Paper 37: Dota 2 with Large Scale Deep Reinforcement Learning (OpenAI Five) — Main Text

OpenAI Blog

Abstract

-

The game of Dota 2 presents novel challenges for AI systems such as long time horizons, imperfect information, and complex, continuous state-action spaces, all challenges which will become increasingly central to more capable AI systems.

-

OpenAI Five leveraged existing RL techniques, scaled to learn from batches of approximately 2 million frames every 2 seconds.

-

We developed a distributed training system and tools for continual training which allowed us to train OpenAI Five for 10 months.

-

OpenAI Five demonstrates that self-play RL can achieve superhuman performance on a difficult task.

1 Introduction

The key ingredient in solving this complex environment was to scale existing RL systems to unprecedented(空前的)levels, utilizing thousands of GPUs over multiple months. We built a distributed training system to do this which we used to train a Dota 2-playing agent called OpenAI Five.

One challenge we faced in training was that the environment and code continually changed as our project progressed. In order to train without restarting from the beginning after each change, we developed a collection of tools to resume(恢复)training with minimal loss in performance which we call surgery. Over the 10-month training process, we performed approximately one surgery per two weeks. These tools allowed us to make frequent improvements to our strongest agent within a shorter time than the typical practice of training from scratch would allow. As AI systems tackle larger and harder problems, further investigation of settings with ever-changing environments and iterative development will be critical.

2 Dota 2

To play Dota 2, an AI system must address various challenges:

-

Long time horizons. Dota 2 games run at 30 frames per second for approximately 45 minutes. OpenAI Five selects an action every fourth frame, yielding approximately 20,000 steps per episode. By comparison, chess usually lasts 80 moves, Go 150 move. -

Partially-observed state. Each team in the game can only see the portion of the game state near their units and buildings; the rest of the map is hidden. Strong play requires making inferences based on incomplete data, and modeling the opponent’s behavior. -

High-dimensional action and observation spaces. Dota 2 is played on a large map containing ten heroes, dozens of buildings, dozens of non-player units, and a long tail of game features such as runes, trees, and wards. OpenAI Five observes ∼ 16,000 total values (mostly floats and categorical values with hundreds of possibilities) each time step. We discretize the action space; on an average timestep our model chooses among 8,000 to 80,000 actions (depending on hero). For comparison Chess requires around one thousand values per observation (mostly 6-possibility categorical values) and Go around six thousand values (all binary). Chess has a branching factor of around 35 valid actions, and Go around 250.

Our system played Dota 2 with two limitations from the regular game:

-

Subset of 17 heroes— in the normal game players select before the game one from a pool of 117 heroes to play; we support 17 of them. -

No support for items which allow a player to temporarily control multiple units at the same time(Illusion Rune, Helm of the Dominator, Manta Style, and Necronomicon). We removed these to avoid the added technical complexity of enabling the agent to control multiple units.

3 Training System

3.1 Playing Dota using AI

We adopt the following framework to translate the vague(模糊的)problem of “play this complex game at a superhuman level” into a detailed objective suitable for optimization.

Although the Dota 2 engine runs at 30 frames per second, OpenAI Five only acts on every 4th frame which we call a timestep. Each timestep, OpenAI Five receives an observation from the game engine encoding all the information a human player would see such as units’ health, position, etc. OpenAI Five then returns a discrete action to the game engine, encoding a desired movement, attack, etc.

Some properties of the environment were randomized during training, including the heroes in the game and which items the heroes purchased. Sufficiently diverse training games are necessary to ensure robustness to the wide variety of strategies and situations that arise in games against human opponents.

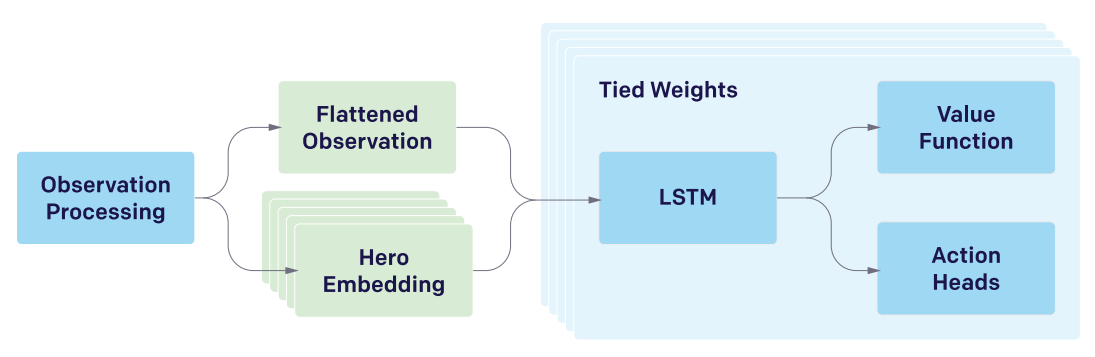

We define a policy (π) as a function from the history of observations to a probability distribution over actions, which we parameterize as a RNN with approximately 159 million parameters (θ). The neural network consists primarily of a single-layer 4096-unit LSTM (see Figure 1). Given a policy, we play games by repeatedly passing the current observation as input and sampling an action from the output distribution at each timestep.

Figure 1: Simplified OpenAI Five Model Architecture

Separate replicas of the same policy function (with identical parameters θ) are used to control each of the five heroes on the team. Because visible information and fog of war (area that is visible to players due to proximity of friendly units) are shared across a team in Dota 2, the observations are nearly identical for each hero.

Instead of using the pixels on the screen, we approximate the information available to a human player in a set of data arrays. This approximation is imperfect; there are small pieces of information which humans can gain access to which we have not encoded in the observations. On the flip side, while we were careful to ensure that all the information available to the model is also available to a human, the model does get to see all the information available simultaneously every time step, whereas a human needs to actively click to see various parts of the map and status modifiers. OpenAI Five uses this semantic observation space for two reasons:

-

First, because our goal is to study strategic planning and high-level decision-making rather than focus on visual processing.

-

Second, it is infeasible for us to render each frame to pixels in all training games; this would multiply the computation resources required for the project many-fold.

Although these discrepancies exist, we do not believe they introduce significant bias when benchmarking against human players. To allow the five networks to choose different actions, the LSTM receives an extra input from the observation processing, indicating which of the five heroes is being controlled.

3.2 Optimizing the Policy

Our goal is to find a policy which maximizes the probability of winning the game against professional human experts. In practice, we maximize a reward function which includes additional signals such as characters dying, collecting resources, etc. We also apply several techniques to exploit the zero-sum multi-player structure of the problem when computing the reward function — for example, we symmetrize(使均匀)rewards by subtracting the reward earned by the opposing team. We constructed the reward function once at the start of the project based on team members’ familiarity with the game. Although we made minor tweaks when game versions changed, we found that our initial choice of what to reward worked fairly well. The presence of these additional signals was important for successful training.

The policy is trained using PPO, a variant of advantage actor critic. The optimization algorithm uses GAE, a standard advantage-based variance reduction technique to stabilize and accelerate training. We train a network with a central, shared LSTM block, that feeds into separate fully connected layers producing policy and value function outputs.

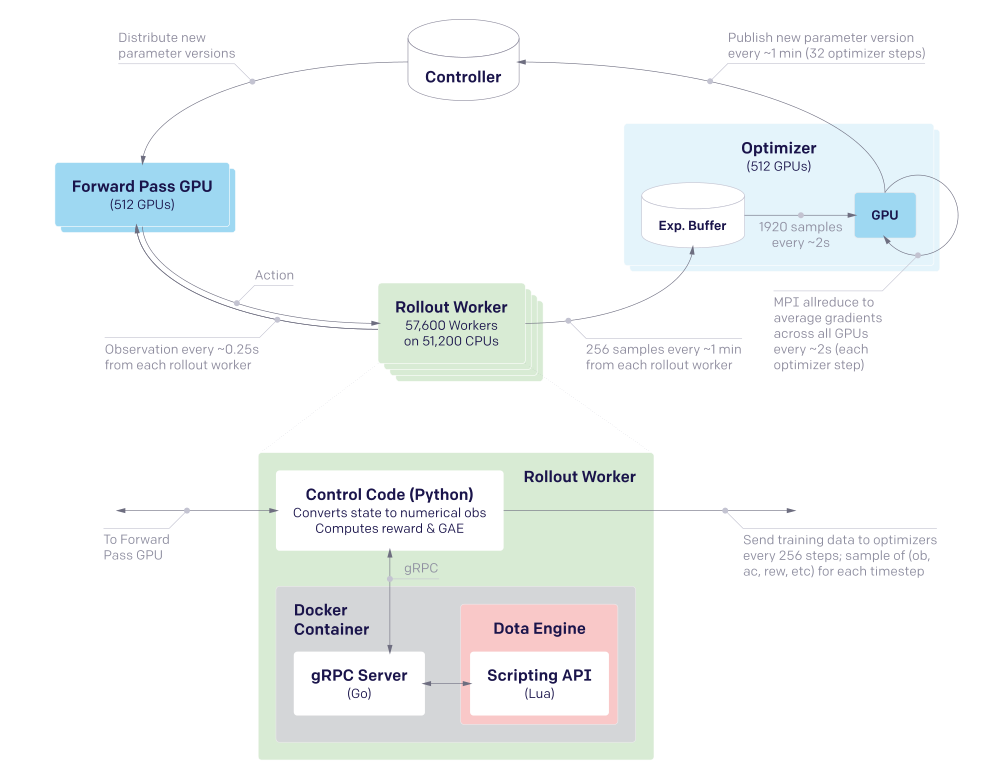

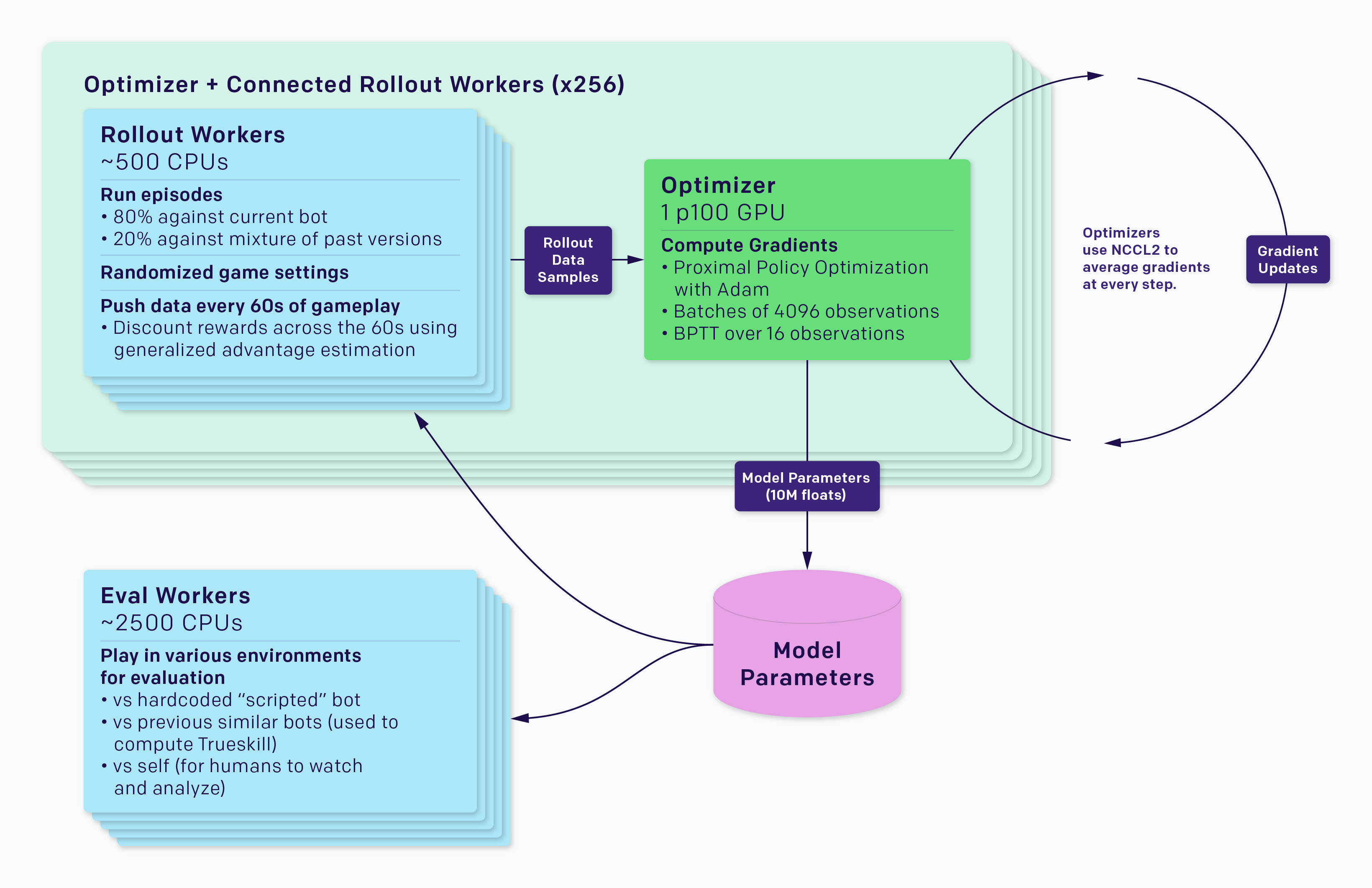

The training system is represented in Figure 2. We train our policy using collected self-play experience from playing Dota 2. A central pool of optimizer GPUs receives game data and stores it asynchronously in local buffers called experience buffers. Each optimizer GPU computes gradients using mini-batches sampled randomly from its experience buffer. Gradients are averaged across the pool using NCCL2 allreduce before being synchronously applied to the parameters. In this way the effective batch size is the batch size on each GPU (120 samples, each with 16 timesteps) multiplied by the number of GPUs (up to 1536 at the peak), for a total batch size of 2,949,120 time steps (each with five hero policy replicas).

We apply the Adam optimizer using truncated backpropagation through time over samples of 16 timesteps. Gradients are additionally clipped per parameter to be within between ±5√v where v is the running estimate of the second moment of the (unclipped) gradient. Every 32 gradient steps, the optimizers publish a new version of the parameters to a central Redis storage called the controller. The controller also stores all metadata about the state of the system, for stopping and restarting training runs.

“Rollout” worker machines run self-play games. They run these games at approximately 1/2 real time, because we found that we could run slightly more than twice as many games in parallel at this speed, increasing total throughput. We describe our integration with the Dota 2 engine in Appendix. They play the latest policy against itself for 80% of games, and play against older policies for 20% of games. The rollout machines run the game engine but not the policy; they communicate with a separate pool of GPU machines which run forward passes in larger batches of approximately 60. These machines frequently poll the controller to gather the newest parameters.

Rollout machines send data asynchronously from games that are in progress, instead of waiting for an entire game to finish before publishing data for optimization; the rollout data is aggregated. We have a discussion for the benefits of keeping the rollout-optimization loop tight. Because we use GAE with λ = 0.95, the GAE rewards need to be smoothed over a number of timesteps » 1/λ = 20; using 256 timesteps causes relatively little loss. For a full list of the hyperparameters used in training, see Appendix.

The entire system runs on our custom distributed training platform called Rapid (see Figure 3), running on Google Cloud Platform. We use ops from the blocksparse library for fast GPU training.

Figure 2: System Overview

Our training system consists of 4 primary types of machines. Rollouts run the Dota 2 game on CPUs. They communicate in a tight loop with Forward Pass GPUs, which sample actions from the policy given the current observation. Rollouts send their data to Optimizer GPUs, which perform gradient updates. The Optimizers publish the parameter versions to storage in the Controller, and the Forward Pass GPUs occasionally pull the latest parameter version. Machine numbers are for the Rerun experiment; OpenAI Five’s numbers fluctuated(波动)between this scale and approximately 3x larger.

Figure 3: Rapid Framework

3.3 Continual Transfer via Surgery

As the project progressed, our code and environment gradually changed for three different reasons:

-

As we experimented and learned, we implemented

changes to the training process(reward structure, observations, etc) or even to thearchitecture of the policy neural network. -

Over time we

expanded the set of game mechanicssupported by the agent’s action and observation spaces. These were not introduced gradually in an effort to build a perfect curriculum. Rather they were added incrementally as a consequence of following the standard engineering practice of building a system by starting simple and adding complexity piece by piece over time. -

From time to time, Valve publishes

a new Dota 2 versionincluding changes to the core game mechanics and the properties of heroes, items, maps, etc; to compare to human players our agent must play on the latest game version.

These changes can modify the shapes and sizes of the model’s layers, the semantic meaning of categorical observation values, etc. When these changes occur, most aspects of the old model are likely relevant in the new environment. But cherry-picking parts of the parameter vector to carry over is challenging and limits reproducibility. For these reasons training from scratch is the safe and common response to such changes.

However, training OpenAI Five was a multi-month process with high capital expenditure, motivating the need for methods that can persist models across domain and feature changes. It would have been prohibitive (in time and money) to train a fresh model to a high level of skill after each such change (approximately every two weeks).

Our approach, which we term “surgery”, can be viewed as a collection of tools to perform offline operations to the old model πθ to obtain a new model ˆπˆθ compatible with the new environment, which performs at the same level of skill even if the parameter vectors ˆθ and θ have different sizes and semantics. We then begin training in the new environment using ˆπˆθ. In the simplest case where the environment, observation, and action spaces did not change, our standard reduces to insisting that the new policy implements the same function from observed states to action probabilities as the old:

This case is a special case of Net2Net-style function preserving transformations. We have developed tools to implement Equation 1 exactly when possible (adding observations, expanding layers, and other situations), and approximately when the type of modification to the environment, observation space, or action space precludes satisfying it exactly. See Appendix for further discussion of surgery.

In the end, we performed over twenty surgeries (along with many unsuccessful surgery attempts) over the ten-month lifetime of OpenAI Five. Surgery enabled continuous training without loss in performance. We will discuss our experimental verification of this method.

4 Experiments and Evaluation

In order to utilize this level of compute effectively we had to scale up along three axes.

-

First, we used batch sizes of 1 to 3 million timesteps (grouped in unrolled LSTM windows of length 16).

-

Second, we used a model with over 150 million parameters.

-

Finally, OpenAI Five trained for 180 days (spread over 10 months of real time due to restarts and reverts). Compared AlphaGo, we use 50 to 150 times larger batch size, 20 times larger model, and 25 times longer training time. Simultaneous works in recent months have matched or slightly exceeded our scale.

4.1 Human Evaluation

While human evaluation is the ultimate goal, we also need to evaluate our agents continually during training in an automated way. We achieve this by comparing them to a pool of fixed reference agents with known skill using the TrueSkill rating system.

OpenAI Five’s “playstyle” is difficult to analyze rigorously (and is likely influenced by our shaped reward function) but we can discuss in broad terms the flavor of comments human players made to describe how our agent approached the game. Over the course of training, OpenAI Five developed a distinct style of play with noticeable similarities and differences to human playstyles.

4.2 Validating Surgery with Rerun

In order to validate the time and resources saved by our surgery method, we trained a second agent between May 18, 2019 and June 12, 2019, using only the final environment, model architecture, etc. This training run, called “Rerun”, did not go through a tortuous(曲折的)route of changing game rules, modifications to the neural network parameters, online experiments with hyperparameters, etc.

Learning how to continue long-running training without affecting final performance is a promising area for future work.

While surgery as currently conceived is far from perfect, with proper tooling it becomes a useful method for incorporating certain changes into long-running experiments without paying the cost of a restart for each.

4.3 Batch Size

Increasing the batch size in our case means two things:

-

first, using twice as many optimizer GPUs to optimize over the larger batch,

-

second, using twice as many rollout machines and forward pass GPUs to produce twice as many samples to feed the increased optimizer pool.

In practice we see less than the ideal linear speedup, but the speedup from increasing batch size is still noticeable and allows us to reach the result in less wall time.

Our results suggest that speedup is less than linear. However, we speculate(推测)that this may change later in training when the problem becomes more difficult. Also, given the relevant compute costs, in this ablation study(消融实验)we did not tune hyperparameters such as learning rate separately for each batch size.

4.4 Data Quality

One unusual feature of our task is the length of the games; each rollout can take up to two hours to complete. For this reason it is infeasible for us to optimize entirely on fully on-policy trajectories; if we waited to apply gradient updates for an entire rollout game to be played using the latest parameters, we could make only one update every two hours. Instead, our rollout workers and optimizers operate asynchronously: rollout workers download the latest parameters, play a small portion of the game, and upload data to the experience buffer, while optimizers continually sample from whatever data is present in the experience buffer to optimize.

Early on in the project, we had rollout workers collect full episodes before sending it to the optimizers and downloading new parameters. This means that once the data finally enters the optimizers, it can be several hours old, corresponding to thousands of gradient steps. Gradients computed from these old parameters were often useless or destructive. In the final system rollout workers send data to optimizers after only 256 timesteps, but even so this can be a problem.

We found it useful to define a metric for this called staleness(陈旧). If a sample was generated by parameter version N and we are now optimizing version M, then we define the staleness of that data to be M − N. We see that increasing staleness by ∼ 8 versions causes significant slowdowns. Note that this level of staleness corresponds to a few minutes in a multi-month experiment. Our final system design targeted a staleness between 0 and 1 by sending game data every 30 seconds of gameplay and updating to fresh parameters approximately once a minute, making the loop faster than the time it takes the optimizers to process a single batch (32 PPO gradient steps). Because of the high impact of staleness, in future work it may be worth investigating whether optimization methods more robust to off-policy data could provide significant improvement in our asynchronous data collection regime.

Because optimizers sample from an experience buffer, the same piece of data can be re-used many times. If data is reused too often, it can lead to overfitting on the reused data. To diagnose this, we defined a metric called the sample reuse of the experiment as the instantaneous ratio between the rate of optimizers consuming data and rollouts producing data. If optimizers are consuming samples twice as fast as rollouts are producing them, then on average each sample is being used twice and we say that the sample reuse is 2. We see that reusing the same data even 2-3 times can cause a factor of two slowdown, and reusing it 8 times may prevent the learning of a competent policy altogether. Our final system targets sample reuse ∼ 1 in all our experiments.

These experiments on the early part of training indicate that high quality data matters even more than compute consumed; small degradation(退化)in data quality have severe effects on learning.

4.5 Long term credit assignment

Dota 2 has extremely long time dependencies. Where many RL environment episodes last hundreds of steps, games of Dota 2 can last for tens of thousands of time steps. Agents must execute plans that play out over many minutes, corresponding to thousands of timesteps. This makes our experiment a unique platform to test the ability of these algorithms to understand long-term credit assignment.

We study the time horizon over which our agent discounts rewards, defined as