Paper 34: Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning (DQN2013)

Abstract

-

We present the first DL model to successfully learn control policies directly from high-dimensional sensory input using reinforcement learning.

-

The model is a CNN, trained with a variant of Q-learning, whose input is raw pixels and whose output is a value function estimating future rewards.

-

We apply our method to seven Atari 2600 games from the Arcade Learning Environment, with no adjustment of the architecture or learning algorithm.

1 Introduction

RL presents several challenges from a DL perspective.

-

Firstly, most successful DL applications to date have required large amounts of handlabelled training data. RL algorithms, on the other hand, must be able to learn from a scalar reward signal that is frequently sparse, noisy and delayed. The delay between actions and resulting rewards, which can be thousands of time-steps long, seems particularly daunting(令人生畏的)when compared to the direct association between inputs and targets found in supervised learning.

-

Another issue is that most DL algorithms assume the data samples to be independent, while in RL one typically encounters sequences of highly correlated states.

-

Furthermore, in RL the data distribution changes as the algorithm learns new behaviors, which can be problematic for DL methods that assume a fixed underlying distribution.

This paper demonstrates that a CNN can overcome these challenges to learn successful control policies from raw video data in complex RL environments. The network is trained with a variant of the Q-learning algorithm, with SGD to update the weights. To alleviate the problems of correlated data and non-stationary distributions, we use an experience replay mechanism which randomly samples previous transitions, and thereby smooths the training distribution over many past behaviors.

Our goal is to create a single neural network agent that is able to successfully learn to play as many of the games as possible. The network was not provided with any game-specific information or hand-designed visual features, and was not privy to the internal state of the emulator; it learned from nothing but the video input, the reward and terminal signals, and the set of possible actions - just as a human player would. Furthermore the network architecture and all hyperparameters used for training were kept constant across the games. So far the network has outperformed all previous RL algorithms on six of the seven games we have attempted and surpassed an expert human player on three of them.

4 Deep Reinforcement Learning

Our goal is to connect a RL algorithm to a DNN which operates directly on RGB images and efficiently process training data by using stochastic gradient updates.

Tesauro’s TD-Gammon architecture provides a starting point for such an approach. This architecture updates the parameters of a network that estimates the value function, directly from on-policy samples of experience, st, at, rt, st+1, at+1, drawn from the algorithm’s interactions with the environment (or by self-play, in the case of backgammon). Since this approach was able to outperform the best human backgammon players 20 years ago, it is natural to wonder whether two decades of hardware improvements, coupled with modern DNN architectures and scalable RL algorithms might produce significant progress.

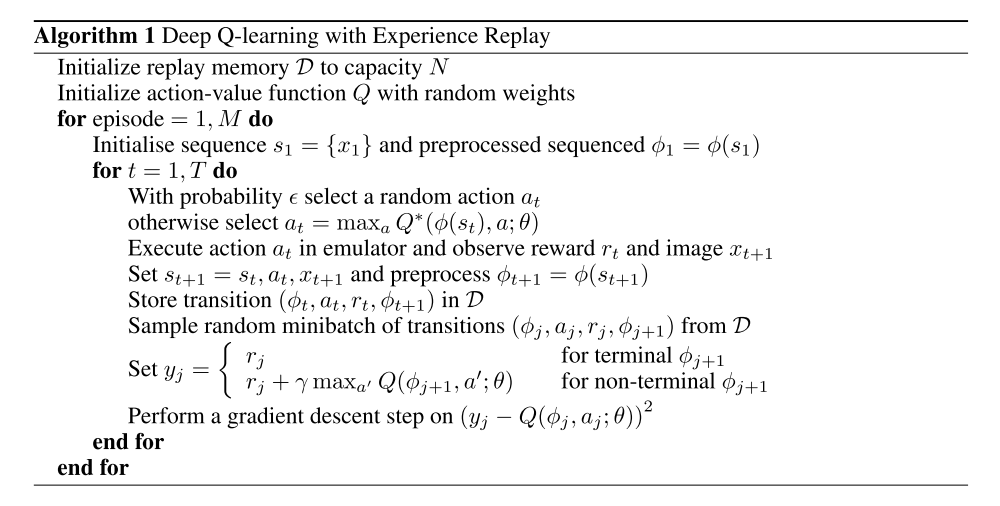

In contrast to TD-Gammon and similar online approaches, we utilize a technique known as experience replay where we store the agent’s experiences at each time-step, et = (st, at, rt, st+1) in a data-set D = e1, …, eN, pooled over many episodes into a replay memory. During the inner loop of the algorithm, we apply Q-learning updates, or minibatch updates, to samples of experience, e ∼ D, drawn at random from the pool of stored samples. After performing experience replay, the agent selects and executes an action according to an ε-greedy policy. Since using histories of arbitrary length as inputs to a neural network can be difficult, our Q-function instead works on fixed length representation of histories produced by a function φ. The full algorithm, which we call deep Q-learning, is presented in Algorithm 1.

This approach has several advantages over standard online Q-learning.

-

First, each step of experience is potentially used in many weight updates, which allows for greater data efficiency.

-

Second, learning directly from consecutive samples is inefficient, due to the strong correlations between the samples; randomizing the samples breaks these correlations and therefore reduces the variance of the updates.

-

Third, when learning on-policy the current parameters determine the next data sample that the parameters are trained on. It is easy to see how unwanted feedback loops may arise and the parameters could get stuck in a poor local minimum, or even diverge catastrophically. By using experience replay the behavior distribution is averaged over many of its previous states, smoothing out learning and avoiding oscillations or divergence in the parameters. Note that when learning by experience replay, it is necessary to learn off-policy (because our current parameters are different to those used to generate the sample), which motivates the choice of Q-learning.