierarchical programming model for RL training.

-

We describe RLlib, our highly scalable RL library, and how it builds on the proposed model to provide scalable abstractions for a broad range of RL algorithms, enabling rapid development.

-

We discuss how performance is achieved within the proposed model, and show that RLlib meets or exceeds state-of-the-art performance for a wide variety of RL workloads.

2 Hierarchical Parallel Task Model

Parallelization of entire programs using frameworks like MPI and Distributed Tensorflow typically require explicit algorithm modifications to insert points of coordination when trying to compose two programs or components together. This limits the ability to rapidly prototype novel distributed RL applications.

We propose building RL libraries with hierarchical and logically centralized control on top of flexible task-based programming models like Ray. Task-based systems allow subroutines to be scheduled and executed asynchronously on worker processes, on a fine-grained basis, and for results to be retrieved or passed between processes.

2.1 Relation to existing distributed ML abstractions

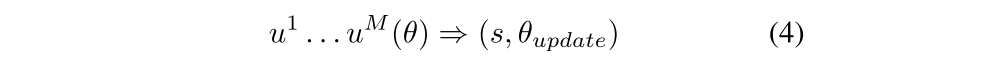

Though typically formulated for distributed control, abstractions such as parameter servers and collective communication operations can also be used within a logically centralized control model. As an example, RLlib uses allreduce and parameter-servers in some of its policy optimizers (Figure 2), and we will evaluate their performance.

2.2 Ray implementation of hierarchical control

We note that, within a single machine, the proposed programming model can be implemented simply with thread-pools and shared memory, though it is desirable for the underlying framework to scale to larger clusters if needed.

We chose to build RLlib on top of the Ray framework, which allows Python tasks to be distributed across large clusters. Ray’s distributed scheduler is a natural fit for the hierarchical control model, as nested computation can be implemented in Ray with no central task scheduling bottleneck.

To implement a logically centralized control model, it is first necessary to have a mechanism to launch new processes and schedule tasks on them. Ray meets this requirement with Ray actors, which are Python classes that may be created in the cluster and accept remote method calls (i.e., tasks). Ray permits these actors to in turn launch more actors and schedule tasks on those actors as part of a method call, satisfying our need for hierarchical delegation as well.

For performance, Ray provides standard communication primitives such as aggregate and broadcast, and critically enables the zero-copy sharing of large data objects through a shared memory object store.

3 Abstractions for Reinforcement Learning

To leverage RLlib for distributed execution, algorithms must declare their policy π, experience postprocessor ρ, and loss L. These can be specified in any deep learning framework, including TensorFlow and PyTorch. RLlib provides policy evaluators and policy optimizers that implement strategies for distributed policy evaluation and training.

3.1 Defining the Policy Graph

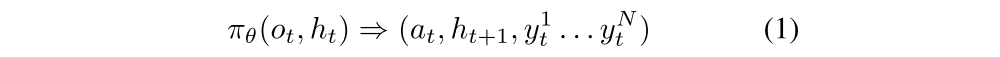

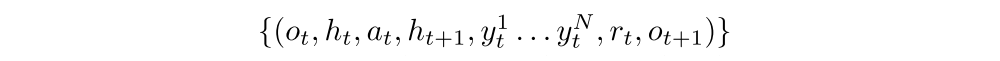

RLlib’s abstractions are as follows. The developer specifies a policy model π that maps the current observation ot and (optional) RNN hidden state ht to an action at and the next RNN state ht+1. Any number of user-defined values (e.g., value predictions, TD error) can also be returned:

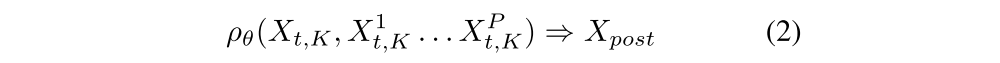

Most algorithms will also specify a trajectory post-processor ρ that transforms a batch Xt,K of K

tuples starting at t. Here rt and ot+1 are the reward and new observation after taking an action. To also support multi-agent environments, experience batches Xpt,K from the P other agents in the environment are also made accessible:

Gradient-based algorithms define a combined loss L that can be descended to improve the policy and auxiliary(辅助的)networks:

Finally, the developer can also specify any number of utility functions ui to be called as needed during training to, e.g., return training statistics s, update target networks, or adjust annealing(退火)schedules:

To interface with RLlib, these algorithm functions should be defined in a policy graph class with the following methods:

abstract class rllib.PolicyGraph:

def act(self, obs, h): action, h, y*

def postprocess(self, batch, b*): batch

def gradients(self, batch): grads

def get_weights; def set_weights;

def u*(self, args*)

3.2 Policy Evaluation

For collecting experiences, RLlib provides a PolicyEvaluator class that wraps a policy graph and environment to add a method to sample() experience batches. Policy evaluator instances can be created as Ray remote actors and replicated across a cluster for parallelism. To make their usage concrete, consider a minimal TensorFlow policy gradients implementation that extends the rllib.TFPolicyGraph helper template:

class PolicyGradient(TFPolicyGraph):

def __init__(self, obs_space, act_space):

self.obs, self.advantages = ...

pi = FullyConnectedNetwork(self.obs)

dist = rllib.action_dist(act_space, pi)

self.act = dist.sample()

self.loss = -tf.reduce_mean(

dist.logp(self.act) * self.advantages)

def postprocess(self, batch):

return rllib.compute_advantages(batch)

From this policy graph definition, the developer can create a number of policy evaluator replicas ev and call ev.sample.remote() on each to collect experiences in parallel from environments. RLlib supports OpenAI Gym, user-defined environments, and also batched simulators such as ELF:

evaluators = [rllib.PolicyEvaluator.remote(

env=SomeEnv, graph=PolicyGradient) for _ in range(10)]

print(ray.get([

ev.sample.remote() for ev in evaluators]))

3.3 Policy Optimization

RLlib separates the implementation of algorithms into the declaration of the algorithm-specific policy graph and the choice of an algorithm-independent policy optimizer. The policy optimizer is responsible for the performance-critical tasks of distributed sampling, parameter updates, and managing replay buffers. To distribute the computation, the optimizer operates over a set of policy evaluator replicas.

To complete the example, the developer chooses a policy optimizer and creates it with references to existing evaluators. The async optimizer uses the evaluator actors to compute gradients in parallel on many CPUs (Figure 2(c)). Each optimizer.step() runs a round of remote tasks to improve the model. Between steps, policy graph replicas can be queried directly, e.g., to print out training statistics:

optimizer = rllib.AsyncPolicyOptimizer(

graph=PolicyGradient, workers=evaluators)

while True:

optimizer.step()

print(optimizer.foreach_policy(

lambda p: p.get_train_stats()))

Policy optimizers extend the well-known gradient-descent optimizer abstraction to the RL domain. A typical gradient-descent optimizer implements step(L(θ),X, θ) ⇒ θopt. RLlib’s policy optimizers instead operate over the local policy graph G and a set of remote evaluator replicas, i.e., step(G, ev1 . . . evn, θ) ⇒ θopt, capturing the sampling phase of RL as part of optimization (i.e., calling sample() on policy evaluators to produce new simulation data).

The policy optimizer abstraction has the following advantages. By separating execution strategy from policy and loss definitions, specialized optimizers can be swapped in to take advantage of available hardware or algorithm features without needing to change the rest of the algorithm. The policy graph class encapsulates interaction with the deep learning framework, allowing algorithm authors to avoid mixing distributed systems code with numerical computations, and enabling optimizer implementations to be improved and reused across different deep learning frameworks.

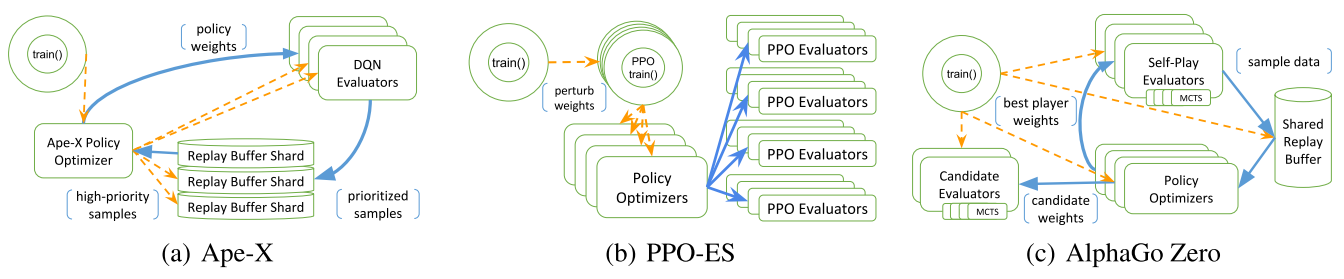

As shown in Figure 2, by leveraging centralized control, policy optimizers succinctly capture a broad range of choices in RL optimization: synchronous vs asynchronous, allreduce vs parameter server, and use of GPUs vs CPUs.

Figure 2

Figure 2 shows pseudocode for four RLlib policy optimizer step methods. Each step() operates over a local policy graph and array of remote evaluator replicas. Ray remote calls are highlighted in orange; other Ray primitives in blue. The apply() is shorthand for updating weights. Minibatch code and helper functions omitted. The param server optimizer in RLlib also implements pipelining not shown here.

RLlib’s policy optimizer abstraction is easy in a logically centralized control model since each policy optimizer has full control over the distributed computation it implements.

3.4 Completeness and Generality of Abstractions

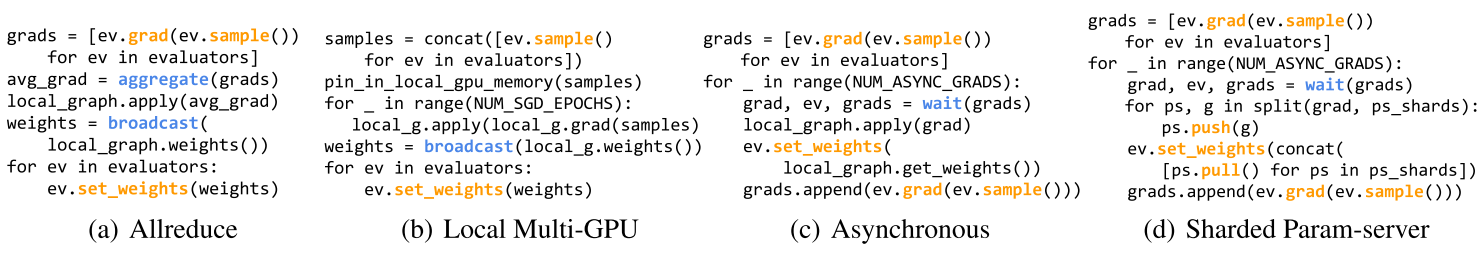

We demonstrate the completeness of RLlib’s abstractions by formulating the algorithm families listed in Table 1 within the API. When applicable, we also describe the concrete implementation in RLlib:

Table 1

RLlib’s policy optimizers and evaluators capture common components (Evaluation, Replay, Gradient-based Optimizer) within a logically centralized control model, and leverages Ray’s hierarchical task model to support other distributed components.

-

DQNs

DQNs use y1 for storing TD error, implement n-step return calculation in ρθ, and the Q loss in L. Target updates are implemented in u1, and setting the exploration ε in u2.

DQN implementation: To support experience replay, RLlib’s DQN uses a policy optimizer that saves collected samples in an embedded replay buffer. The user can alternatively use an asynchronous optimizer (Figure 2(c)). The target network is updated by calls to u1 between optimizer steps.

Ape-X implementation: Ape-X is a variation of DQN that leverages distributed experience prioritization to scale to many hundreds of cores. To adapt our DQN implementation, we created policy evaluators with a distribution of ε values, and wrote a new high-throughput policy optimizer (∼200 lines) that pipelines the sampling and transfer of data between replay buffer actors using Ray primitives. Our implementation scales nearly linearly up to 160k environment frames per second with 256 workers, and the optimizer can compute gradients for ∼8.5k 80×80×4 observations/s on a V100 GPU.

-

Policy Gradient / Off-policy PG

These algorithms store value predictions in y1, implement advantage estimation using ρθ, and combine actor and critic losses in L.

PPO implementation: Since PPO’s loss function permits multiple SGD passes over sample data, when there is sufficient GPU memory RLlib chooses a GPU-optimized policy optimizer (Figure 2(b)) that pins data into local GPU memory. In each iteration, the optimizer collects samples from evaluator replicas, performs multi-GPU optimization locally, and then broadcasts the new model weights.

A3C implementation: RLlib’s A3C can use either the asynchronous (Figure 2(c)) or sharded parameter server policy optimizer (2(d)). These optimizers collect gradients from the policy evaluators to update the canonical copy of θ.

DDPG implementation: RLlib’s DDPG uses the same replay policy optimizer as DQN. L includes both actor and critic losses. The user can also choose to use the Ape-X policy optimizer with DDPG.

-

Model-based / Hybrid

Model-based RL algorithms extend πθ(ot, ht) to make decisions based on model rollouts, which can be parallelized using Ray. To update their environment models, the model loss can either be bundled with L, or the model trained separately (i.e., in parallel using Ray primitives) and its weights periodically updated via u1.

-

Multi-Agent

Policy evaluators can run multiple policies at once in the same environment, producing batches of experience for each agent. Many multi-agent algorithms use a centralized critic or value function, which we support by allowing ρθ to collate(整理)experiences from multiple agents.

-

Evolutionary Methods

Derivative-free methods can be supported through non-gradient-based policy optimizers.

Evolution Strategies (ES) implementation: ES is a derivative- free optimization algorithm that scales well to clusters with thousands of CPUs. We were able to port a single-threaded implementation of ES to RLlib with only a few changes, and further scale it with an aggregation tree of actors, suggesting that the hierarchical control model is both flexible and easy to adapt algorithms for.

PPO-ES experiment: We studied a hybrid(混合)algorithm that runs PPO updates in the inner loop of an ES optimization step that randomly perturbs(扰乱)the PPO models. The implementation took only ∼50 lines of code and did not require changes to PPO, showing the value of encapsulating parallelism. In our experiments, PPO-ES converged faster and to a higher reward than PPO on the Walker2d-v1 task. A similarly modified A3C-ES implementation solved PongDeterministic-v4 in 30% less time.

-

AlphaGo

We sketch how to scalably implement the AlphaGo Zero algorithm using a combination of Ray and RLlib abstractions. Pseudocode for the ∼70 line main algorithm loop is provided in the Supplementary Material.

-

Logically centralized control of multiple distributed components: AlphaGo Zero uses multiple distributed components: model optimizers, self-play evaluators, candidate model evaluators, and the shared replay buffer. These components are manageable as Ray actors under a top-level AlphaGo policy optimizer. Each optimizer step loops over actor statuses to process new results, routing data between actors and launching new actor instances. -

Shared replay buffer: AlphaGo Zero stores the experiences from self-play evaluator instances in a shared replay buffer. This requires routing game results to the shared buffer, which is easily done by passing the result object references from actor to actor. -

Best player: AlphaGo Zero tracks the current best model and only populates its replay buffer with self-play from that model. Candidate models must achieve a ≥ 55% victory margin to replace the best model. Implementing this amounts to adding an if block in the main control loop. -

Monte-Carlo tree search: MCTS (i.e., model-based planning) can be handled as a subroutine of the policy graph, and optionally parallelized as well using Ray.

-

HyperBand and Population Based Training

Ray includes distributed implementations of hyperparameter search algorithms such as HyperBand and PBT. We were able to use these to evaluate RLlib algorithms, which are themselves distributed, with the addition of ∼15 lines of code per algorithm. We note that these algorithms are non-trivial(有意义的)to integrate when using distributed control models due to the need to modify existing code to insert points of coordination. RLlib’s use of short-running tasks avoids this problem, since control decisions can be easily made between tasks.

Figure 3