Paper 51: Learning to Walk in the Real World with Minimal Human Effort

本文将 SAC 算法应用于实际的足式机器人案例中。

Abstract

-

Reliable and stable locomotion has been one of the most fundamental challenges for legged robots. DRL has emerged as a promising method for developing such control policies autonomously. In this paper, we develop a system for learning legged locomotion policies with DRL in the real world with minimal human effort.

-

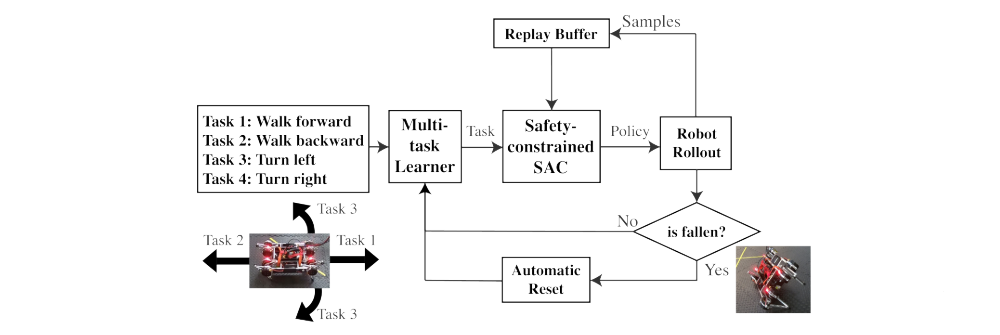

The key difficulties for on-robot learning systems are automatic data collection and safety. We overcome these two challenges by developing a multi-task learning procedure, an automatic reset controller, and a safety-constrained RL framework.

-

We tested our system on the task of learning to walk on three different terrains: flat ground, a soft mattress, and a doormat with crevices. Our system can automatically and efficiently learn locomotion skills on a Minitaur robot with little human intervention.

1 Introduction

Reliable and stable locomotion has been one of the most fundamental challenges in the field of robotics. Traditional hand-engineered controllers often require expertise and manual effort to design. While this can be effective for a small range of environments, it is hard to scale to the large variety of situations that the robot may encounter in the real world. In contrast, DRL can learn control policies automatically, without any prior knowledge about the robot or the environment. In principle, each time the robot walks on a new terrain, the same learning process can be applied to acquire an optimal controller for that environment.

However, despite the recent successes of DRL, these algorithms are often exclusively evaluated in simulation. Building fast and accurate simulations to model the robot and the rich environments that the robot may be operating in is extremely difficult. For this reason, we aim to develop a DRL system that can learn to walk autonomously in the real world. There are many challenges to design such a system. In addition to finding a stable and efficient DRL algorithm, we need to address the challenges associated with the safety and the automation of the learning process. During training, the robot may fall and damage itself, or leave the training area, which will require labor-intensive human intervention. Because of this, prior work that studied learning locomotion in the real world has focused on statically stable robots or relied on tedious manual resets between roll-outs.

Minimizing human interventions is the key to a scalable RL system. In this paper, we focus on solving two bottlenecks in this problem: automation and safety. During training, the robot needs to automatically and safely retry the locomotion task hundreds or thousands of times. This requires the robot staying within the workspace bounds, minimizing the number of dangerous falls, and automating the resets between episodes. We accomplish all these via a multi-task learning procedure, a safety-constrained learner, and several carefully designed hardware/software components. By simultaneously learning to walk in different directions, the robot stays within the workspace. By automatically adjusting the balance between reward and safety, the robot falls dramatically less. By building hardware infrastructure and designing stand-up controllers, the robot automatically resets its states and enables continuous data collection.

Our main contribution is an autonomous real-world RL system for robotic locomotion, which allows a quadrupedal robot to learn multiple locomotion skills on a variety of surfaces, with minimal human intervention. We test our system to learn locomotion skills on flat ground, a soft mattress and a doormat with crevices. Our system can learn to walk on these terrains in just a few hours, with minimal human effort, and acquire distinct and specialized gaits for each one. In contrast to the prior work, in which approximately a hundred manual resets are required in the simple case of walking on the flat ground, our system requires zero manual resets in this case. We also show that our system can train four policies simultaneously (walking forward, backward and turning left and right), which form a complete skill-set for navigation and can be composed into an interactive directional walking controller at test time.

2 Related Work

We aim to develop an end-to-end on-robot training system that automatically learns locomotion skills from real-world experience, which requires no prior knowledge about the dynamics of the robot.

Deep RL also has been used to learn locomotion control policies, mostly in simulated environments. Despite its effectiveness, one of the biggest challenges is to transfer the trained policies to the real world, which often incurs significant performance degradation due to the discrepancy(差异)between the simulated and real environments. Although researchers have developed principled approaches for mitigating the sim-to-real issue, including system identification, domain randomization, and meta-learning, it remains an open problem.

Researchers have investigated applying RL to real robotic systems directly, which is intrinsically free from the sim-to-real gap. The approach of learning on real robots has achieved SOTA performance on manipulation and grasping tasks, by collecting a large amount of interaction data on real robots. However, applying the same method to underactuated legged robots is challenging.

-

One major challenge is the need to

reset the robot to the proper initial states after each episode of data collection, for hundreds or even thousands of roll-outs. Researchers tackle this issue by developing external resetting devices for lightweight robots, such as a simple 1-DoF system or an articulated robotic arm. Otherwise, the learning process requires a large number of manual resets between roll-outs, which limits the scalability of the learning system. -

Another challenge is to

guarantee the safety of the robot during the entire learning process. Safety in RL can be formulated as aconstrained Markov Decision Process (cMDP), which is often solved by the Lagrangian relaxation procedure. Theoretical foundation of cMDP problems guarantees to improve both rewards and safety constraints. Many researchers have proposed extensions of the existing DRL algorithms to address safety, such as learning an additional safety layer that projects raw actions to a safe feasibility set, learning the boundary of the safe states with a classifier, expanding the identified safe region progressively, or training a reset policy alongside with a task policy.

In this paper, we focus on developing an autonomous and safe learning system for legged robots, which can learn locomotion policies with minimal human intervention. Closest to our work is the prior paper which also uses soft actor-critic (SAC) to train walking policies in the real world. In contrast to this work, our focus is on eliminating the need for human intervention, while the prior method requires a person to intervene(干涉)hundreds of times during training. We further demonstrate that we can learn locomotion on challenging terrains, and simultaneously learn multiple policies, which can be composed into an interactive directional walking controller at test time.

3 Overview

Our goal is to develop an automated system for learning locomotion gaits in the real world with minimal human intervention. Aside from incorporating a stable and efficient DRL algorithm, our system needs to address the following challenges.

-

First, the robot must

remain within the training area (workspace), which is difficult if the system only learns a single policy that walks in one direction. We utilize amulti-task learning framework, which simultaneously learns multiple locomotion tasks for walking in different directions, such as walking forward, backward, turning left or right. This multi-task learner selects the task to learn according to the relative position of the robot in the workspace. For example, if the robot is about the leave the workspace, the selected task-to-learn would be walking backward. Using this simplestate machine scheduler, the robot can remain within the workspace during the entire training process. -

Second, the system needs to

minimize the number of fallsbecause falling can result in substantially longer training times due to the overhead of experiment reset after each fall. Even worse, the robot can get damaged after repeated falls. Weaugment the Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) formulation with a safety constraintthat limits the roll and the pitch of the robot’s torso(躯干). Solving this cMDP greatly reduces the number of falls during training. -

Third, in cases where falling is inevitable, the robot needs to

stand up and reset its pose. We designed a stand-up controller, which allows the robot to stand up in a wide variety of fallen configurations.

Our system, combining all these components, effectively reduces the number of human interventions to zero in most of the training runs.

Overview of our learning system is as above. We solve three main automation challenges, leaving the workspace, falling, and resetting, by multi-task learning, a safety-constrained SAC algorithm, and an automatic reset controller.

5 Automated Learning in the Real World

-

Multi-Task Learning

An important cause of human intervention is the need to move the robot back to the initial position after each episode. Otherwise, the robot would quickly leave the limit-sized workspace within a few rollouts. Carrying a heavy-legged robot back-and-forth hundreds of times is labor-intensive. We develop a multi-task learning method with a simple state machine scheduler that generates an interleaved schedule of multi-directional locomotion tasks, in which the robot will learn to walk towards the center of the workspace automatically.

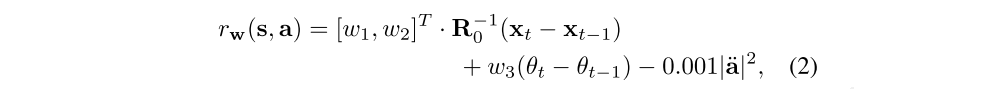

In our formulation, a task is defined by the desired direction of walking with respect to its initial position and orientation at the beginning of each roll-out. More specifically, the task reward r is parameterized by a three dimensional task vector w = [w1, w2, w3]T:

where R0 is the rotation matrix of the base at the beginning of the episode, xt and θt are the position and yaw angle of the base in the horizontal plane at time t, and a¨ measures smoothness of actions, which is the desired motor acceleration in our case. This task vector w defines the desired direction of walking. For example, walking forward is [1, 0, 0]T and tursning left is [0, 0, 0.5]T. Note that the tasks are locally defined and invariant to the selection of the starting position and orientation of each episode.

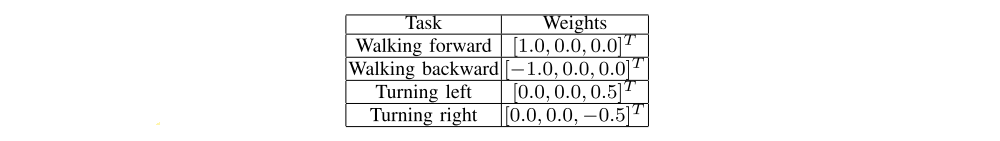

At the beginning of the episode, the scheduler determines the next task to learn from the set of predefined tasks W = {w1, · · · ,wn} based on the relative position of the center of the workspace in the robot’s coordinate. Refer to the following table for the complete set of tasks.

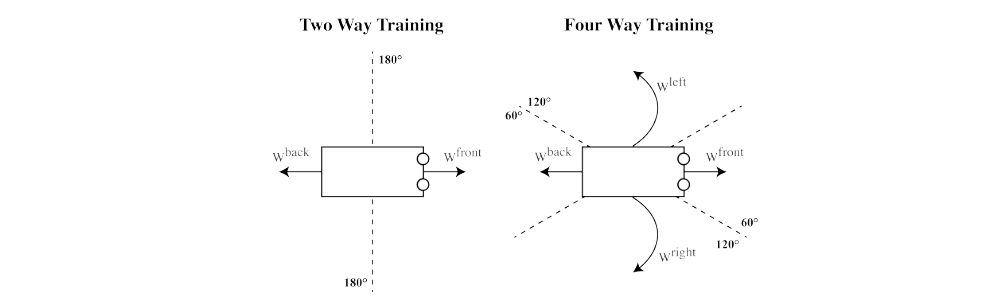

In effect, our scheduler selects the task in which the desired walking direction is pointing towards the center. This is done by dividing the workspace in the robot’s coordinate with the fixed angles and selecting the task where the center is located in its corresponding subdivision. Assuming we have two tasks: forward and backward walking, the scheduler will select the forward task if the workspace center is in front of the robot, and select the backward task in the other case. Note that a simple round-robin scheduler will not work because the tasks may not be learned at the same rate.

Our multi-task learning method is based on two assumptions:

-

First, we assume that even a partially trained policy still can move the robot in the desired direction even by a small amount most of the time. In practice, we find this to be true, since the initial policy is not likely to move the robot far away from the center, and

as the policy improves, the robot quickly begins to move in the desired direction, even if it does so slowly and unreliably at first. Usually after 10 to 20 roll-outs, the robot starts to move at least 1 cm, by pushing its base in the desired direction. -

The second assumption is that,

for each task in the set W, there is a counter-task that moves in the opposite direction. For example, walking forward versus backward or turning left versus right. Therefore, if one policy drives the robot to the boundary of the workspace, its counter-policy can bring it back.

In our experience, both assumptions hold for most scenarios, unless the robot accidentally gets stuck at the corners of the workspace.

We train a policy for each task with a separate instance of learning, without sharing actors, critics, or replay buffer. We made this design decision because we did not achieve clear performance gain when we experimented with weights and data sharing, probably because the definition of tasks is discrete and the experience from one task may not be helpful for other tasks.

Although multi-task learning reduces the number of out-of-bound failures by scheduling proper task-to-learn between episodes, the robot can still occasionally leave the workspace if it travels a long distance in one episode. We prevent this failure by triggering early termination (ET) when the robot is near and continues moving towards the boundary. In contrast to falling, this early termination requires special treatments for return calculation. Since the robot does not fall and can continue executing the task if it is not near the boundary, we take future rewards into consideration when we compute the target values of Q functions.

-

RL with Safety Constraints

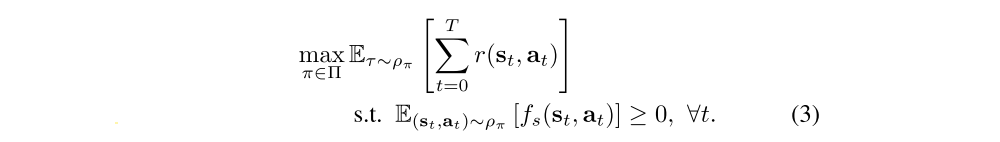

Repeated falls may not only damage the robot, but also significantly slow down training, since the robot must stand up after it falls. To mitigate this issue, we formulate a constrained MDP to find the optimal policy that maximizes the sum of rewards while satisfying the given safety constraints fs:

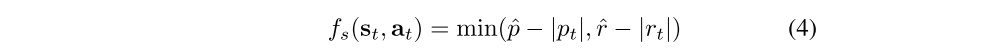

In our implementation, we design the safety constraints to prevent forward or backward falls that can easily damage the servo motors:

where p and r are the pitch and roll angles of the robot’s torso, and pˆ and rˆ are the maximum allowable tilt(倾斜), where they are set to π/12 and π/6 for all experiments.

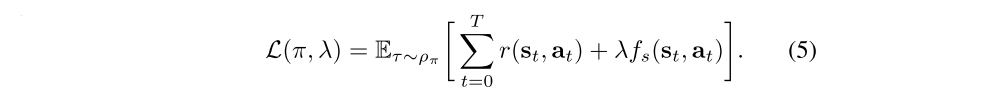

We can rewrite the constrained optimization by introducing a Lagrangian multiplier λ:

We optimize this objective using the dual gradient decent method, which alternates between the optimization of the policy π and the Lagrangian multiplier λ.

-

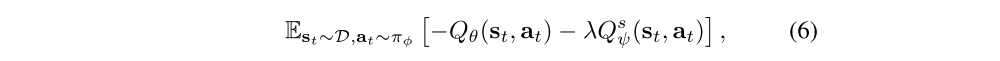

First, we train both Q functions for the regular reward Qθ and the safety term Qsψ, which are parameterized by θ and ψ respectively, using the formulation similar to prior work.

-

Then we can obtain the following

actor loss: where D is the replay buffer.

-

Finally, we can learn the Lagrangian multiplier λ by minimizing the loss J(λ):

-

Additional System Designs for Autonomous Training

We developed additional hardware and software features to facilitate a safe and autonomous real-world training environment.

-

First, while safety constraints significantly reduce the number of falls, experiencing some falls is inevitable because most RL algorithms rely on failure experience to learn effective control policies. To eliminate the manual resets after the robot falls, we

develop an automated stand-up controllerthat can recover the robot from a wide range of failure configurations. Our stand-up controller ismanually-engineered based on a simple state machine, which pushes the leg on the fallen side or adjusts the leg angles to roll back to the initial orientation. One challenge of designing such a stand-up controller is that the robot may not have enough space and torque to move its legs underneath its body in certain falling configurations due to the weak direct-drive motors. For this reason, we attach a safety box that is made of cardboard underneath the robot. When the robot falls, this small box gives the robot additional space for moving its legs, which prevents the legs from getting stuck and the servos from overheating. -

Second, we find that the robot often gets tangled(缠住)by the tethering cables(系绳电缆)when it walks and turns. We

develop a cable management systemso that all the tethering cables, including power, communication, and motion capture, are hung above the robot. We wire the cables through a 1.2 m rod that is mounted at the height of 2.5 m and adjust the cables length to maintain the proper slackness. Since our workspace has an elongated shape (5.0m by 2.0m), we connect one end of the rod to a hinge joint at the midpoint of the long side of the workspace, which allows the other end of the rod to follow the robot passively. -

Third, to reduce the wear-and-tear(磨损)of the motors due to the jerky(不平稳的)random exploration of the RL algorithm, we

post-process the action commandswith a first-order low-pass Butterworth filter with a cutoff frequency of 5 Hz.