Paper 43: Dueling Network Architectures for Deep Reinforcement Learning (Dueling DQN)

Abstract

-

Our dueling network represents two separate estimators: one for the state value function and one for the state-dependent action advantage function.

-

The main benefit of this factoring is to generalize learning across actions without imposing any change to the underlying reinforcement learning algorithm.

1 Introduction

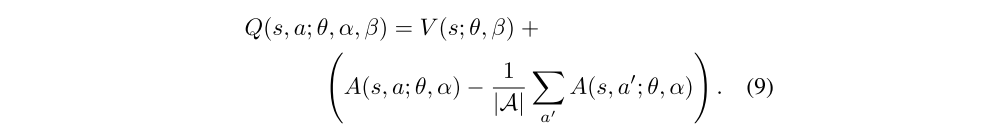

We take an alternative but complementary approach of focusing primarily on innovating a neural network architecture that is better suited for model-free RL. This approach has the benefit that the new network can be easily combined with existing and future algorithms for RL. That is, this paper advances a new network (Figure 1), but uses already published algorithms.

Figure 1: A popular single stream Q-network (top) and the dueling Q-network (bottom).

The proposed network architecture, which we name the dueling architecture, explicitly separates the representation of state values and (state-dependent) action advantages. The dueling architecture consists of two streams that represent the value and advantage functions, while sharing a common convolutional feature learning module. The two streams are combined via a special aggregating layer to produce an estimate of the state-action value function Q as shown in Figure 1. This dueling network should be understood as a single Q network with two streams that replaces the popular single-stream Q network in existing algorithms such as DQN2015. The dueling network automatically produces separate estimates of the state value function and advantage function, without any extra supervision.

Intuitively, the dueling architecture can learn which states are (or are not) valuable, without having to learn the effect of each action for each state. This is particularly useful in states where its actions do not affect the environment in any relevant way.

In the experiments, we demonstrate that the dueling architecture can more quickly identify the correct action during policy evaluation as redundant or similar actions are added to the learning problem.

1.1. Related Work

The dueling architecture represents both the value V(s) and advantage A(s, a) functions with a single deep model whose output combines the two to produce a state-action value Q(s, a). Unlike in advantage updating, the representation and algorithm are decoupled by construction. Consequently, the dueling architecture can be used in combination with a myriad of model free RL algorithms.

2 Background

2.1 Deep Q-networks

2.2 Double Deep Q-networks

2.3 Prioritized Replay

3 The Dueling Network Architecture

The key insight behind our new architecture is that for many states, it is unnecessary to estimate the value of each action choice. For example, in the Enduro game setting, knowing whether to move left or right only matters when a collision is eminent. In some states, it is of paramount importance to know which action to take, but in many other states the choice of action has no repercussion on what happens. For bootstrapping based algorithms, however, the estimation of state values is of great importance for every state.

To bring this insight to fruition, we design a single Q-network architecture, as illustrated in Figure 1, which we refer to as the dueling network. The lower layers of the dueling network are convolutional as in the original DQN2015. However, instead of following the convolutional layers with a single sequence of fully connected layers, we instead use two sequences (or streams) of fully connected layers. The streams are constructed such that they have the capability of providing separate estimates of the value and advantage functions. Finally, the two streams are combined to produce a single output Q functions.

Since the output of the dueling network is a Q function, it can be trained with the many existing algorithms, such as DDQN and SARSA. In addition, it can take advantage of any improvements to these algorithms, including better replay memories, better exploration policies, intrinsic motivation, and so on.

The module that combines the two streams of fully-connected layers to output a Q estimate requires very thoughtful design.

Let us consider the dueling network shown in Figure 1, where we make one stream of fully-connected layers output a scalar V(s; θ, β), and the other stream output an |A|-dimensional vector A(s, a; θ, α). Here, θ denotes the parameters of the convolutional layers, while α and β are the parameters of the two streams of fully-connected layers.

Using the definition of advantage, we might be tempted to construct the aggregating module as follows:

Note that this expression applies to all (s, a) instances; that is, to express this equation in matrix form we need to replicate the scalar, V(s; θ, β), |A| times.

However, we need to keep in mind that Q(s, a; θ, α, β) is only a parameterized estimate of the true Q-function. Moreover, it would be wrong to conclude that V(s; θ, β) is a good estimator of the state-value function, or likewise that A(s, a; θ, α) provides a reasonable estimate of the advantage function.

The equation is unidentifiable in the sense that given Q we cannot recover V and A uniquely. To see this, add a constant to V(s; θ, β) and subtract the same constant from A(s, a; θ, α). This constant cancels out resulting in the same Q value. This lack of identifiability is mirrored by poor practical performance when this equation is used directly.

To address this issue of identifiability, we can force the advantage function estimator to have zero advantage at the chosen action. That is, we let the last module of the network implement the forward mapping

Now, for

we obtain Q(s, a∗; θ, α, β) = V(s; θ, β). Hence, the stream V(s; θ, β) provides an estimate of the value function, while the other stream produces an estimate of the advantage function.

An alternative module replaces the max operator with an average: