Paper 27: Emergence of Locomotion Behaviours in Rich Environments (DPPO)

Abstract

-

In practice, it is common to carefully hand-design the reward function to encourage a particular solution, or to derive it from demonstration data.

-

In this paper explore how a rich environment can help to promote the learning of complex behavior. Specifically, we train agents in diverse environmental contexts, and find that this encourages the emergence of robust behaviours that perform well across a suite of tasks.

-

We demonstrate this principle for locomotion–behaviours that are known for their sensitivity to the choice of reward. We train several simulated bodies on a diverse set of challenging terrains and obstacles, using a simple reward function based on forward progress.

-

Using a novel scalable variant of policy gradient RL, our agents learn to run, jump, crouch and turn as required by the environment without explicit reward-based guidance.

1 Introduction

What is common is that there is a well-defined reward function, such as the game score, which can be optimized to produce the desired behaviour. However, there are many tasks where the “right” reward function is less clear, and optimization of a naïvely selected one can lead to surprising results that do not match the expectations of the designer. This is particularly prevalent(流行的)in continuous control tasks, such as locomotion, and it has become standard practice to carefully handcraft the reward function, or else elicit a reward function from demonstrations.

Reward engineering has led to a number of successful demonstrations of locomotion behaviour, however, these examples are known to be brittle(脆弱的): they can lead to unexpected results if the reward function is modified even slightly, and for more advanced behaviours the appropriate reward function is often non-obvious in the first place. Also, arguably, the requirement of careful reward design sidesteps(回避)a primary challenge of RL: how an agent can learn for itself, directly from a limited reward signal, to achieve rich and effective behaviours. In this paper we return to this challenge.

Our premise(假定)is that rich and robust behaviours will emerge from simple reward functions, if the environment itself contains sufficient richness and diversity.

-

Firstly, an environment that presents a spectrum(频谱)of challenges at different levels of difficulty may shape learning and guide it towards solutions that would be difficult to discover in more limited settings.

-

Secondly, the sensitivity to reward functions and other experiment details may be due to a kind of overfitting, finding idiosyncratic(特殊的)solutions that happen to work within a specific setting, but are not robust when the agent is exposed to a wider range of settings. Presenting the agent with a diversity of challenges thus increases the performance gap between different solutions and may favor the learning of solutions that are robust across settings.

We focus on a set of novel locomotion tasks that go significantly beyond the previous state-of-the-art for agents trained directly from RL. They include a variety of obstacle courses for agents with different bodies (Quadruped, Planar Walker, and Humanoid). The courses are procedurally(程序上)generated such that every episode presents a different instance of the task.

Our environments include a wide range of obstacles with varying levels of difficulty (e.g. steepness, unevenness, distance between gaps).The variations in difficulty present an implicit curriculum to the agent – as it increases its capabilities it is able to overcome increasingly hard challenges, resulting in the emergence of ostensibly(表面上)sophisticated locomotion skills which may naïvely have seemed to require careful reward design or other instruction. We also show that learning speed can be improved by explicitly structuring terrains to gradually increase in difficulty so that the agent faces easier obstacles first and harder obstacles only when it has mastered the easy ones.

In order to learn effectively in these rich and challenging domains, it is necessary to have a reliable and scalable RL algorithm. We leverage components from several recent approaches to DRL.

-

First, we build upon robust policy gradient algorithms, such as TRPO and PPO, which bound parameter updates to a trust region to ensure stability.

-

Second, like the widely used A3C algorithm and related approaches we distribute the computation over many parallel instances of agent and environment. Our distributed implementation of PPO improves over TRPO in terms of wall clock time with little difference in robustness, and also improves over our existing implementation of A3C with continuous actions when the same number of workers is used.

The paper proceeds as follows. In Section 2 we describe the distributed PPO (DPPO) algorithm that enables the subsequent experiments, and validate its effectiveness empirically. Then in Section 3 we introduce the main experimental setup: a diverse set of challenging terrains and obstacles. We provide evidence in Section 4 that effective locomotion behaviours emerge directly from simple rewards; furthermore we show that terrains with a “curriculum” of difficulty encourage much more rapid progress, and that agents trained in more diverse conditions can be more robust.

2 Large scale reinforcement learning with Distributed PPO

Our focus is on RL in rich simulated environments with continuous state and action spaces. We require algorithms that are robust across a wide range of task variation, and that scale effectively to challenging domains. We address each of these issues in turn.

-

Robust policy gradients with Proximal Policy Optimization

We present a robust policy gradient algorithm, suitable for high-dimensional continuous control problems, that can be scaled to much larger domains using distributed computation.

Policy gradient estimates can have high variance and algorithms can be sensitive to the settings of their hyperparameters. Several approaches have been proposed to make policy gradient algorithms more robust. One effective measure is to employ a trust region constraint that restricts the amount by which any update is allowed to change the policy. A popular algorithm that makes use of this idea is TRPO. In every iteration given current parameters θold, TRPO collects a (relatively large) batch of data and optimizes the surrogate loss

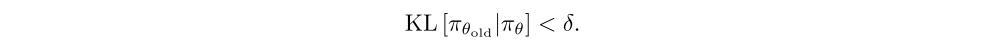

subject to a constraint on how much the policy is allowed to change, expressed in terms of the Kullback-Leibler divergence

Aθ is the advantage function given as

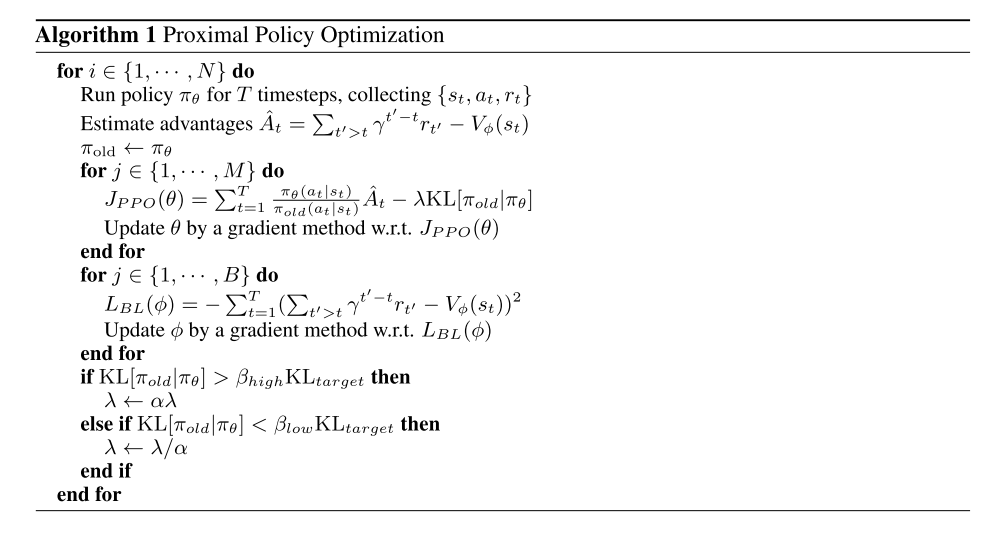

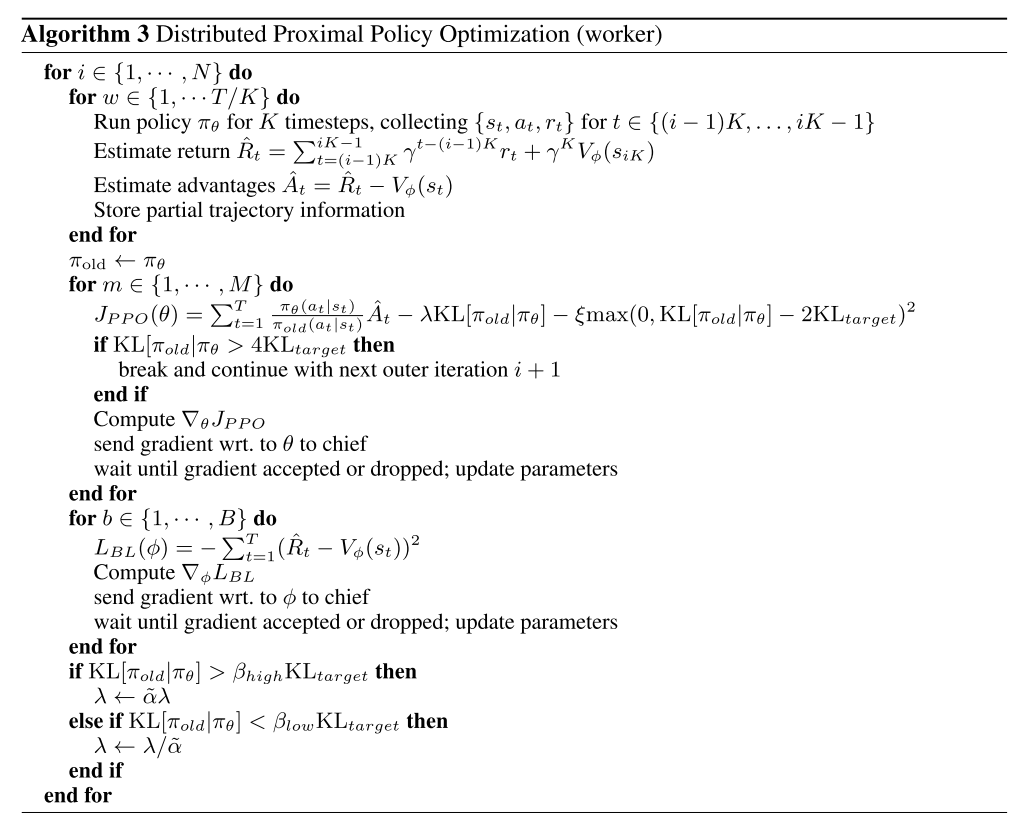

The PPO algorithm can be seen as an approximate version of TRPO that relies only on first order gradients, making it more convenient to use with RNNs and in a large-scale distributed setting. The trust region constraint is implemented via a regularization term. The coefficient of this regularization term is adapted depending on whether the constraint had previously been violated(违反)or not. Algorithm Box 1 shows the core PPO algorithm in pseudo-code.

The hyperparameter KLtarget is the desired change in the policy per iteration. The scaling term α > 1 controls the adjustment of the KL-regularization coefficient if the actual change in the policy stayed significantly below or significantly exceeded the target KL (i.e. falls outside the interval [βlowKLtarget, βhighKLtarget]).

-

Scalable reinforcement learning with Distributed PPO

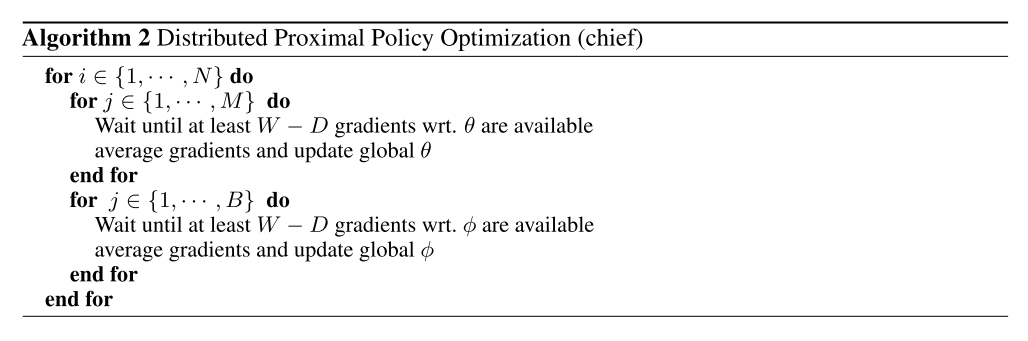

To achieve good performance in rich, simulated environments, we have implemented a distributed version of the PPO algorithm (DPPO). Data collection and gradient calculation are distributed over workers. We have experimented with both synchronous and asynchronous updates and have found that averaging gradients and applying them synchronously leads to better results in practice.

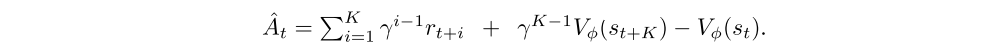

The original PPO algorithm estimates advantages using the complete sum of rewards. To facilitate the use of RNNs with batch updates while also supporting variable length episodes we follow a strategy similar to A3C and use truncated backpropagation through time with a window of length K. This makes it natural (albeit not a requirement) to use K-step returns also for estimating the advantage, i.e. we sum the rewards over the same K-step windows and bootstrap from the value function after K-steps:

The publicly available implementation of PPO by John Schulman adds several modifications to the core algorithm. These include normalization of inputs and rewards as well as an additional term in the loss that penalizes large violations of the trust region constraint. We adopt similar augmentations in the distributed setting but find that sharing and synchronization of various statistics across workers requires some care. The implementation of our distributed PPO (DPPO) is in TensorFlow, the parameters reside on a parameter server, and workers synchronize their parameters after every gradient step.

Pseudocode for the Distributed PPO algorithm is provided in Algorithm Boxes 2 and 3. W is the number of workers; D sets a threshold for the number of workers whose gradients must be available to update the parameters. M, B is the number of sub-iterations with policy and baseline updates given a batch of datapoints. T is the number of data points collected per worker before parameter updates are computed. K is the number of time steps for computing K-step returns and truncated backprop through time (for RNNs).

We perform the following normalization steps:

-

We normalize observations (or states st) by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation using the statistics aggregated over the course of the entire experiment.

-

We scale the reward by a running estimate of its standard deviation, again aggregated over the course of the entire experiment.

-

We use per-batch normalization of the advantages.

Sharing of algorithm parameters across workers: In the distributed setting we have found it to be important to share relevant statistics for data normalization across workers. Normalization is applied during data collection and statistics are updated locally after every environment step. Local changes to the statistics are applied to the global statistics after data collection when an iteration is complete (not shown in pseudo-code). The time-varying regularization parameter λ is also shared across workers but updates are determined based on local statistics based on the average KL computed locally for each worker, and applied separately by each worker with an adjusted ˜α = 1 + (α− 1)/K.

Additional trust region constraint: We also adopt an additional penalty term that becomes active when the KL exceeds the desired change by a certain margin (the threshold is 2KLtarget in our case). In our distributed implementation this criterion is tested and applied on a per-worker basis.

Stability is further improved by early stopping when changes lead to too large a change in the KL.

3 Methods: environments and models

Our goal is to study whether sophisticated locomotion skills can emerge from simple rewards when learning from varied challenges with a spectrum of difficulty levels. Having validated our scalable DPPO algorithm on simpler benchmark tasks, we next describe the settings in which we will demonstrate the emergence of more complex behavior.

3.1 Training environments

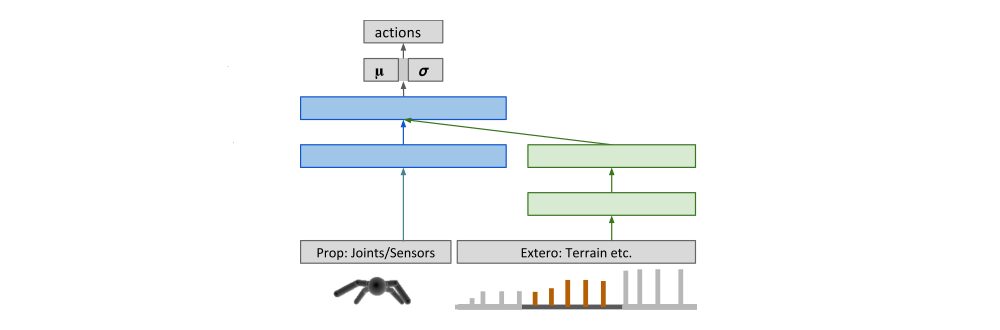

3.2 Policy parameterization

Schematic of the network architecture