Paper 35: Human-level Control through Deep Reinforcement Learning (DQN2015)

Abstract

Here we use recent advances in training DNNs to develop a novel artificial agent, termed a deep Q-network, that can learn successful policies directly from high-dimensional sensory inputs using end-to-end RL.

We tested this agent on the challenging domain of classic Atari 2600 games. We demonstrate that the deep Q-network agent, receiving only the pixels and the game score as inputs, was able to surpass the performance of all previous algorithms and achieve a level comparable to that of a professional human games tester across a set of 49 games, using the same algorithm, network architecture and hyperparameters. This work bridges the divide between high-dimensional sensory inputs and actions, resulting in the first artificial agent that is capable of learning to excel at a diverse array of challenging tasks.

Introduction

RL is known to be unstable or even to diverge when a nonlinear function approximator such as a neural network is used to represent the action-value (also known as Q) function. This instability has several causes:

-

the correlations present in the sequence of observations,

-

the fact that small updates to Q may significantly change the policy and therefore change the data distribution,

-

the correlations between the action-values (Q) and the target values.

We address these instabilities with a novel variant of Q-learning, which uses two key ideas.

-

First, we used a biologically inspired mechanism termed experience replay that randomizes over the data, thereby removing correlations in the observation sequence and smoothing over changes in the data distribution.

-

Second, we used an iterative update that adjusts the action-values (Q) towards target values that are only periodically updated, thereby reducing correlations with the target.

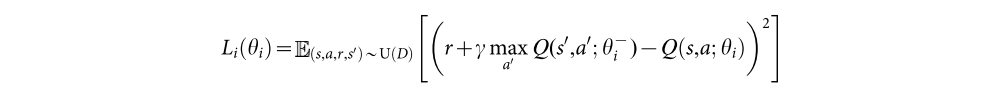

During learning, we apply Q-learning updates, on samples (or minibatches) of experience (s,a,r,s’) ~ U(D), drawn uniformly at random from the pool of stored samples. The Q-learning update at iteration i uses the following loss function:

The target network parameters are only updated with the Q-network parameters every C steps and are held fixed between individual updates.

Evaluation

We demonstrate the importance of the individual core components of the DQN agent - the replay memory, separate target Q-network and deep CNN architecture - by disabling them and demonstrating the detrimental(有害的)effects on performance.

Games demanding more temporally extended planning strategies still constitute a major challenge for all existing agents including DQN (for example, Montezuma’s Revenge).

Future Work

In the future, it will be important to explore the potential use of biasing the content of experience replay towards salient(突出的)events.

Methods

-

Preprocessing

Working directly with raw Atari 2600 frames, which are 210×160 pixel images with a 128-colour palette, can be demanding in terms of computation and memory requirements. We apply a basic preprocessing step aimed at reducing the input dimensionality and dealing with some artefacts of the Atari 2600 emulator.

-

First, to encode a single frame we take the maximum value for each pixel colour value over the frame being encoded and the previous frame. This was necessary to remove flickering that is present in games where some objects appear only in even frames while other objects appear only in odd frames, an artefact caused by the limited number of sprites Atari 2600 can display at once.

-

Second, we then extract the Y channel, also known as luminance, from the RGB frame and rescale it to 84×84. The function Φ from algorithm 1 described below applies this preprocessing to the m most recent frames and stacks them to produce the input to the Q-function, in which m=4, although the algorithm is robust to different values of m (for example, 3 or 5).

-

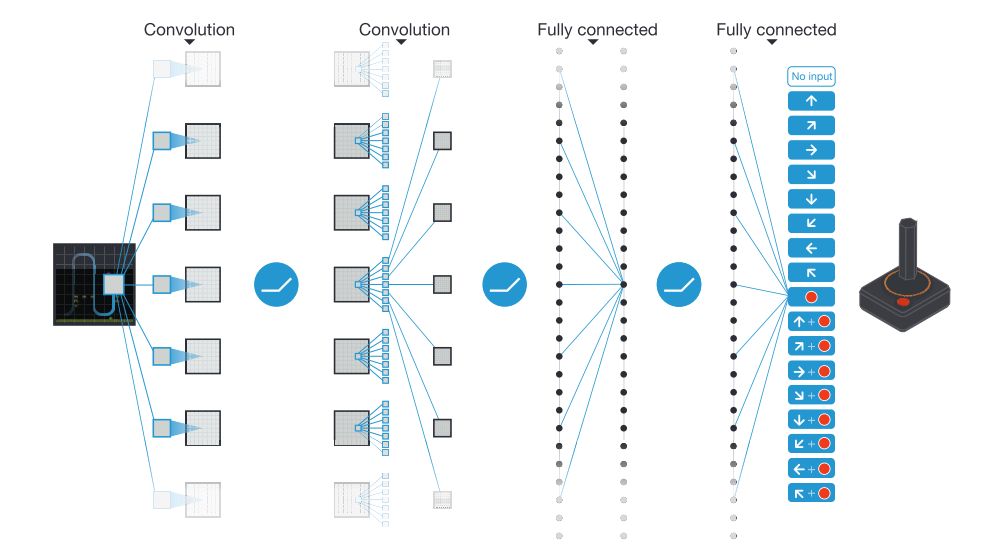

Model architecture

We use an architecture in which there is a separate output unit for each possible action, and only the state representation is an input to the neural network. The outputs correspond to the predicted Q-values of the individual actions for the input state. The main advantage of this type of architecture is the ability to compute Q-values for all possible actions in a given state with only a single forward pass through the network.

-

The exact architecture is as follows. The input to the neural network consists of an 84×84×4 image produced by the preprocessing map Φ. The first hidden layer convolves 32 filters of 8×8 with stride 4 with the input image and applies a rectifier nonlinearity. The second hidden layer convolves 64 filters of 4×4 with stride 2, again followed by a rectifier nonlinearity. This is followed by a third convolutional layer that convolves 64 filters of 3×3 with stride 1 followed by a rectifier. The final hidden layer is fully-connected and consists of 512 rectifier units. The output layer is a fully-connected linear layer with a single output for each valid action. The number of valid actions varied between 4 and 18 on the games we considered.

-

Training details

We performed experiments on 49 Atari 2600 games where results were available for all other comparable methods. A different network was trained on each game: the same network architecture, learning algorithm and hyperparameter settings were used across all games, showing that our approach is robust enough to work on a variety of games while incorporating only minimal prior knowledge. While we evaluated our agents on unmodified games, we made one change to the reward structure of the games during training only. As the scale of scores varies greatly from game to game, we clipped all positive rewards at 1 and all negative rewards at -1, leaving 0 rewards unchanged. Clipping the rewards in this manner limits the scale of the error derivatives and makes it easier to use the same learning rate across multiple games. At the same time, it could affect the performance of our agent since it cannot differentiate between rewards of different magnitude. For games where there is a life counter, the Atari 2600 emulator also sends the number of lives left in the game, which is then used to mark the end of an episode during training.

In these experiments, we used the RMSProp algorithm with minibatches of size 32. The behaviour policy during training was ε-greedy with ε annealed linearly from 1.0 to 0.1 over the first million frames, and fixed at 0.1 thereafter. We trained for a total of 50 million frames (that is, around 38 days of game experience in total) and used a replay memory of 1 million most recent frames.

Following previous approaches to playing Atari 2600 games,we also use a simple frame-skipping technique. More precisely, the agent sees and selects actions on every kth frame instead of every frame, and its last action is repeated on skipped frames. Because running the emulator forward for one step requires much less computation than having the agent select an action, this technique allows the agent to play roughly k times more games without significantly increasing the runtime. We use k=4 for all games.

The values of all the hyperparameters and optimization parameters were selected by performing an informal search on the games Pong, Breakout, Seaquest, Space Invaders and Beam Rider. We did not perform a systematic grid search owing to the high computational cost. These parameters were then held fixed across all other games. The values and descriptions of all hyperparameters are provided.

Our experimental setup amounts to using the following minimal prior knowledge: that the input data consisted of visual images (motivating our use of a convolutional deep network), the game-specific score (with no modification), number of actions, although not their correspondences (for example, specification of the up ‘button’) and the life count.

-

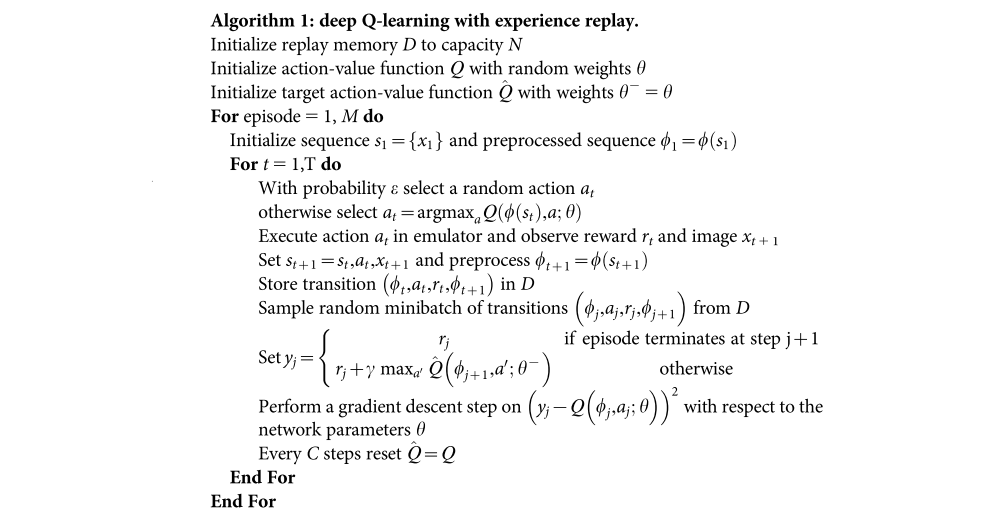

Training algorithm for deep Q-networks

The full algorithm for training deep Q-networks is presented in Algorithm 1. The algorithm modifies standard online Q-learning in two ways to make it suitable for training large neural networks without diverging.

-

experience replay

-

target network

We also found it helpful to clip the error term from the update to be between -1 and 1. Because the absolute value loss function |x| has a derivative of -1 for all negative values of x and a derivative of 1 for all positive values of x, clipping the squared error to be between -1 and 1 corresponds to using an absolute value loss function for errors outside of the (-1,1) interval. This form of error clipping further improved the stability of the algorithm.