Paper 32: A Closer Look at Deep Policy Gradients

Slides

Abstract

-

We study how the behavior of deep policy gradient algorithms reflects the conceptual framework motivating their development.

-

To this end, we propose a fine-grained analysis of SoTA methods based on key elements of this framework: gradient estimation, value prediction, and optimization landscapes.

-

Our results show that the behavior of deep policy gradient algorithms often deviates from what their motivating framework would predict: the surrogate objective does not match the true reward landscape, learned value estimators fail to fit the true value function, and gradient estimates poorly correlate with the “true” gradient.

-

The mismatch between predicted and empirical behavior we uncover highlights our poor understanding of current methods, and indicates the need to move beyond current benchmark-centric evaluation methods.

1 Introduction

The DRL toolkit has not yet attained the same level of engineering stability as, for example, the current deep (supervised) learning framework. Indeed, recent studies demonstrate that SoTA DRL algorithms suffer from oversensitivity to hyperparameter choices, lack of consistency, and poor reproducibility.

This state of affairs suggests that it might be necessary to re-examine the conceptual underpinnings(基础)of DRL methodology. More precisely, the overarching(首要的)question that motivates this work is:

To what degree does current practice in DRL reflect the principles informing its development?

Our specific focus is on deep policy gradient methods. Our goal is to explore the extent to which SoTA implementations of these methods succeed at realizing the key primitives of the general policy gradient framework.

Our contributions. We take a broader look at policy gradient algorithms and their relation to their underlying framework. With this perspective in mind, we perform a fine-grained examination of key RL primitives as they manifest in practice. Concretely, we study:

-

Gradient Estimation: we find that even when agents improve in reward, their gradient estimates used in parameter updates poorly correlate with the “true” gradient. We additionally show that gradient estimate quality decays with training progress and task complexity. Finally, we demonstrate that varying the sample regime(体系)yields training dynamics that are unexplained by the motivating framework and run contrary to supervised learning intuition. -

Value Prediction: our experiments indicate that value networks successfully solve the supervised learning task they are trained on, but do not fit the true value function. Additionally, employing a value network as a baseline function only marginally decreases the variance of gradient estimates compared to using true value as a baseline (but still dramatically increases agent’s performance compared to using no baseline at all). -

Optimization Landscapes: we show that the optimization landscape induced by modern policy gradient algorithms is often not reflective of the underlying true reward landscape, and that the latter is frequently poorly behaved in the relevant sample regime.

Overall, our results demonstrate that the motivating theoretical framework for DRL algorithms is often unpredictive of phenomena arising in practice. This suggests that building reliable DRL algorithms requires moving past benchmark-centric evaluations to a multi-faceted understanding of their often unintuitive behavior. We conclude by discussing several areas where such understanding is most critically needed.

2 Examining the Primitives of Deep Policy Gradient Algorithms

In this section, we investigate the degree to which our theoretical understanding of RL applies to modern methods. We consider key primitives of policy gradient algorithms: gradient estimation, value prediction and reward fitting. In what follows, we perform a fine-grained analysis of SoTA policy gradient algorithms (PPO and TRPO) through the lens of these primitives.

2.1 Gradient Estimate Quality

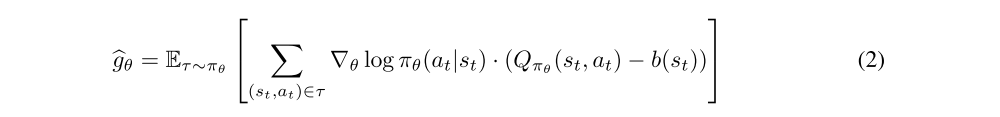

A central premise of policy gradient methods is that stochastic gradient ascent on a suitable objective function yields a good policy. These algorithms use as a primitive the gradient of that objective function:

An underlying assumption behind these methods is that we have access to a reasonable estimate of this quantity. This assumption effectively translates into an assumption that we can accurately estimate the expectation above using an empirical mean of finite (typically ∼ 1000) samples. Evidently (since the agent attains a high reward) these estimates are sufficient to consistently improve reward—we are thus interested in the relative quality of these gradient estimates in practice, and the effect of gradient quality on optimization.

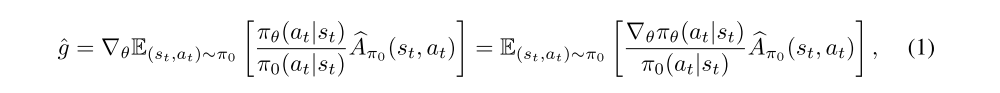

How accurate are the gradient estimates we compute? To answer this question, we examine two of the most natural measures of estimate quality: the empirical variance and the convergence to the “true” gradient. To evaluate the former, we measure the average pairwise cosine similarity between estimates of the gradient computed from the same policy with independent rollouts.

Figure 1: Empirical variance of the estimated gradient as a function of the number of state-action pairs used in estimation in the MuJoCo Humanoid task.

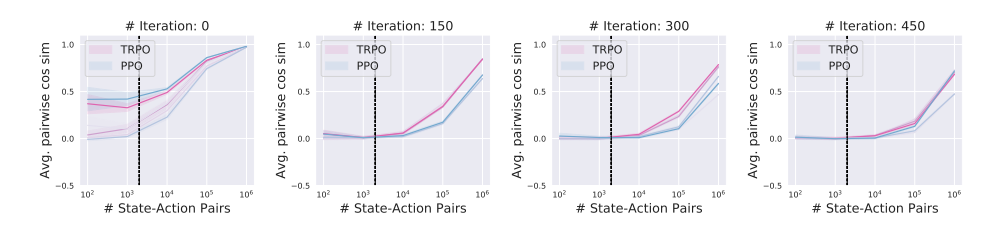

We evaluate the latter by first forming an estimate of the true gradient with a large number of state-action pairs. We then examine the convergence of gradient estimates to this “true” gradient (which we once again measure using cosine similarity) as we increase the number of samples.

Figure 2: Convergence of gradient estimates to the “true” expected gradient in the MuJoCo Humanoid task.

We observe that deep policy gradient methods operate with relatively poor estimates of the gradient, especially as task complexity increases and as training progresses. This is in spite of the fact that our agents continually improve throughout training, and attain nowhere near the maximum reward possible on each task. In fact, we sometimes observe a zero or even negative correlation in the relevant sample regime.

While these results might be reminiscent of the well-studied “noisy gradients” problem in supervised learning, we have very little understanding of how gradient quality affects optimization in the substantially different RL setting. For example:

-

The sample regime in which RL algorithms operate seems to have a profound impact on the robustness and stability of agent training — in particular, many of the sensitivity issues are claimed to disappear in higher-sample regimes. Understanding the implications of working in this sample regime, and more generally

the impact of sample complexity on training stability remains to be precisely understood. -

Agent policy networks are trained concurrently with value networks meant to reduce the variance of gradient estimates. Under our conceptual framework, we might expect these networks to help gradient estimates more as training progresses, contrary to what we observe in Figure 1.

The value network also makes the now two-player optimization landscape and training dynamics even more difficult to grasp, as such interactions are poorly understood. -

The relevant measure of sample complexity for many settings (number of state-action pairs) can differ drastically from the number of independent samples used at each training iteration (the number of complete trajectories). The latter quantity (a) tends to be much lower than the number of state-action pairs, and (b) decreases across iterations during training.

All the above factors make it unclear to what degree our intuition from classical settings transfer to the DRL regime. And the ` policy gradient framework, as of now, provides little predictive power regarding the variance of gradient estimates and its impact on reward optimization`.

Our results indicate that despite having a rigorous theoretical framework for RL, we lack a precise understanding of the structure of the reward landscape and optimization process.

2.2 Value Prediction

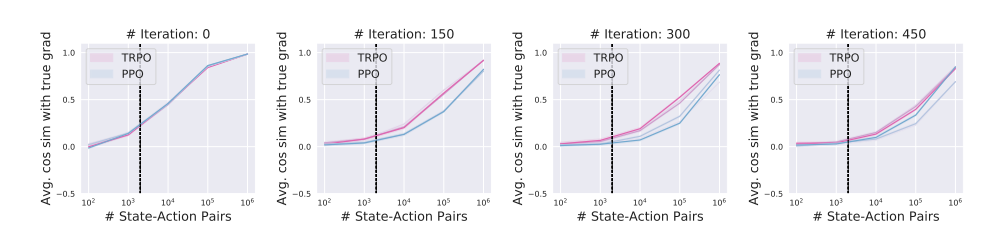

Our findings from the previous section motivate a deeper look into gradient estimation. After all, the policy gradient in its original formulation is known to be hard to estimate, and thus algorithms employ a variety of variance reduction methods. The most popular of these techniques is a baseline function. Concretely, an equivalent form of the policy gradient is given by:

where b(st) is some fixed function of the state st. A canonical choice of baseline function is the value function Vπ(s), the expected return from a given state

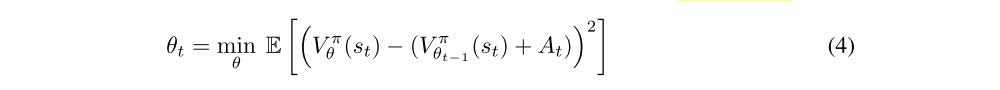

Indeed, fitting a value-estimating function (a neural network, in the DRL setting) and using it as a baseline function is precisely the approach taken by most deep policy gradient methods. Concretely, one trains a value network such that:

At is the advantage of the policy, i.e. the returns minus the estimated values. (Typically, At is estimated using GAE). Our findings in the previous section prompt us to take a closer look at the value network and its impact on the variance of gradient estimates.

Value prediction as a supervised learning problem. We first analyze the value network through the lens of the supervised learning problem it solves. After all, (4) describes an empirical risk minimization, where a loss is minimized over a set of sampled (st, at). So, how does Vπθ perform as a solution to (4)? And in turn, how does (4) perform as a proxy for learning the true value function?

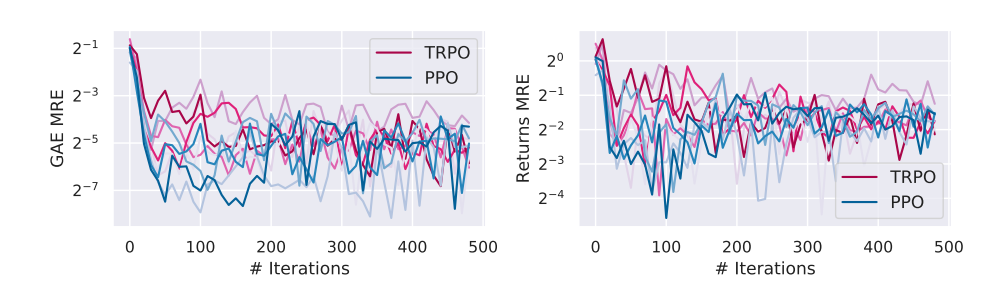

Our results (Figure 3) show that the value network does succeed at both fitting the given loss function and generalizing to unseen data, showing low and stable mean relative error (MRE). However, the significant drop in performance as shown in Figure 3 indicates that the supervised learning problem induced by (4) does not lead to Vπθ learning the underlying true value function.

Figure 3: Quality of value prediction in terms of mean relative error (MRE) on heldout state-action pairs for agents trained to solve the MuJoCo Walker2d-v2 task.

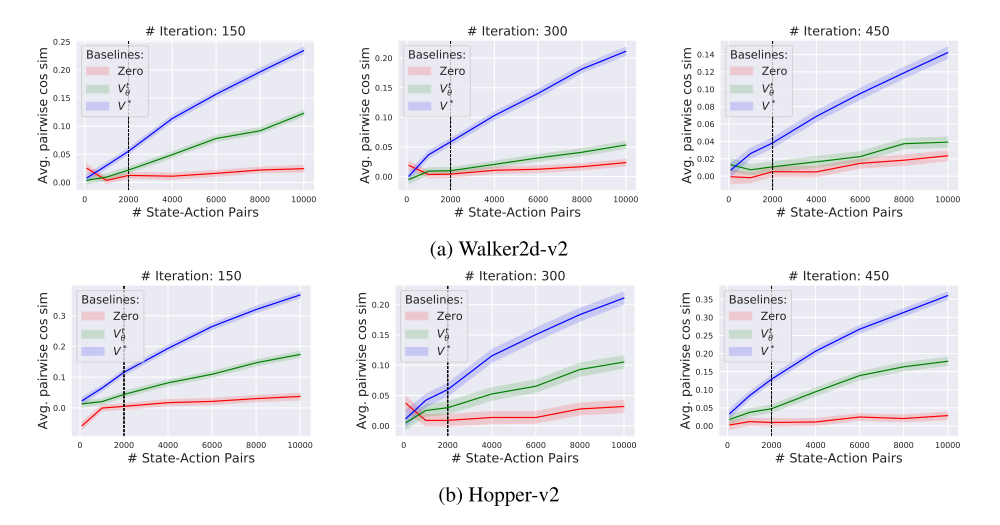

Does the value network lead to a reduction in variance? Though evaluating the Vπθ baseline function as a value predictor as we did above is informative, in the end the sole purpose of the value function is to reduce variance. So: how does using our value function actually impact the variance of our gradient estimates? To answer this question, we compare the variance reduction that results from employing our value network against both a “true” value function and a trivial “zero” baseline function (i.e. simply replacing advantages with returns).

Our results, captured in Figure 4, show that the “true” value function yields a much lower-variance estimate of the gradient. This is especially true in the sample regime in which we operate. We note, however, that despite not effectively predicting the true value function or inducing the same degree of variance reduction, the value network does help to some degree (compared to the “zero” baseline). Additionally, the seemingly marginal increase in gradient correlation provided by the v`alue network (compared to the “true” baseline function) turns out to result in a significant improvement in agent performance. (Indeed, agents trained without a baseline reach almost an order of magnitude worse reward.)

Figure 4: Efficacy of the value network as a variance reducing baseline for Walker2d-v2 (top) and Hopper-v2 (bottom) agents.

Our findings suggest that we still need a better understanding of the role of the value network in agent training, and raise several questions that we discuss in Section 3.

2.3 Exploring the Optimization Landscape

Another key assumption of policy gradient algorithms is that first-order updates (w.r.t. policy parameters) actually yield better policies. It is thus natural to examine how valid this assumption is.

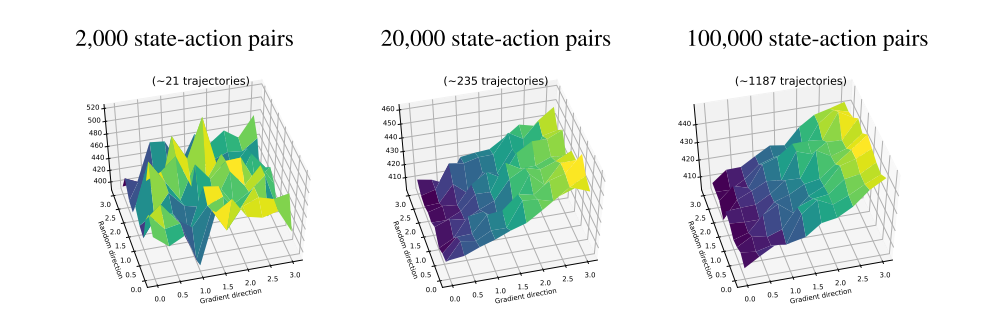

The true rewards landscape. We begin by examining the landscape of agent reward with respect to the policy parameters. Indeed, even if deep policy gradient methods do not optimize for the true reward directly (e.g. if they use a surrogate objective), the ultimate goal of any policy gradient algorithm is to navigate this landscape. First, Figure 5 shows that while estimating the true reward landscape with a high number of samples yields a relatively smooth reward landscape (perhaps suggesting viability of direct reward optimization), estimating the true reward landscape in the typical, low sample regime results in a landscape that appears jagged(参差不齐的)and poorly-behaved. The low-sample regime thus gives rise to a certain kind of barrier to direct reward optimization. Indeed, applying our algorithms in this regime makes it impossible to distinguish between good and bad points in the landscape, even though the true underlying landscape is fairly well-behaved.

Figure 5: True reward landscape concentration for TRPO on Humanoid-v2.

The surrogate objective landscape. The untamed(未开发的)nature of the rewards landscape has led to the development of alternate approaches to reward maximization. Recall that an important element of many modern policy gradient methods is the maximization of a surrogate objective function in place of the true rewards. The surrogate objective, based on relaxing the policy improvement, can be viewed as a simplification of the reward maximization objective.

As a purported approximation of the true returns, one would expect that the surrogate objective landscape approximates the true reward landscape fairly well. That is, parameters corresponding to good surrogate objective will also correspond to good true reward.

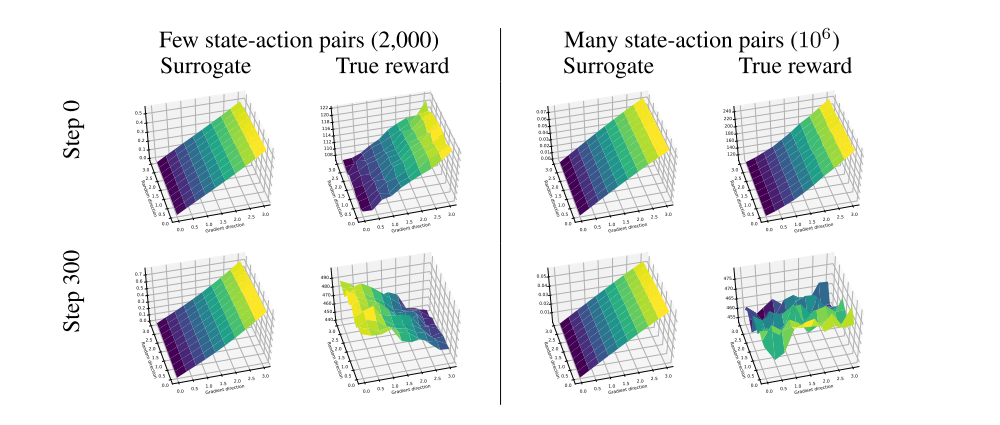

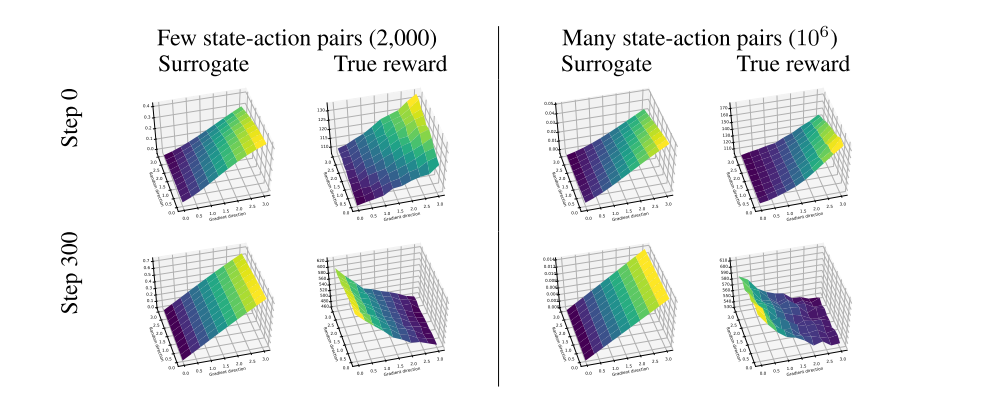

Figure 6 shows that in the early stages of training, the optimization landscapes of the true reward and surrogate objective are indeed approximately aligned. However, as training progresses, the surrogate objective becomes much less predictive of the true reward in the relevant sample regime. In particular, we often observe that directions that increase the surrogate objective lead to a decrease of the true reward (see Figures 6, 7). In a higher-sample regime (using several orders of magnitude more samples), we find that PPO and TRPO turn out to behave rather differently. In the case of TRPO, the update direction following the surrogate objective matches the true reward much more closely. However, for PPO we consistently observe landscapes where the step direction leads to lower true reward, even in the high-sample regime. This suggests that even when estimated accurately enough, the surrogate objective might not be an accurate proxy for the true reward. (Recall from Section 2.1 that this is a sample regime where we are able to estimate the true gradient of the reward fairly well.)

Figure 6: True reward and surrogate objective landscapes for TRPO on the Humanoid-v2 MuJoCo task.

Figure 7: True reward and surrogate objective landscapes for PPO on the Humanoid-v2 MuJoCo task.

3 Towards Stronger Foundations for Deep RL

DRL algorithms have shown great practical promise, and are rooted in a well-grounded theoretical framework. However, our results indicate that this framework often fails to provide insight into the practical performance of these algorithms. This disconnect impedes(阻碍)our understanding of why these algorithms succeed (or fail), and is a major barrier to addressing key challenges facing DRL such as brittleness(脆弱)and poor reproducibility.

To close this gap, we need to either develop methods that adhere(遵守)more closely to theory, or build theory that can capture what makes existing policy gradient methods successful. In both cases, the first step is to precisely pinpoint where theory and practice diverge. To this end, we analyze and consolidate(巩固)our findings from the previous section.

-

Gradient estimation.

Our analysis in Section 2.1 shows that the quality of gradient estimates that deep policy gradient algorithms use is rather poor. Indeed, even when agents improve, such gradient estimates often poorly correlate with the true gradient. We also note that gradient correlation decreases as training progresses and task complexity increases. While this certainly does not preclude(排除)the estimates from conveying useful signal, the exact underpinnings of this phenomenon in DRL still elude us. In particular, in Section 2.1 we outline a few keys ways in which the DRL setting is quite unique and difficult to understand from an optimization perspective, both theoretically and in practice Overall,understanding the impact of gradient estimate quality on DRL algorithms is challenging and largely unexplored.

-

Value prediction.

The findings presented in Section 2.2 identify two key issues. First, while the value network successfully solves the supervised learning task it is trained on, it does not accurately model the “true” value function. Second, employing the value network as a baseline does decrease the gradient variance (compared to the trivial (“zero”) baseline). However, this decrease is rather marginal compared to the variance reduction offered by the “true” value function.

It is natural to wonder whether this failure in modeling the value function is inevitable. For example, how does the loss function used to train the value network impact value prediction and variance reduction? More broadly, we lack an understanding of the precise role of the value network in training. Can we empirically quantify the relationship between variance reduction and performance? And does the value network play a broader role than just variance reduction?

-

Optimization landscape.

We have also seen, in Section 2.3, that the optimization landscape induced by modern policy gradient algorithms, the surrogate objective, is often not reflective of the underlying true reward landscape. We thus need a deeper understanding of why current methods succeed despite these issues, and, more broadly, how to better navigate the true reward landscape.

A Appendix

A.1 Background

-

Surrogate Objective.

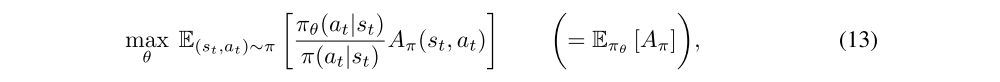

So far, our focus has been on extracting a good estimate of the gradient with respect to the policy parameters θ. However, it turns out that directly optimizing the cumulative rewards can be challenging. Thus, a modification used by modern policy gradient algorithms is to optimize a “surrogate objective” instead. We will focus on maximizing the following local approximation of the true reward:

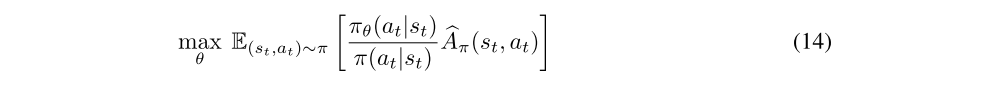

or the normalized advantage variant proposed to reduce variance

where

and π is the current policy.

-

Trust region methods.

The surrogate objective function, although easier to optimize, comes at a cost: the gradient of the surrogate objective is only predictive of the policy gradient locally (at the current policy). Thus, to ensure that our update steps we derive based on the surrogate objective are predictive, they need to be confined to a “trust region” around the current policy. The resulting trust region methods try to constrain the local variation of the parameters in policy-space by restricting the distributional distance between successive policies.

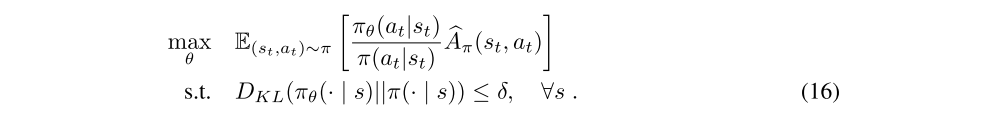

A popular method in this class is TRPO, which constrains the KL divergence between successive policies on the optimization trajectory, leading to the following problem:

In practice, this objective is maximized using a second-order approximation of the KL divergence and natural gradient descent, while replacing the worst-case KL constraints over all possible states with an approximation of the mean KL based on the states observed in the current trajectory.

-

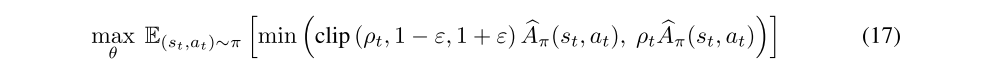

Proximal policy optimization.

In practice, the TRPO algorithm can be computationally costly — the step direction is estimated with nonlinear conjugate gradients, which requires the computation of multiple Hessian-vector products. To address this issue, PPO was proposed, which utilizes a different objective and does not compute a projection. Concretely, PPO proposes replacing the KL-constrained objective (16) of TRPO by clipping the objective function directly as:

where