Paper 33: Implementation Matters in Deep Policy Gradients: A Case Study on PPO and TRPO

Abstract

-

We study the roots of algorithmic progress in deep policy gradient algorithms through a case study on two popular algorithms, PPO and TRPO.

-

We investigate the consequences of “code-level optimizations”: algorithm augmentations found only in implementations or described as auxiliary details to the core algorithm. Seemingly of secondary importance, such optimizations have a major impact on agent behavior.

-

Our results show that they (a) are responsible for most of PPO’s gain in cumulative reward over TRPO, and (b) fundamentally change how RL methods function. These insights show the difficulty, and importance, of attributing performance gains in DRL.

1 Introduction

We do not understand how the parts comprising DRL algorithms impact agent training, either separately or as a whole. This unsatisfactory understanding suggests that we should re-evaluate the inner workings of our algorithms. Indeed, the overall question motivating our work is: how do the multitude of mechanisms used in DRL training algorithms impact agent behavior?

Our contributions. We will specifically analyze the underpinnings of agent behavior — both cumulative reward, as well as more fine-grained algorithmic properties. As a first step towards tackling this question, we conduct a case study of two of the most popular deep policy-gradient methods: TRPO and PPO. These algorithms are closely related: PPO was originally developed as a refinement of TRPO.

We find that much of the method’s performance comes from various code-level or implementation optimizations not present in TRPO: seemingly small modifications to the core algorithm either found only in a paper’s original implementation, or described as auxiliary details. We pinpoint these optimizations, and run an ablation study(消融实验)demonstrating that they are instrumental(有用的)to the PPO’s performance.

This observations prompt us to study how such code-level optimizations change agent training dynamics, and whether we can truly think of them as merely auxiliary improvements. Our results indicate that code-level optimizations fundamentally change algorithms’ operation, going beyond improvements in agent reward. Concretely, we find that these optimizations are in fact essential for satisfying a key motivating principle behind TRPO and PPO’s operations: trust region enforcement. Additionally, we find that these optimizations are both necessary and sufficient to maintain a trust region, regardless of whether or not the clipping algorithm — typically thought to be the central algorithm of PPO — is employed.

Ultimately, we find that the PPO code-optimizations are significantly more important in terms of final reward achieved than the choice of general training algorithm (TRPO vs. PPO). This result is in stark contrast to the previous view that the central PPO clipping method drives the gains. In doing so, we demonstrate that the algorithmic changes imposed by such optimizations make rigorous(严格的)comparisons of algorithms difficult. Without a rigorous understanding of the full impact of code-level optimizations, we cannot hope to gain any reliable insight from comparing algorithms on benchmark tasks.

Our results emphasize the importance of building RL methods in a modular manner. To progress towards more performant and reliable algorithms, we need to understand each component’s impact on agent behavior and performance - both individually, and as part of a whole.

2 Attributing Success in Proximal Policy Optimization

Our overarching goal is to better understand the underpinnings of the behavior of deep policy gradient methods. We thus perform a careful study of two tightly linked algorithms: TRPO and PPO. To better understand these methods, we start by thoroughly investigating their implementations in practice. We find that in comparison to TRPO, the PPO implementation contains many non-trivial optimizations that are not (or only barely) described in its corresponding paper. Indeed, the standard implementation of PPO contains the following additional optimizations (among many others; we provide a full list in Appendix A.2):

-

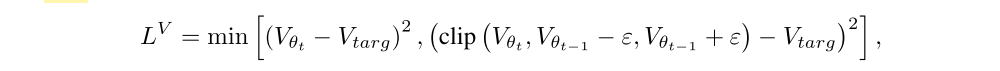

Value function clipping

It was originally suggested to fit the value network via regression to target values:

but in the standard implementation the value network is instead fit with a PPO-like objective:

where Vθ is clipped around the previous value estimates (and ε is fixed to the same value as the value used in (2) to clip the probability ratios).

-

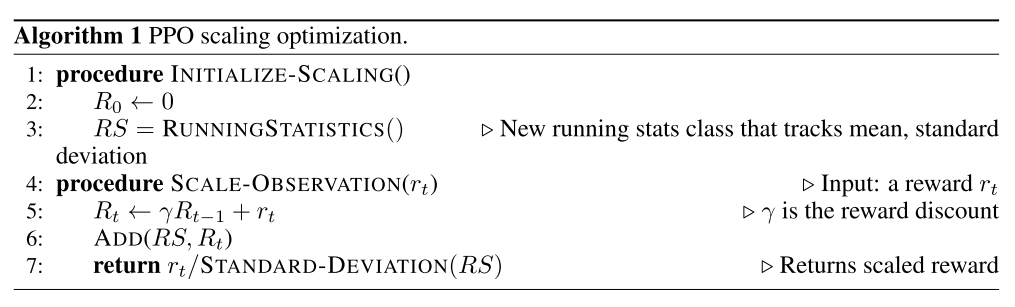

Reward scaling

Rather than feeding the rewards directly from the environment into the objective, the PPO implementation performs a certain discount-based scaling scheme. In this scheme, the rewards are divided through by the standard deviation of a rolling discounted sum of the rewards (without subtracting and re-adding the mean) — see Algorithm 1 in Appendix A.2.

-

Orthogonal initialization and layer scaling

Instead of using the default weight initialization scheme for the policy and value networks, the implementation uses an orthogonal initialization scheme with scaling that varies from layer to layer.

-

Adam learning rate annealing

Depending on the task, the implementation sometimes anneals the learning rate of Adam (an already adaptive method) for optimization.

These optimizations may appear as merely surface-level or insignificant algorithmic changes to the core policy gradient method at hand. However, we find that they dramatically affect the performance of PPO. To demonstrate this, we start by performing a full ablation study on the four optimizations mentioned above.

Our results show that reward normalization, Adam annealing, and network initialization are crucial to obtaining the best average reward with PPO. We detail our experimental setup in Appendix A.1.

The above findings show that our ability to understand PPO from an algorithmic perspective hinges on the ability to distill out its fundamental principles from such algorithm-independent (in the sense that these optimizations can be implemented for any policy gradient method) optimizations. We thus consider a variant of PPO called PPO-MINIMAL (PPO-M) which implements only the core of the algorithm. PPO-M uses the standard value network loss, no reward scaling, the default network initialization, and Adam with a fixed learning rate (PPO-M ignores a host of other code-level optimizations as well; see Appendix A.2). We then explore PPO-M alongside PPO and TRPO as a “vanilla” version of PPO.

Overall, our results on the importance of these optimizations both corroborate(确证)results demonstrating the brittleness of deep policy gradient methods, and demonstrate that even beyond environmental brittleness, the algorithms themselves exhibit high sensitivity to implementation choices.

3 Code-level Optimizations have Algorithmic Effects

In the previous section, we found that canonical implementations of PPO contain many code-level optimizations: implementation choices that are not motivated as core to a method but profoundly impact performance.

This mismatch leads us to ask: how do these seemingly superficial(肤浅的)code-level optimizations impact underlying agent behavior? In this section, we demonstrate that the code-level optimizations fundamentally alter agent behavior. Rather than merely improving ultimate cumulative award, such optimizations directly impact the principles motivating the core algorithms.

-

Trust Region Optimization.

A key property of policy gradient algorithms is that update steps computed at any specific policy πθt are only guaranteed predictiveness in a neighborhood around θt. Thus, to ensure that the update steps we derive remain predictive many policy gradient algorithms ensure that these steps stay in the vicinity of the current policy. The resulting “trust region” methods try to constrain the local variation of the parameters in policy-space by restricting the distributional distance between successive policies.

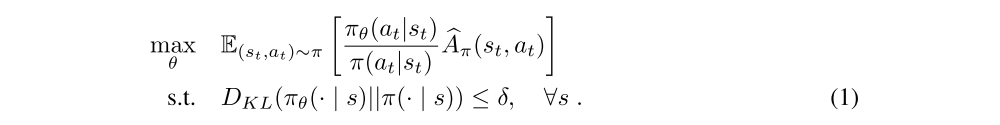

A popular method in this class is TRPO. TRPO constrains the KL divergence between successive policies on the optimization trajectory, leading to the following problem:

In practice, we maximize this objective with a second-order approximation of the KL divergence and natural gradient descent, and replace the worst-case KL constraints over all possible states with an approximation of the mean KL based on the states observed in the current trajectory.

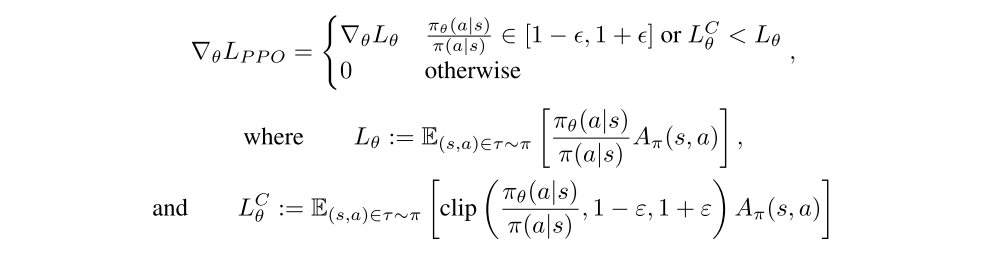

One disadvantage of the TRPO algorithm is that it can be computationally costly — the step direction is estimated with nonlinear conjugate gradients, which requires the computation of multiple Hessian-vector products. To address this issue, PPO was proposed, which tries to enforce a trust region with a different objective that does not require computing a projection. Concretely, PPO proposes replacing the KL-constrained objective (1) of TRPO by clipping the objective function directly as:

where

In addition to its simplicity, PPO is intended to be faster and more sample-efficient than TRPO.

-

Trust regions in TRPO and PPO.

Enforcing a trust region is a core algorithmic property of different policy gradient methods. However, whether or not a trust region is enforced is not directly observable from the final rewards. So, how does this algorithmic property vary across SoTA policy gradient methods?

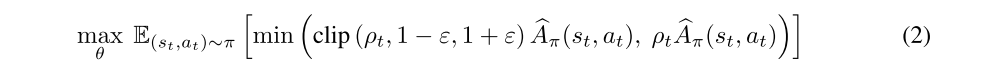

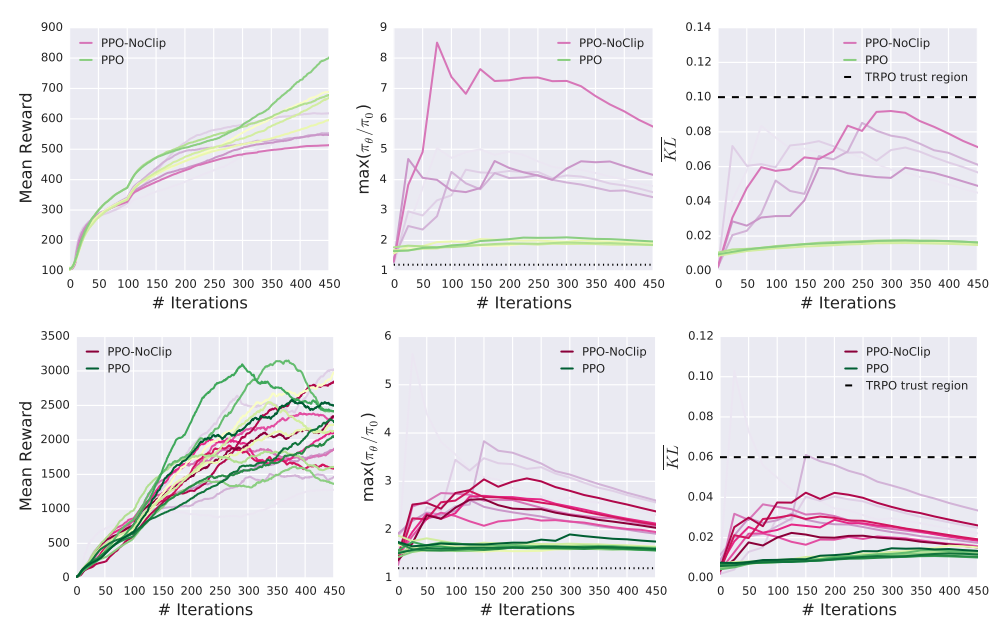

In Figure 1 we measure the mean KL divergence between successive policies in a training run of both TRPO and PPO-M. Recall that TRPO is designed specifically to constrain this KL-based trust region, while the clipping mechanism of PPO attempts to approximate it. Indeed, while TRPO precisely enforcing this trust region, the successive KL divergence between policies in PPO-M grows exponentially as training progresses.

From the plots we can see that the PPO variants’ maximum ratios consistently violates the ratio “trust region”. We additionally see that while PPO constrains the mean KL well, PPO-M does not, suggesting that the core PPO algorithm is not sufficient to maintain a ratio “trust region”. We additionally measure the quantities over a heldout set of state-action pairs and find little qualitative difference in the results (seen in the appendix), suggesting that TRPO does indeed enforce a mean KL trust region. We show plots for additional tasks in the Appendix. We detail our experimental setup in Appendix A.1.

Figure 1: Per step mean reward, maximum ratio, mean KL, and maximum versus mean KL for agents trained to solve the MuJoCo Humanoid task.

While this may seem surprising at first, we find that the unbounded nature of the trust region actually follows naturally from the clipping mechanism of PPO. In particular, the contribution of a single state-action pair to the gradient of the PPO objective is given by:

are respectively the standard and clipped versions of the surrogate reward. As a result, since we initialize πθ as π (and thus the ratios start all equal to one) the first step we take is identical to a maximization step over the unclipped surrogate reward. Therefore, the size of step we take is determined solely be the steepness of the surrogate landscape (i.e. Lipschitz constant of the optimization problem we solve), and we can end up moving arbitrarily far from the trust region. In fact, observe in Figure 1 that PPO-M fails at even maintaining a trust region based on the maximum ratio (i.e., the exact quantity that PPO tries to control via clipping).

Remarkably, despite that the core mechanism of PPO (which is captured in PPO-M) fails to maintain a trust region, we find that PPO with optimizations actually does seem to maintain a KL-based trust region. This demonstrates that perhaps the key to PPO’s success even from an algorithmic viewpoint comes from auxiliary optimizations, rather than the core methodology.

-

Enforcing a trust region without projecting or clipping.

It turns out that code-level optimizations alone enforce a trust region without clipping the objective function or explicitly bounding the distance between successive policies. Indeed, Figure 2 demonstrates that PPO-NOCLIP (PPO without clipping) can actually maintain reasonable trust regions on benchmark tasks when operating in conjunction with the right optimizations. The trust region for PPO-NOCLIP bounds KL to a lesser degree than the KL bound seen in TRPO (represented by the horizontal, black dotted line in the mean KL plot), and we do not observe the same exponentially increasing trend we found in PPO-M in Figure 1.

Figure 2: Per step mean reward, maximum ratio, mean KL, and mean KL for PPO and PPO-NOCLIP agents trained to solve the MuJoCo Humanoid-v2 (top) and Hopper-v2 (bottom) task.

Overall, our results indicate that so-called code-level optimizations do not merely increase performance: they fundamentally change algorithms’ operation in unexpected ways.

4 Identifying Roots of Algorithmic Progress

SoTA deep policy gradient methods are comprised of many interacting components. At what is generally described as their core, these methods incorporate mechanisms like trust region-enforcing steps, time-dependent value predictors, and advantage estimation methods for controlling the exploitation/exploration trade-off. However, these algorithms also incorporate many less oft-discussed(不常被讨论的)optimizations that ultimately dictate much of agent behavior. Given the need to improve on these algorithms, the fact that such optimizations are so important begs the question: how do we identify the true roots of algorithmic progress in deep policy gradient methods?

Unfortunately, we find that answering this question is not easy. Going back to our study of PPO and TRPO, it is widely believed (and claimed) that the key innovation of PPO responsible for its improved performance over the baseline of TRPO is the ratio clipping mechanism. However, we have already shown that this clipping mechanism does not enforce the KL region it is supposed to. Where is PPO’s improved performance coming from, then?

To address this question, we set out to disentangle(松开)the impact of PPO’s core clipping mechanism from its code-level optimizations. Specifically, we examine how employing the core PPO and TRPO steps changes model performance while controlling for the effect of code-level optimizations identified in standard implementations of PPO. (Note that these code-level optimizations are algorithm independent: they can be straightforwardly applied to any policy gradient method.) To account for the effects of these optimizations, we study an additional algorithm which we denote as TRPO+, consisting of the core algorithmic contribution of TRPO in combination with PPO’s code-level optimizations as identified in Section 2. We note that the four algorithms we study (PPO, PPO-M, TRPO, and TRPO+) now capture all combinations of core algorithms and code-level optimizations, allowing us to study the impact of each in a more fine-grained manner.

Our results show that code-level optimizations contribute to algorithms’ increased performance often significantly more than the choice of algorithm (i.e., using PPO vs. TRPO).

Given the relative insignificance of the step mechanism compared to the use of code-level optimizations, we are prompted to ask: to what extent is the clipping mechanism ofPPO even necessary? It turns out that the clipping mechanism is not at all necessary to achieve high performance — we find that PPO-NOCLIP achieves similar results to PPO in terms of benchmark performance without any clipping at all.

Our results suggest that it is difficult to attribute success to different aspects of policy gradient algorithms without careful analysis.

A Appendix

A.2 PPO Code-level Optimizations

A.2.1 Additional Optimizations

In addition to the optimizations listed in Section 2, PPO also uses the following optimizations:

-

Reward Clipping: The implementation also clips the rewards within a preset range (usually [−5, 5] or [−10, 10]).

-

Observation Normalization: In a similar manner to the rewards, the raw states are also not fed into the optimizer. Instead, the states are first normalized to mean-zero, variance-one vectors.

-

Observation Clipping: Analagously to rewards, the observations are also clipped within a range, usually [−10, 10].

-

Hyperbolic tan activations: Implementations of policy gradient algorithms can also use hyperbolic tangent function activations between layers in the policy and value networks.

-

Global Gradient Clipping: After computing the gradient with respect to the policy and the value networks, the implementation clips the gradients such the “global l2 norm” (i.e. the norm of the concatenated gradients of all parameters) does not exceed 0.5.