Paper 37: Dota 2 with Large Scale Deep Reinforcement Learning (OpenAI Five) — Appendix

A Compute Usage

B Surgery

-

Changing the architecture

-

Changing the Observation Space

-

Changing the Environment or Action Space

-

Removing Model Parts

-

Smooth Training Restart

-

Benefits of Surgery

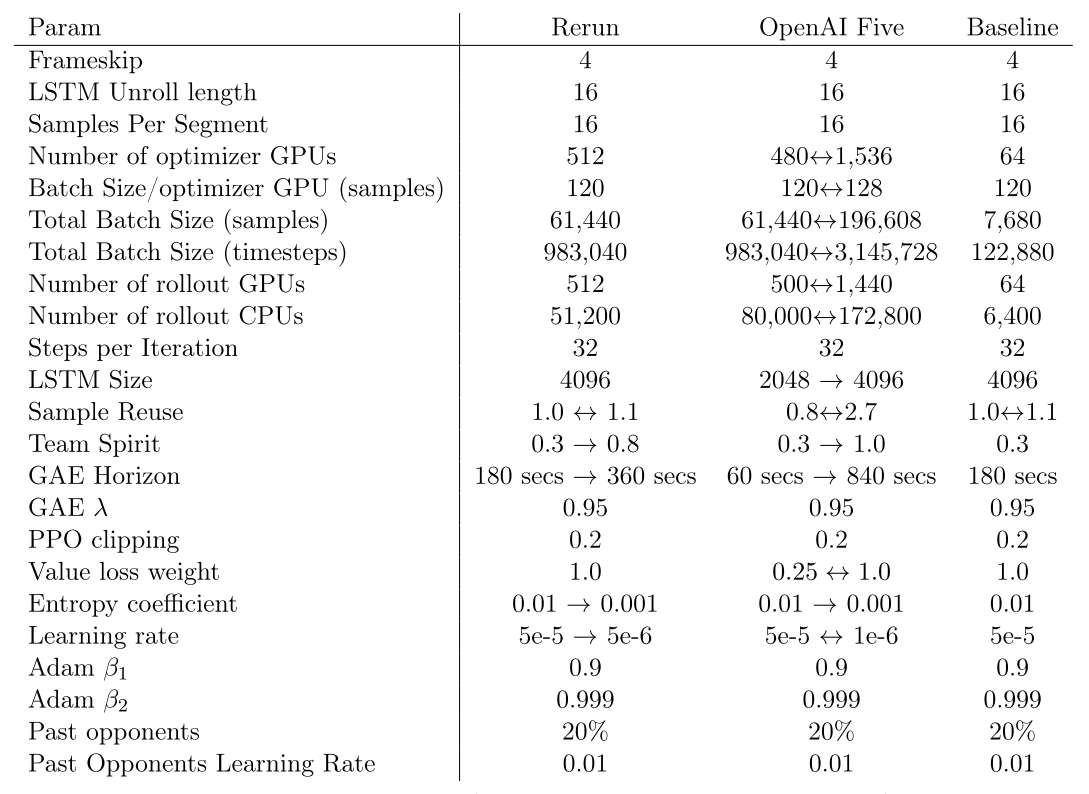

C Hyperparameters

When we ran Rerun we simplified the hyperparameter schedule based on the lessons we had learned. In the end we made changes to only four key hyperparameters:

-

Learning Rate

-

Entropy penalty coefficient

-

Team Spirit

-

GAE time horizon

Figure 1: Hyperparameters

D Evaluating agents’ understanding

It is often difficult to infer the intentions of an RL agent. Some actions are obviously useful — hitting an enemy that is low on health, or freezing them as they’re trying to escape — but many other decisions can be less obvious. This is tightly coupled with questions on intentionality(意向性): does our agent plan on attacking the tower, or doe it opportunistically deal the most damage possible in next few seconds?

To assess this, we attempt to predict future state of various features of the game from agent’s

-

Win probability: Binary label of either 0 or 1 at the end of the game. -

Net worth rank(净值排名): Which rank among the team (1-5) in terms of total resources collected will this hero be at the end of the game? This prediction is used by scripted item-buying logic to decide which agents buy items shared by the team such as wards. In human play (which the scripted logic is based on) this task is traditionally performed by heroes who will have the lowest net worth at the end of the game. -

Team objectives / enemy buildings: whether this hero will help the team destroy a given enemy building in the near future.

We added small networks of fully-connected layers that transform LSTM output into predictions of these values. For historical reasons, win probability passes gradients to the main LSTM and rest of the agent with a very small weight; the other auxiliary(辅助的)predictions use Tensorflow’s stop_gradient method to train on their own.

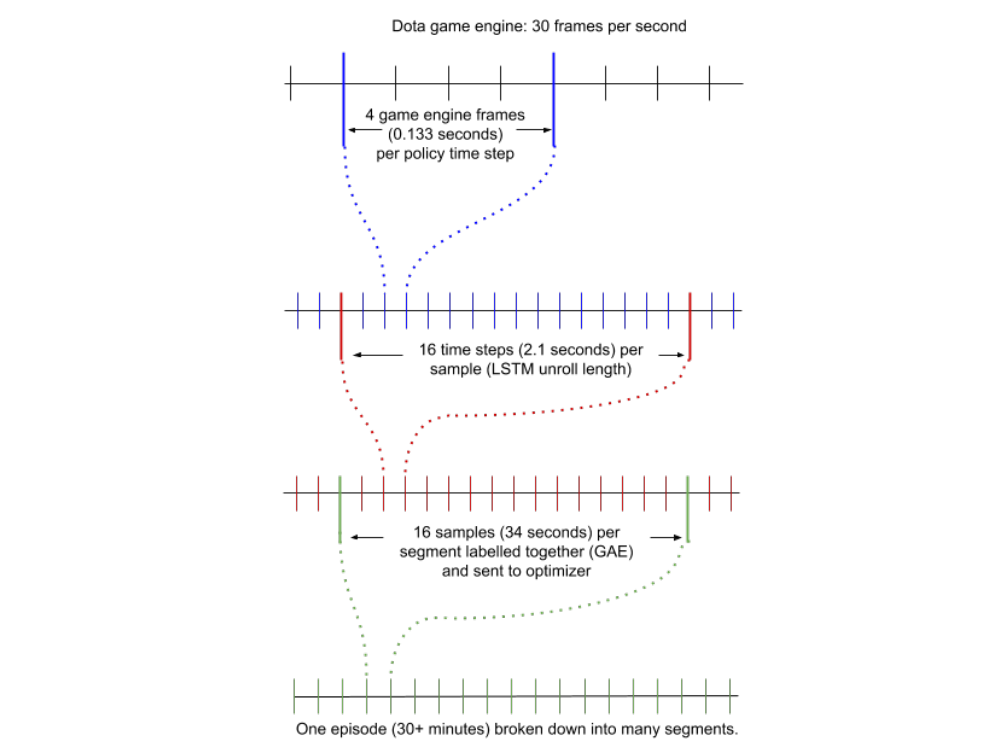

Figure 2: Timescales and Staleness

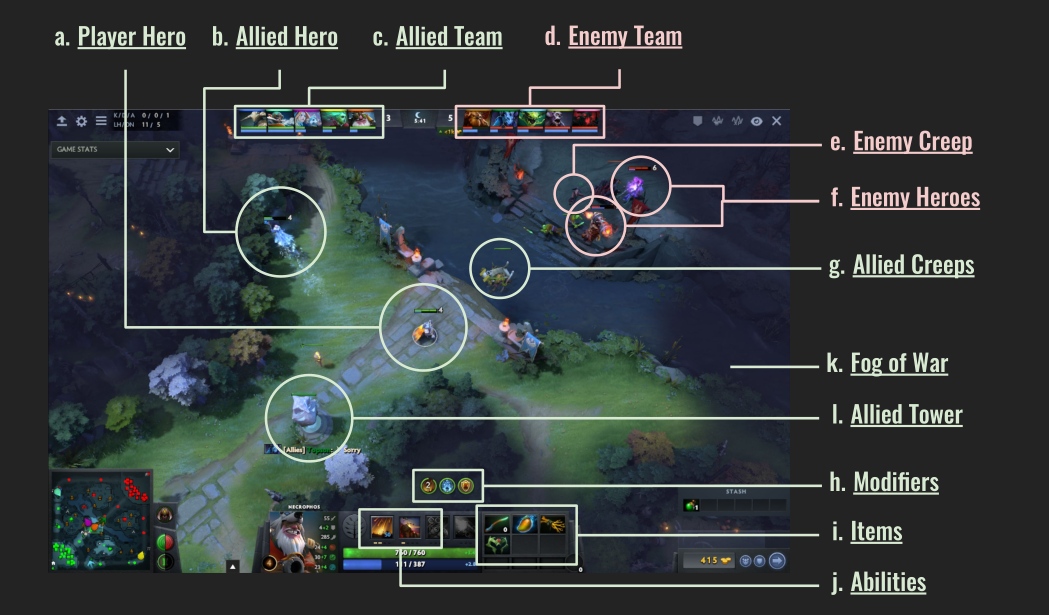

One difficulty in training these predictors is that we train our agent on 30-second segments of the game (see Figure 2), and any given 30-second snippet may not contain the ground truth (e.g. for win probability and networth position, we only have ground truth on the very last segment of the game). We address this by training these heads in a similar fashion to how we train value functions. If a segment contains the ground truth label, we use the ground truth label for all time steps in that segment; if not, we use the model’s prediction at the end of the segment as the label. For win probability, for example, more precisely the label y for a segment from time t1 to t2 is given by:

Where ˆy(t2) is is the model’s predicted win probability at the end of the segment. Although this requires information to travel backward through the game, we find it trains these heads to a degree of calibration and accuracy. For the team objectives, we are additionally interested in whether the event will happen soon.

For these we apply an additional discount factor with horizon of 2 minutes. This means that the enemy building predictions are not calibrated probabilities, but rather probabilities discounted by the expected time to the event.

D.1 Understanding OpenAI Five Finals

We explore the progression of win probability predictions over the course of training Rerun, illustrating the evolution of understanding. Version 5,000 of the agent (early in the training process and low performance) already has a sense of what situations in the game may lead to eventual win. The prediction continues to get better and better as training proceeds. This matches human performance at this task, where even spectators with relatively little gameplay experience can estimate who is ahead based on simple heuristics, but with more gameplay practice human experts can estimate the winner more and more accurately.

We also looked at heroes participation in destroying objectives. We can see different heroes’ predictions for each of the objectives in the game. In several cases all heroes predict they will participate in the attack (and they do). In few cases one or two heroes are left out, and indeed by watching the game replay we see that those heroes are busy in the different part of the map during that time. We illustrate these predictions with more details for two of the events. Predictions should not be read as calibrated probabilities, because they are trained with a discount factor.

D.2 Hero selection

In the normal game of Dota 2, two teams at the beginning of the game go through the process of selecting heroes. This is a very important step for future strategy, as heroes have different skill sets and special abilities. OpenAI Five is trained purely on learning to play the best game of Dota 2 possible given randomly selected heroes.

Although we could likely train a separate drafting agent to play the draft phase, we do not need to; instead we can use the win probability predictor. Because the main varying observation that agents see at the start of the game is which heroes are on each team, the win probability at the start of the game estimates the strength of a given matchup. Because there are only 4,900,896 combinations of two 5-hero teams from the pool of 17 heroes, we can precompute agent’s predicted win probability from the first few frames of every lineup. Given these precomputed win probabilities, we apply a dynamic programming algorithm to draft the best hero available on each turn.

In addition to building a hero selection tool, we also learned about our agent’s preferences from this. In many ways OpenAI Five’s preferences match human player’s preferences such as placing a high value (within this pool) on the hero Sniper. In other ways it does not agree with typical human knowledge, for example it places low value on Earthshaker. Our agent had trouble dealing with geometry of this hero’s “Fissure” skill, making this hero worse than others in training rollouts.

Another interesting tidbit(趣闻) is that at the very start of the draft, before any heroes are picked, OpenAI Five believes that the Radiant team has a 54% win chance (if picking first in the draft) or 53% (if picking second). Our agent’s higher estimate for the Radiant side over the Dire agrees with conventional wisdom within the Dota 2 community. Of course, this likely depends on the set of heroes available.

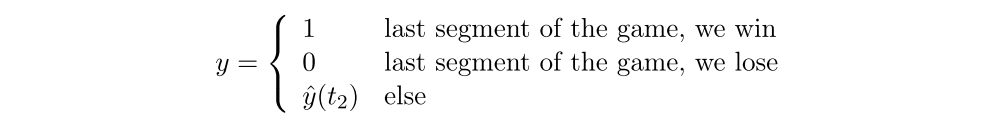

E Observation Space

At each time step one of our heroes observes ∼ 16,000 inputs about the game state (mostly real numbers with some integer categorical data as well).

Instead of using the pixels on the screen, we approximate the information available to a human player in a set of data arrays. This approximation is imperfect; there are small pieces of information which humans can gain access to which we have not encoded in the observations. On the flip side, while we were careful to ensure that all the information available to the model is also available to a human, the model does get to see all the information available simultaneously every time step, whereas a human needs to click into various menus and options to get that data. Although these discrepancies are a limitation, we do not believe they meaningfully detract from our ability to benchmark against human players.

Humans observe the game via a rendered screen, depicted in Figure 3. OpenAI Five uses a more semantic observation space than this for two reasons:

-

First, because our goal is to study strategic planning and gameplay rather than focus on visual processing.

-

Second, it is infeasible for us to render each frame to pixels in all training games; this would multiply the computation resources required for the project manyfold.

Figure 3: Dota 2’s human “Observation Space”

All float observations (including booleans which are treated as floats that happen to take values 0 or 1) are normalized before feeding into the neural network. For each observation, we keep a running mean and standard deviation of all data ever observed; at each timestep we subtract the mean and divide by the st dev, clipping the final result to be within (-5, 5).

F Action Space

Dota 2 is usually controlled using a mouse and keyboard. The majority of the actions involve a high-level command (attack, use a certain spell, or activate a certain item), along with a target (which might be an enemy unit for an attack, or a spot on the map for a movement). For that reason we represent the action our agent can choose at each timestep as a single primary action along with a number of parameter actions.

The number of primary actions available varies from time step to time step, averaging 8.1 in the games against OG. The primary actions available at a given time include universal actions like noop, move, attack, and others; use or activate one of the hero’s spells; use or activate one of the hero’s items; situational actions such as Buyback (if dead), Shrine (if near a shrine), or Purchase (if near a shop); and more. For many of the actions we wrote simple action filters, which determine whether the action is available; these check if there is a valid target nearby, if the ability/item is on cooldown, etc. At each timestep we restrict the set of available actions using these filters and present the final choices to the model.

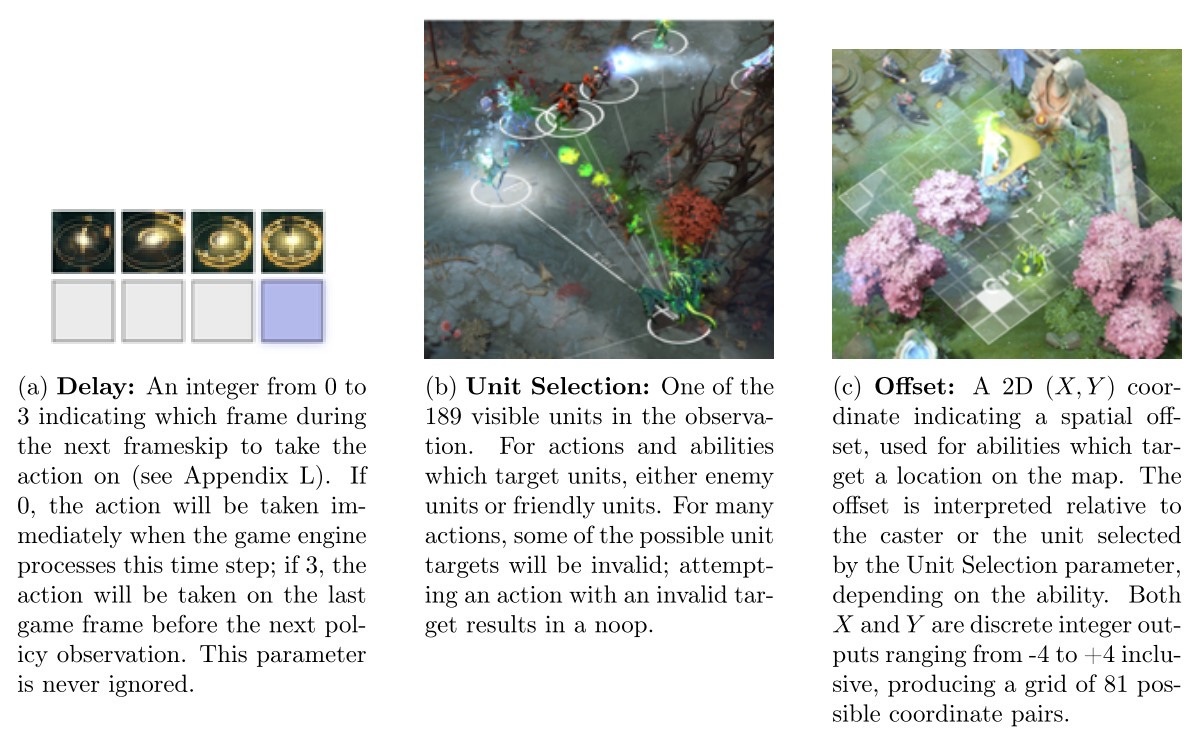

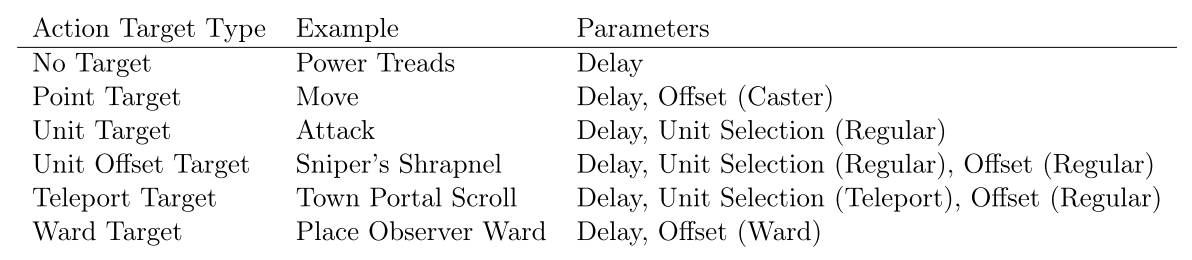

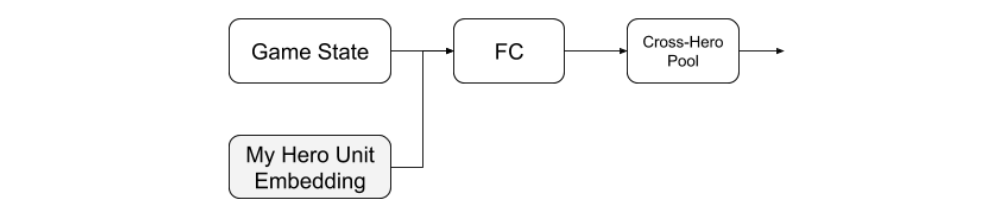

In addition to a primary action, the model chooses action parameters. At each timestep the model outputs a value for each of them; depending on the primary action, some of them are read and others ignored (when optimizing, we mask out the ignored ones since their gradients would be pure noise). There are 3 parameter outputs, Delay (4 dim), unit selection (189 dim), and offset (81 dim), described in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Action Parameters

All together this produces a combined factorized action space size of up to 30 × 4 × 189 × 81 = 1, 837, 080 dimensions (30 being the maximum number of primary actions we support). This number ignores the fact that the number of primary actions is usually much lower; some parameters are masked depending on the primary action; and some parameter combinations are invalid and those actions are treated as no-ops.

The average number of available actions varies significantly across heroes, as different heroes have different numbers spells and items with larger parameter counts. Across the two games played against Team OG, the average number of actions for a hero varied from 8,000 to 80,000.

Unit Selection and Offset are actually implemented within the model as several different, mutually exclusive parameters depending on the primary action. For Unit Selection, we found that using a single output head caused that head to learn very well to target tactical spells and abilities. One ability called “teleport,” however, is significantly different from all the others — rather than being used in a tactical fight, it is used to strategically reposition units across the map. Because the action is much more rare, the learning signal for targeting this ability would be drowned out(淹没)if we used a single model output head for both. For this reason the model outputs a normal Unit Selection parameter and a separate Teleport Selection parameter, and one or the other is used depending on the primary action. Similarly, the Offset parameter is split into “Regular Offset,” “Caster Offset” (for actions which only make sense offset from the caster), and “Ward Placement Offset” (for the rare action of placing observer wards).

We categorize all primary actions into 6 “Action target types” which determines which parameters the action uses, listed in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Action Target Types

F.1 Scripted Actions

Not all actions that a human takes in a game of Dota 2 are controlled by our RL agent. Some of the actions are scripted, meaning that we have written a rudimentary(基本的)rules-based system to handle these decisions. Most of these are for historical reasons — at the start of the project we gave the model control over a small set of the actions, and we gradually expanded it over time. Each additional action that we remove from the scripted logic and hand to the model’s control gives the RL system a higher potential skill cap, but comes with an cost measured in engineering effort to set it up and risks associated with learning and exploration. Indeed even when adding these new actions gradually and systematically, we occasionally encountered instabilities; for example the agent might quickly learn never to take a new action (and thus fail to explore the small fraction of circumstances where that action helps), and thus moreover fail to learn (or unlearn) the dependent parts of the gameplay which require competent use of the new action.

In the end there were still several systems that we had not yet removed from the scripted logic by the time the agent reached superhuman performance. While we believe the agent could ultimately perform better if these actions were not scripted, we saw no reason to do remove the scripting because superhuman performance had already been achieved. The full set of remaining scripted actions is:

-

Ability Builds(技能加点)

-

Item Purchasing(商店购物)

-

Item Swap(商品切换)

-

Courier Control(控制信使)

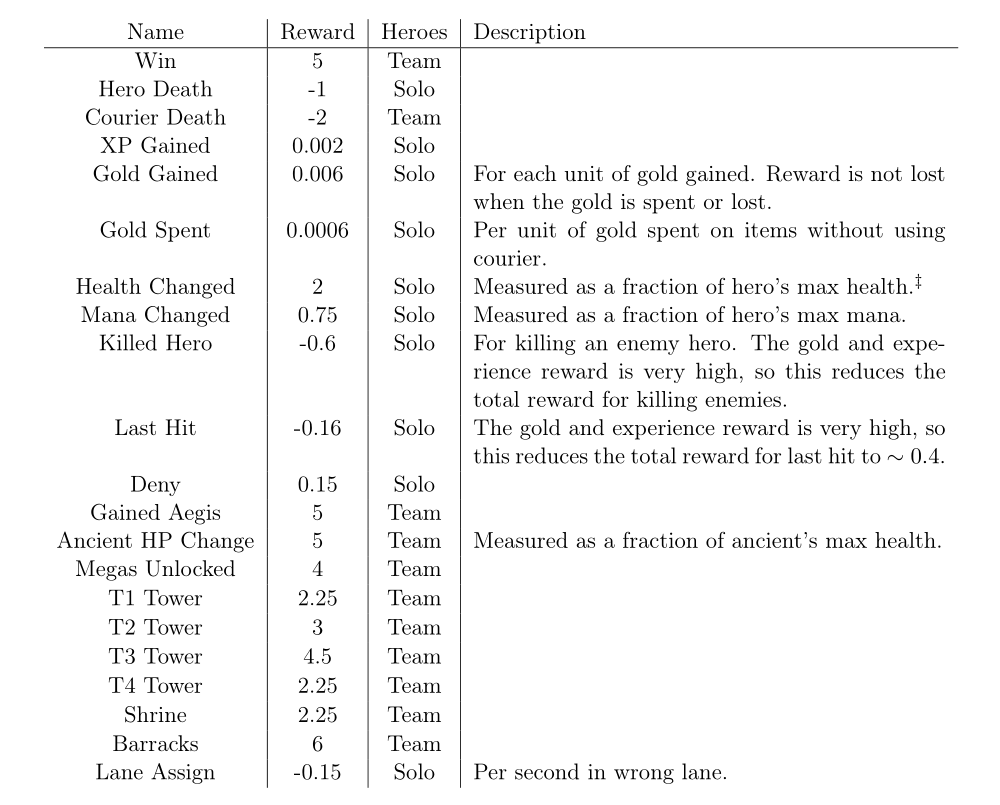

G Reward Weights

Our agent’s ultimate goal is to win the game. In order to simplify the credit assignment problem (the task of figuring out which of the many actions the agent took during the game led to the final positive or negative reward), we use a more detailed reward function. Our shaped reward is modeled loosely after potential-based shaping functions, though the guarantees therein do not apply here. We give the agent reward (or penalty) for a set of actions which humans playing the game generally agree to be good (gaining resources, killing enemies, etc).

All the results that we reward can be found in Figure 6, with the amount of the reward. Some are given to every hero on the team (“Team”) and some just to the hero who took the action “Solo”. Note that this means that when team spirit is 1.0, the total amount of reward is five times higher for “Team” rewards than “Solo” rewards.

Figure 6: Shaped Reward Weights

In addition to the set of actions rewarded and their weights, our reward function contains 3 other pieces:

-

Zero sum: The game is zero sum (only one team can win), everything that benefits one team necessarily hurts the other team. We ensure that all our rewards are zero-sum, bysubtracting from each hero’s reward the average of the enemies’ rewards. -

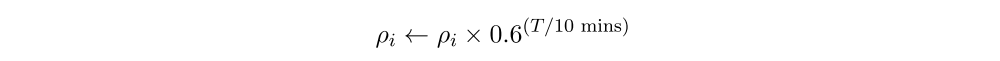

Game time weighting: Each player’s “power” increases dramatically over the course of a game of Dota 2. A character who struggled to kill a single weak creep early in the game can often kill many at once with a single stroke by the end of the game. This means that the end of the game simply produces more rewards in total (positive or negative). If we do not account for this, the learning procedure focuses entirely on the later stages of the game and ignores the earlier stages because they have less total reward magnitude. We use a simple renormalization to deal with this, multiplying all rewards other than the win/loss reward by a factor which decays exponentially over the course of the game.Each reward ρi earned a time T since the game began is scaled:

-

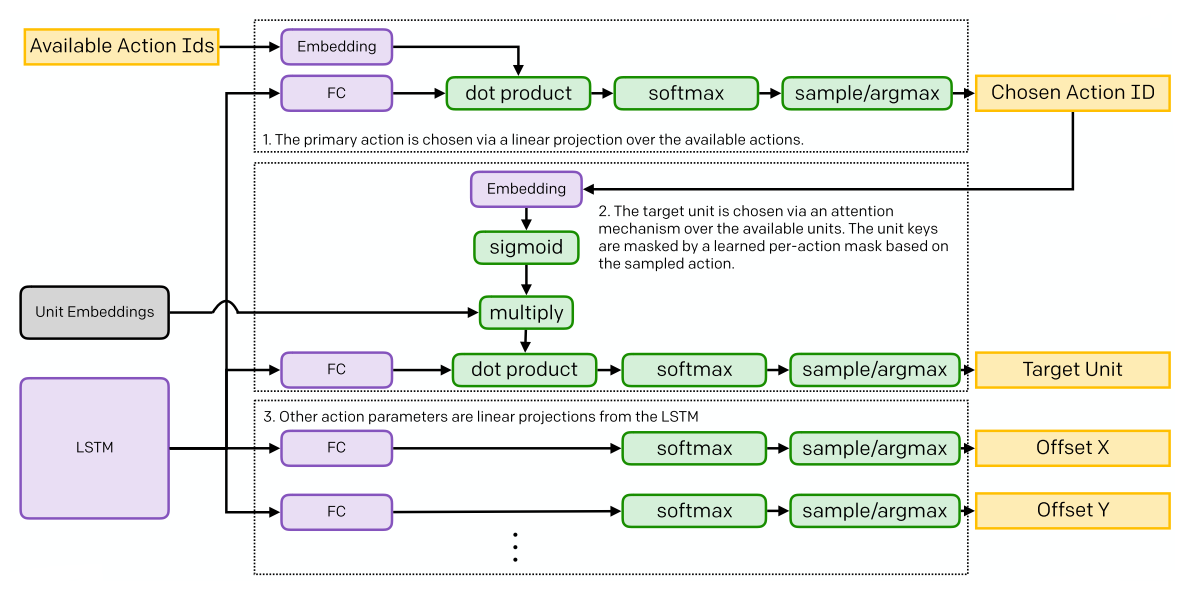

Team Spirit: Because we have multiple agents on one team, we have an additional dimension to the credit assignment problem, where the agents need learn which of the five agent’s behavior cause some positive outcome. The partial rewards defined in Figure 6 are an attempt to make the credit assignment easier, but they may backfire(回火)and in fact add more variance if an agent receives reward when a different agent takes a good action. To attempt dealing with this, we have introduced team spirit. Itmeasures how much agents on the team share in the spoils(战利品)of their teammates. If each hero earns raw individual reward ρi, then we compute the hero’s final reward ri as follows:

If team spirit is 0, then it’s every hero for themselves; each hero only receives reward for their own actions ri = ρi. If team spirit is 1, then every reward is split equally among all five heroes; ri = ρ. For a team spirit τ in between, team spirit-adjusted rewards are linearly interpolated between the two.

Ultimately we care about optimizing for team spirit τ = 1; we want the actions to be chosen to optimize the success of the entire team. However we find that lower team spirit reduces gradient variance in early training, ensuring that agents receive clearer reward for advancing their mechanical and tactical ability to participate in fights individually.

H Neural Network Architecture

OpenAI Five Model Architecture

A simplified diagram of the joint policy and value network is shown in the main text in Figure 1 (Part 1). The combined policy + value network uses 158,502,815 parameters (in the final version). The policy network is designed to receive observations from our bot-API observation space, and interact with the game using a rich factorized action space. These structured observation and action spaces heavily inform the neural network architecture used. We use five replica neural networks, each responsible for the observations and actions of one of the heroes in the team. At a high level, this network consists of three parts:

-

first the observations are processed and pooled into a single vector summarizing the state (see Figure 7 and Figure 8),

-

then that is processed by a single-layer large LSTM,

-

then the outputs of that LSTM are projected to produce outputs using linear projections (see Figure 9).

To provide the full details, we should clarify that Figure 1 in Part 1 is a slight over-simplification in three ways:

-

In practice the Observation Processing portion of the model is also cloned 5 times for the five different heroes. The weights are identical and the observations are nearly identical — but there are a handful of derived features which are different for each replica (such as “distance to me” for each unit). Thus the five replicas produce nearly identical, but perhaps not entirely identical, LSTM inputs. These non-identical features form a small portion of the observation space, and were not ablated; it is possible that they are not needed at all.

-

The “Flattened Observation” and “Hero Embedding” are processed before being sent into the LSTM (see Figure 8) by a fully-connected layer and a “cross-hero pool” operation, to ensure that the non-identical observations can be used by other members of the team if needed.

-

The “Unit Embeddings” from the observation processing are carried along beside the LSTM, and used by the action heads to choose a unit to target (see Figure 9).

In addition to the action logits, the value function is computed as another linear projection of the LSTM state. Thus our value function and action policy share a network and share gradients.

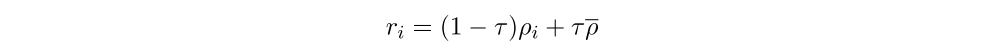

Figure 7: Flattening the observation space

First we process the complicated observation space into a single vector. The observation space has a tree structure; the full game state has various attributes such as global continuous data and a set of allied heroes. Each allied hero in turn has a set of abilities, a set of modifiers, etc. We process each node in the tree according to its data type. For example for spatial data, we concatenate the data within each cell and then apply a 2 layer conv net. For unordered sets, a common feature of our observations, we use a “Process Set” module. Weights in the Process Set module for processing abilities/items/modifiers are shared across allied and enemy heroes; weights for processing modifiers are shared across allied/enemy/neutral nonheroes. In addition to the main Game State observation, we extract the the Unit Embeddings from the “embedding output” of the units’ process sets, for use in the output (see Figure 9).

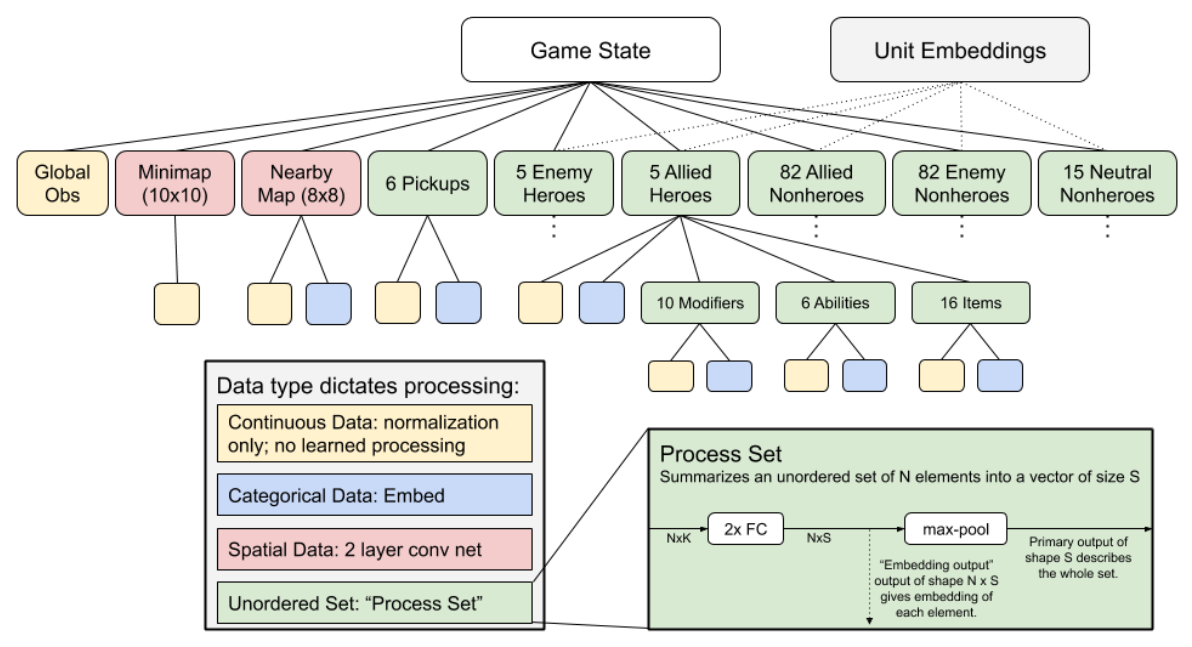

Figure 8: Preparing for LSTM

In order to tell each LSTM which of the team’s heroes it controls, we append the controlled hero’s Unit Embedding from the Unit Embeddings output of Figure 7 to thse Game State vector. Almost all of the inputs are the same for each of the five replica LSTMs (the only differences are the nearby map, previous action, and a very small fraction of the observations for each unit). In order to allow each replica to respond to the non-identical inputs of other replicas if needed, we add a “cross-hero pool” operation, in which we maxpool the first 25% of the vector across the five replica networks.

Figure 9: The hidden state of the LSTM and unit embeddings are used to parameterize the actions.

I Human Games

J TrueSkill: Evaluating a Dota 2 Agent Automatically

K Dota 2 Gym Environment

K.1 Data flow between the training environment and Dota 2

Dota 2 includes a scripting API designed for building bots. The provided API is exposed through Lua and has methods for querying the visible state of the game as well as submitting actions for bots to take. Parts of the map that are out of sight are considered to be in the fog of war and cannot be queried through the scripting API, which prevents us from accidentally “cheating” by observing anything a human player would not be able to see.

We designed our Dota 2 environment to behave like a standard OpenAI Gym environment. This standard respects an API contract where a step method takes action parameters and returns an observation from the next state of the environment. To send actions to Dota 2, we implemented a helper process in Go that we load into Dota 2 through an attached debugger that exposes a gRPC server. This gRPC server implements methods to configure a game and perform an environment step. By running the game with an embedded server, we are able to communicate with it over the network from any remote process.

When the step method is called in the gRPC server, it gets dispatched to the Lua code and then the method blocks until an observation arrives back from Lua to be returned to the caller. In parallel, the Dota 2 engine runs our Lua code on every step, sending the current game state observation to the gRPC server and waiting for it to return the current action. The game blocks until an action is available. These two parallel processes end up meeting in the middle, exchanging actions from gRPC in return for observations from Lua. Go was chosen to make this architecture easy to implement through its channels feature.

Putting the game environment behind a gRPC server allowed us to package the game into a Docker image and easily run many isolated game instances per machine. It also allowed us to easily setup, reset, and use the environment from anywhere where Docker is running. This design choice significantly improved researcher productivity when iterating on and debugging this system.

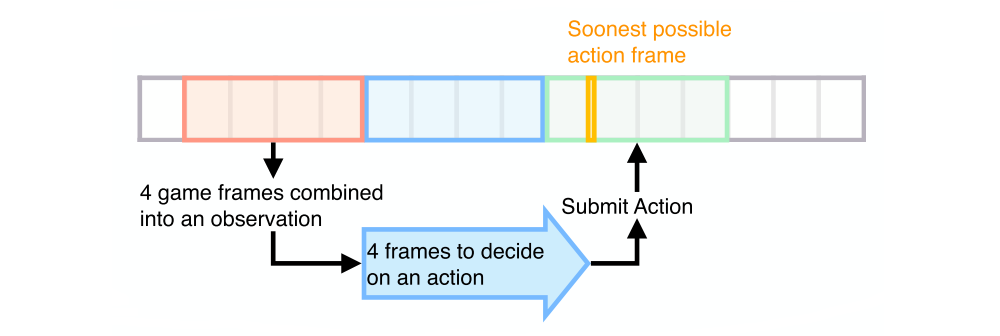

L Reaction time

The Dota 2 game engine runs at 30 steps per second so in theory a bot could submit an action every 33ms. Both to speed up our game execution and in order to bring reactions of our model closer to the human scale we downsample to every 4th frame, which we call frameskip. This yields an effective observation and action rate of 7.5 frames per second. To allow the model to take precisely timed actions, the action space includes a “delay” which indicates which frame during the frameskip the model wants this action to evaluate on. Thus the model can still take actions at a particular frame if so desired, although in practice we found that the model did not learn to do this and simply taking the action at the start of the frameskip was better.

Moreover, we reduce our computational requirements by allowing the game and the ML model to run concurrently by asynchronously issuing actions with an action offset. When the model receives an observation at time T, rather than making the game engine wait for the model to produce an action at time T, we let the game engine carry on running until it produces an observation at time T+1. The game engine then sends the observation at time T+1 to the model, and by this time the model has produced its action choice based on the observation at time T. In this way the action which the model takes at time T+1 is based upon the observation at time T. In exchange for this penalty in available “reaction time,” we are able to utilize our compute resources much more efficiently by preventing the two major computations from blocking one another (see Figure 10).

Taken together, these effects mean that the agent can react to new information with a reaction time randomly distributed between 5 and 8 frames (167ms to 267ms), depending on when during the frameskip the new information happens to occur. For comparison, human reaction time has been measured at 250ms in controlled experimental settings. This is likely an underestimate of reaction time during a Dota game.

Figure 10: Reaction Time

OpenAI Five observes four frames bundled together, so any surprising new information will become available at a random frame in the red region. The model then processes the observation in parallel while the game engine runs forward four more frames. The soonest it can submit an action based on the red observations is marked in yellow. This is between 5 and 8 frames (167-267ms) after the surprising event.

M Scale and Data Quality Ablation Details

M.1 Batch Size

In this section we demonstrate how large batch-sizes affect optimization time.

M.2 Sample Quality — Staleness

Staleness negatively affects speed of training, and the drop can be quite severe when the staleness is larger than a few versions. For this reason we attempt to keep staleness as low as possible in our experiments.

M.3 Sample Quality — Sampling and Sample Reuse

We found that increasing sample reuse causes a significant decrease in performance. As long as the optimizers are reusing data, adding additional rollout workers appears to be a relatively cheap way to accelerate training. CPUs are often easier and cheaper to scale up than GPUs and this can be a significant performance boost in some setups.

The fact that our algorithms benefit from extremely low sample reuse underlines how sample inefficient they are. Ideally, our training methods could take a small amount of experience and use that to learn a great deal, but currently we cannot even usefully optimize over that experience for more than a couple of gradient steps. Learning to use rollout data more efficiently is one of the major areas for future work in RL research.

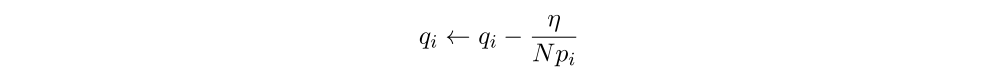

N Self-play

OpenAI Five is trained without any human gameplay data through a self-improvement process named self-play. This technique was successfully used in prior work to obtain super human performance in a variety of multiplayer games. In self-play training, we continually pit the current best version of an agent against itself or older versions, and optimize for new strategies that can defeat these past and present opponents.

In training OpenAI Five 80% of the games are played against the latest set of parameters, and 20% play against past versions. We play occasionally against past parameter versions in order to obtain more robust strategies and avoid strategy collapse in which the agent forgets how to play against a wide variety of opponents because it only requires a narrow set of strategies to defeat its immediate past version.

OpenAI Five uses a dynamic sampling system in which each past opponent i = 1..N is given a quality score qi. Opponent agents are sampled according to a softmax distribution; agent i is chosen with probability pi proportional to e^qi. Every 10 iterations we add the current agent to past opponent pool and initialize its quality score to the maximum of the existing qualities. After each rollout game is completed, if the past opponent defeats the current agent, no update is applied. If the current agent defeats a past opponent, an update is applied proportional to a learning rate constant η (which we fix at 0.01):

We see the opponent distribution at several points in early training. The spread of the distribution gives a good picture of how quickly the agent is improving: when the agent is improving rapidly, then older opponents are worthless to play against and have very low scores; when progress is slower the agent plays against a wide variety of past opponents.

O Exploration

Exploration is a well-known and well-researched problem in the context of RL. We encourage exploration in two different ways: by shaping the loss (entropy and team spirit) and by randomizing the training environment.

O.1 Loss function

We use entropy bonus to encourage exploration. This bonus is added to the PPO loss function in the form of cSπθ, where c is a hyperparameter referred to as entropy coefficient. In initial stages of training a long-running experiment like OpenAI Five or Rerun we set it to an initial value and lower it during training. We find that using entropy bonus prevents premature convergence to suboptimal policy. We see that entropy bonus of 0.01 (our default) performs best. We also find that setting it to 0 in early training, while not optimal, does not completely prevent learning. We introduced a hyperparameter team spirit to control whether agents optimize for their individual reward or the shared reward of the team. From the early training and speedup curves for team spirit, we see evidence that early in training, lower team spirits do better. At the very start team spirit 0 is the best, quickly overtaken by team spirit 0.3 and 0.5. We hypothesize that later in training team spirit 1.0 will be best, as it is optimizing the actual reward signal of interest.

O.2 Environment Randomization

We further encouraged exploration through randomization of the environment, with three simultaneous goals:

-

If a long and very specific series of actions is necessary to be taken by the agent in order to randomly stumble on a reward, and any deviation from that sequence will result in negative advantage, then the longer this series, the less likely is agent to explore this skill thoroughly and learn to use it when necessary.

-

If an environment is highly repetitive(重复的), then the agent is more likely to find and stay in a local minimum.

-

In order to be robust to various strategies humans employ, our agents must have encountered a wide variety of situations in training. This parallels the success of domain randomization in transferring policies from simulation to real-world robotics.

We randomize many parts of the environment:

-

Initial State(初始属性)

-

Lane Assignments(兵线分配)

-

Roshan Health(肉山血量)

-

Hero Lineup(英雄阵容)

-

Item Selection(物品选择)