Paper 29: Prioritized Experience Replay (PER)

Abstract

-

Experience replay lets online RL agents remember and reuse experiences from the past.

-

In prior work, experience transitions were uniformly sampled from a replay memory. This approach simply replays transitions at the same frequency that they were originally experienced, regardless of their significance.

-

In this paper we develop a framework for prioritizing experience, so as to replay important transitions more frequently, and therefore learn more efficiently.

1 Introduction

Two issues with online RL agents are

-

Strongly correlated updates that break the i.i.d. assumption of many popular stochastic gradient-based algorithms

-

The rapid forgetting of possibly rare experiences that would be useful later on.

Experience replay addresses both of these issues: with experience stored in a replay memory, it becomes possible to break the temporal correlations by mixing more and less recent experience for the updates, and rare experience will be used for more than just a single update.

In general, experience replay can reduce the amount of experience required to learn, and replace it with more computation and more memory – which are often cheaper resources than the RL agent’s interactions with its environment.

In this paper, we investigate how prioritizing which transitions are replayed can make experience replay more efficient and effective than if all transitions are replayed uniformly. The key idea is that an RL agent can learn more effectively from some transitions than from others. Transitions may be more or less surprising, redundant, or task-relevant. Some transitions may not be immediately useful to the agent, but might become so when the agent competence increases. Experience replay liberates(解放)online learning agents from processing transitions in the exact order they are experienced. Prioritized replay further liberates agents from considering transitions with the same frequency that they are experienced.

3 Prioritized Replay

Using a replay memory leads to design choices at two levels: which experiences to store, and which experiences to replay (and how to do so). This paper addresses only the latter: making the most effective use of the replay memory for learning, assuming that its contents are outside of our control.

3.2 Prioritizing with TD-error

The central component of prioritized replay is the criterion by which the importance of each transition is measured. One idealised criterion would be the amount the RL agent can learn from a transition in its current state (expected learning progress). While this measure is not directly accessible, a reasonable proxy is the magnitude of a transition’s TD error δ, which indicates how ‘surprising’ or unexpected the transition is: specifically, how far the value is from its next-step bootstrap estimate. This is particularly suitable for incremental, online RL algorithms, such as SARSA or Q-learning, that already compute the TD-error and update the parameters in proportion to δ. The TD-error can be a poor estimate in some circumstances as well, e.g. when rewards are noisy; see Appendix A for a discussion of alternatives.

Implementation: To scale to large memory sizes N, we use a binary heap data structure for the priority queue, for which finding the maximum priority transition when sampling is O(1) and updating priorities (with the new TD-error after a learning step) is O(logN).

3.3 Stochastic Prioritization

However, greedy TD-error prioritization has several issues.

-

First, to avoid expensive sweeps(扫描)over the entire replay memory, TD errors are only updated for the transitions that are replayed. One consequence is that transitions that have a low TD error on first visit may not be replayed for a long time (which means effectively never with a sliding window replay memory).

-

Further, it is sensitive to noise spikes (e.g. when rewards are stochastic), which can be exacerbated by bootstrapping, where approximation errors appear as another source of noise.

-

Finally, greedy prioritization focuses on a small subset of the experience: errors shrink slowly, especially when using function approximation, meaning that the initially high error transitions get replayed frequently. This lack of diversity that makes the system prone to over-fitting.

To overcome these issues, we introduce a stochastic sampling method that interpolates between pure greedy prioritization and uniform random sampling. We ensure that the probability of being sampled is monotonic in a transition’s priority, while guaranteeing a non-zero probability even for the lowest-priority transition. Concretely, we define the probability of sampling transition i as

where pi > 0 is the priority of transition i. The exponent α determines how much prioritization is used, with α = 0 corresponding to the uniform case.

-

The first variantwe consider is the direct, proportional prioritization where pi = |δi| + ε, where ε is a small positive constant that prevents the edge-case of transitions not being revisited once their error is zero. -

The second variantis an indirect, rank-based prioritization where pi = 1/rank(i), where rank(i) is the rank of transition i when the replay memory is sorted according to |δi|. In this case, P becomes a power-law distribution with exponent α.

Both distributions are monotonic in |δ|, but the latter is likely to be more robust, as it is insensitive to outliers.

Implementation: To efficiently sample from distribution (1), the complexity cannot depend on N. For the rank-based variant, we can approximate the cumulative(累积)density function with a piecewise(分段)linear function with k segments of equal probability. The segment boundaries can be precomputed (they change only when N or α change). At runtime, we sample a segment, and then sample uniformly among the transitions within it. This works particularly well in conjunction with a minibatch-based learning algorithm: choose k to be the size of the minibatch, and sample exactly one transition from each segment – this is a form of stratified(分层)sampling that has the added advantage of balancing out the minibatch (there will always be exactly one transition with high magnitude δ, one with medium magnitude, etc). The proportional variant is different, also admits an efficient implementation based on a ‘sum-tree’ data structure (where every node is the sum of its children, with the priorities as the leaf nodes), which can be efficiently updated and sampled from.

3.4 Annealing the Bias

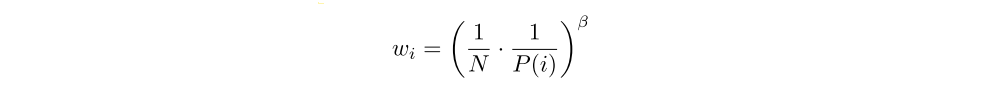

The estimation of the expected value with stochastic updates relies on those updates corresponding to the same distribution as its expectation. Prioritized replay introduces bias because it changes this distribution in an uncontrolled fashion, and therefore changes the solution that the estimates will converge to (even if the policy and state distribution are fixed). We can correct this bias by using importance-sampling (IS) weights

that fully compensates(补偿)for the non-uniform probabilities P(i) if β = 1. These weights can be folded into the Q-learning update by using wiδi instead of δi (this is thus weighted IS, not ordinary IS). For stability reasons, we always normalize weights by 1/maxi wi so that they only scale the update downwards.

In typical RL scenarios, the unbiased nature of the updates is most important near convergence at the end of training, as the process is highly non-stationary anyway, due to changing policies, state distributions and bootstrap targets; we hypothesize that a small bias can be ignored in this context. We therefore exploit the flexibility of annealing(退火)the amount of importance-sampling correction over time, by defining a schedule on the exponent β that reaches 1 only at the end of learning. In practice, we linearly anneal β from its initial value β0 to 1. Note that the choice of this hyperparameter interacts with choice of prioritization exponent α; increasing both simultaneously prioritizes sampling more aggressively at the same time as correcting for it more strongly.

Importance sampling has another benefit when combined with prioritized replay in the context of non-linear function approximation (e.g. deep neural networks): here large steps can be very disruptive(破坏性的), because the first-order approximation of the gradient is only reliable locally, and have to be prevented with a smaller global step-size. In our approach instead, prioritization makes sure high-error transitions are seen many times, while the IS correction reduces the gradient magnitudes (and thus the effective step size in parameter space), and allowing the algorithm follow the curvature of highly non-linear optimization landscapes because the Taylor expansion is constantly re-approximated.

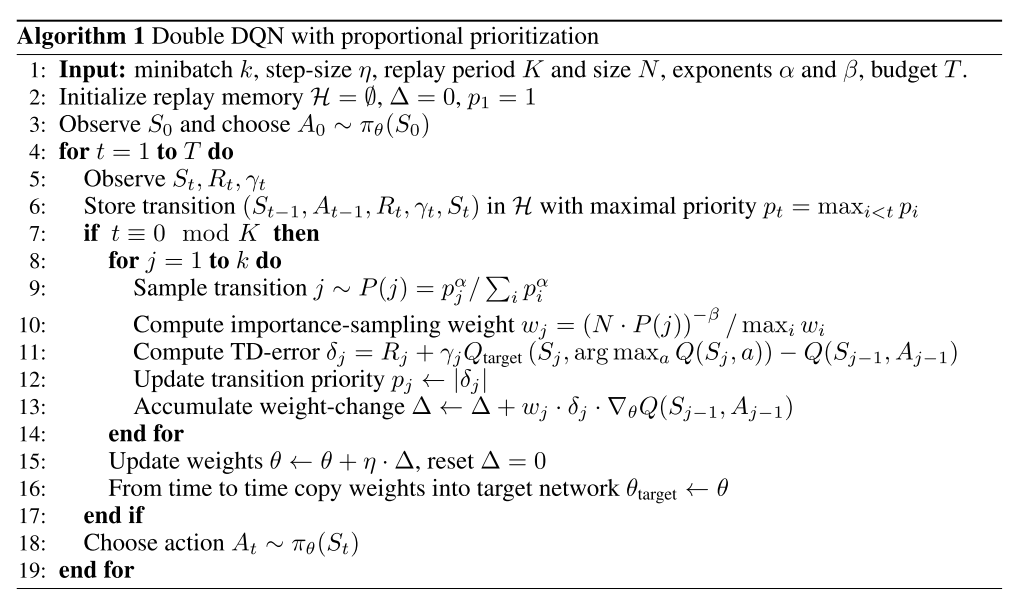

We combine our prioritized replay algorithm into a full-scale RL agent, based on the state-of-the-art Double DQN algorithm. Our principal modification is to replace the uniform random sampling used by Double DQN with our stochastic prioritization and importance sampling methods (see Algorithm 1).