Paper 53: Large-Scale Study of Curiosity-Driven Learning

这篇文章不使用外在的奖励, 仅使用 curiosity 这种内在奖励,就能够在诸多 Atari 游戏上有很好的表现, 甚至在超级马里奥上能顺利通过11关, ICM 可以认为是本篇工作的后续。

Zhihu Blog

Abstract

RL algorithms rely on carefully engineering environment rewards that are extrinsic to the agent. However, annotating each environment with hand-designed, dense rewards is not scalable, motivating the need for developing reward functions that are intrinsic to the agent. Curiosity is a type of intrinsic reward function which uses prediction error as reward signal. In this paper:

-

We perform the first large-scale study of purely curiosity-driven learning, i.e. without any extrinsic rewards, across 54 standard benchmark environments, including the Atari game suite. Our results show surprisingly good performance, and a high degree of alignment between the intrinsic curiosity objective and the hand-designed extrinsic rewards of many game environments.

-

We investigate the effect of using different feature spaces for computing prediction error and show that random features are sufficient for many popular RL game benchmarks, but learned features appear to generalize better (e.g. to novel game levels in Super Mario Bros.).

-

We demonstrate limitations of the prediction-based rewards in stochastic setups.

1 Introduction

Most of the success in RL has been achieved when reward function is dense and well-shaped, e.g., a running “score” in a video game. However, designing a well-shaped reward function is a notoriously challenging engineering problem. An alternative to “shaping” an extrinsic reward is to supplement it with dense intrinsic rewards, that is, rewards that are generated by the agent itself. Examples of intrinsic reward include “curiosity” which uses prediction error as reward signal, and “visitation counts” which discourages the agent from revisiting the same states. The idea is that these intrinsic rewards will bridge the gaps between sparse extrinsic rewards by guiding the agent to efficiently explore the environment to find the next extrinsic reward.

But what about scenarios with no extrinsic reward at all? This is not as strange as it sounds. Developmental psychologists talk about intrinsic motivation (i.e., curiosity) as the primary driver in the early stages of development: babies appear to employ goal-less exploration to learn skills that will be useful later on in life. There are plenty of other examples, from playing Minecraft to visiting your local zoo, where no extrinsic rewards are required. Indeed, there is evidence that pre-training an agent on a given environment using only intrinsic rewards allows it to learn much faster when fine-tuned to a novel task in a novel environment. Yet, so far, there has been no systematic study of learning with only intrinsic rewards.

In this paper, we perform a large-scale empirical study of agents driven purely by intrinsic rewards across a range of diverse simulated environments. In particular, we choose the dynamics-based curiosity model of intrinsic reward presented in prior work because it is scalable and trivially parallelizable, making it ideal for large-scale experimentation. The central idea is to represent intrinsic reward as the error in predicting the consequence of the agent’s action given its current state, i.e., the prediction error of learned forward-dynamics of the agent. We thoroughly investigate the dynamics-based curiosity across 54 environments: video games, physics engine simulations, and virtual 3D navigation tasks.

To develop a better understanding of curiosity-driven learning, we further study the crucial factors that determine its performance. In particular, predicting future state in high dimensional raw observation space (e.g., images) is a challenging problem and, as shown by recent works, learning dynamics in an auxiliary feature space leads to improved results. However, how one should choose such an embedding space is a critical, yet open research problem. Through a systematic ablation, we ` examine the role of different ways to encode agent’s observation such that an agent can perform well driven purely by its own curiosity. To ensure stable online training of dynamics, we argue that the desired embedding space should: (*a*) be compact(紧凑的)in terms of dimensionality, (*b*) preserve sufficient information about the observation, and (*c*) be a stationary function of the observations. We show that encoding observations via a random network turn out to be a simple, yet effective technique for modeling curiosity across many popular RL benchmarks`. This might suggest that many popular RL video game test-beds are not as visually sophisticated as commonly thought. Interestingly, we discover that although random features are sufficient for good performance at training, the learned features appear to generalize better (e.g., to novel game levels in Super Mario Bros.).

In summary:

-

We perform a large-scale study of curiosity-driven exploration across a variety of environments including: the set of Atari games, Super Mario Bros., virtual 3D navigation in Unity, multi-player Pong, and Roboschool environments.

-

We extensively investigate different feature spaces for learning the dynamics-based curiosity: random features, pixels, inverse-dynamics and variational auto-encoders and evaluate generalization to unseen environments.

-

We conclude by discussing some limitations of a direct prediction-error based curiosity formulation. We observe that if the agent itself is the source of stochasticity in the environment, it can reward itself without making any actual progress. We empirically demonstrate this limitation in a 3D navigation task where the agent controls different parts of the environment.

2 Dynamics-based Curiosity-driven Learning

We want to incentivize this agent with a reward rt relating to how informative the transition was. To provide this reward, we use an exploration bonus involving the following elements: (a) a network to embed observations into representations φ(x), (b) a forward dynamics network to predict the representation of the next state conditioned on the previous observation and action p(φ(xt+1)|xt, at). Given a transition tuple {xt, xt+1, at}, the exploration reward (also called the surprisal) is then defined as

An agent trained to maximize this reward will favor transitions with high prediction error, which will be higher in areas where the agent has spent less time, or in areas with complex dynamics. Such a dynamics-based curiosity has been shown to perform quite well across scenarios especially when the dynamics are learned in an embedding space rather than raw observations. In this paper, we explore dynamics-based curiosity and use MSE corresponding to a fixed-variance Gaussian density as surprisal, i.e.,

where f is the learned dynamics model. However, any other density model could be used.

2.1 Feature spaces for forward dynamics

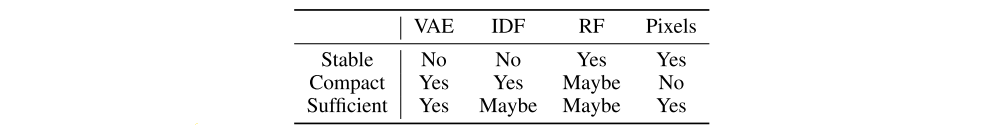

Consider the representation φ in the curiosity formulation above. If φ(x) = x, the forward dynamics model makes predictions in the observation space. A good choice of feature space can make the prediction task more tractable and filter out irrelevant aspects of the observation space. But, what makes a good feature space for dynamics driven curiosity? We narrow down a few qualities that a good feature space should have:

-

Compact: The features should be easy to model by being low(er)-dimensional and filtering out irrelevant parts of the observation space.

-

Sufficient: The features should contain all the important information. Otherwise, the agent may fail to be rewarded for exploring some relevant aspect of the environment.

-

Stable: Non-stationary rewards make it difficult for reinforcement agents to learn. Exploration bonuses by necessity introduce non-stationarity since what is new and novel becomes old and boring with time. In a dynamics-based curiosity formulation, there are two sources of non-stationarity: the forward dynamics model is evolving over time as it is trained and the features are changing as they learn. The former is intrinsic to the method, and the latter should be minimized where possible.

In this work, we systematically investigate the efficacy of a number of feature learning methods, summarized briefly as follows:

-

Pixels: The simplest case is where φ(x) = x and we fit our forward dynamics model in the observation space. Pixels are sufficient, since no information has been thrown away, and stable since there is no feature learning component. However, learning from pixels is tricky because the observation space may be high-dimensional and complex.

-

Random Features (RF): The next simplest case is where we take our embedding network, a convolutional network, and fix it after random initialization. Because the network is fixed, the features are stable. The features can be made compact in dimensionality, but they are not constrained to be. However, random features may fail to be sufficient.

-

Variational Autoencoders (VAE): VAEs were introduced to fit latent variable generative models p(x, z) for observed data x and latent variable z with prior p(z) using variational inference. The method calls for an inference network q(z|x) that approximates the posterior p(z|x). This is a feedforward network that takes an observation as input and outputs a mean and variance vector describing a Gaussian distribution with diagonal covariance. We can then use the mapping to the mean as our embedding network φ. These features will be a low-dimensional approximately sufficient summary of the observation, but they may still contain some irrelevant details such as noise, and the features will change over time as the VAE trains.

-

Inverse Dynamics Features (IDF): Given a transition (st, st+1, at) the inverse dynamics task is to predict the action at given the previous and next states st and st+1. Features are learned using a common neural network φ to first embed st and st+1. The intuition is that the features learned should correspond to aspects of the environment that are under the agent’s immediate control. This feature learning method is easy to implement and in principle should be invariant to certain kinds of noise. A potential downside could be that the features learned may not be sufficient, that is they do not represent important aspects of the environment that the agent cannot immediately affect.

Table summarizing the categorization of different kinds of feature spaces considered.

Note that the learned features are not stable because their distribution changes as learning progresses. One way to achieve stability could be to pre-train VAE or IDF networks. However, unless one has access to the internal state of the game, it is not possible to get a representative data of the game scenes to train the features. One way is to act randomly to collect data, but then it will be biased to where the agent started, and won’t generalize further. Since all the features involve some trade-off of desirable properties, it becomes an empirical question as to how effective each of them is across environments.

2.2 Practical considerations in training an agent driven purely by curiosity

Deciding upon a feature space is only first part of the puzzle in implementing a practical system. Here, we detail the critical choices we made in the learning algorithm. Our goal was to reduce non-stationarity in order to make learning more stable and consistent across environments. Through the following considerations outlined below, we are able to get exploration to work reliably for different feature learning methods and environments with minimal changes to the hyper-parameters.

-

PPO. In general, we have found PPO algorithm to be a robust learning algorithm that requires little hyper-parameter tuning, and hence, we stick to it for our experiments.

-

Reward normalization. Since the reward function is non-stationary, it is useful to normalize the scale of the rewards so that the value function can learn quickly. We did this by dividing the rewards by a running estimate of the standard deviation of the sum of discounted rewards.

-

Advantage normalization. While training with PPO, we normalize the advantages in a batch to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.

-

Observation normalization. We run a random agent on our target environment for 10000 steps, then calculate the mean and standard deviation of the observation and use these to normalize the observations when training. This is useful to ensure that the features do not have very small variance at initialization and to have less variation across different environments.

-

More actors. The stability of the method is greatly increased by increasing the number of parallel actors (which affects the batch-size) used. We typically use 128 parallel runs of the same environment for data collection while training an agent.

-

Normalizing the features. In combining intrinsic and extrinsic rewards, we found it useful to ensure that the scale of the intrinsic reward was consistent across state space. We achieved this by using batch-normalization in the feature embedding network.

2.3 ‘Death is not the end’: discounted curiosity with infinite horizon

One important point is that the use of an end of episode signal, sometimes called a ‘done’, can often leak information about the true reward function. If we don’t remove the ‘done’ signal, many of the Atari games become too simple. For example, a simple strategy of giving +1 artificial reward at every time-step when the agent is alive and 0 on death is sufficient to obtain a high score in some games, for instance, the Atari game ‘Breakout’ where it will seek to maximize the episode length and hence its score. In the case of negative rewards, the agent will try to end the episode as quickly as possible.

In light of this, if we want to study the behavior of pure exploration agents, we should not bias the agent. In the infinite horizon setting (i.e., the discounted returns are not truncated at the end of the episode and always bootstrapped using the value function), death is just another transition to the agent, to be avoided only if it is boring. Therefore, we removed ‘done’ to separate the gains of an agent’s exploration from merely that of the death signal. In practice, we do find that the agent avoids dying in the games since that brings it back to the beginning of the game, an area it has already seen many times and where it can predict the dynamics well. This subtlety has been neglected by previous works showing experiments without extrinsic rewards.

5 Discussion

We have shown that our agents trained purely with a curiosity reward are able to learn useful behaviours in different environments. But this is not always true as there are some Atari games where exploring the environment does not correspond to extrinsic reward. More generally, these results suggest that, in environments designed by humans, the extrinsic reward is perhaps often aligned with the objective of seeking novelty. The game designers set up curriculums to guide users while playing the game explaining the reason Curiosity-like objective decently aligns with the extrinsic reward in many human-designed games.

-

Limitation of prediction error based curiosity

A more serious potential limitation is the handling of stochastic dynamics. If the transitions in the environment are random, then even with a perfect dynamics model, the expected reward will be the entropy of the transition, and the agent will seek out transitions with the highest entropy. Even if the environment is not truly random, unpredictability caused by a poor learning algorithm, an impoverished model class or partial observability can lead to exactly the same problem. We did not observe this effect in our experiments on games so we designed an environment to illustrate the point.

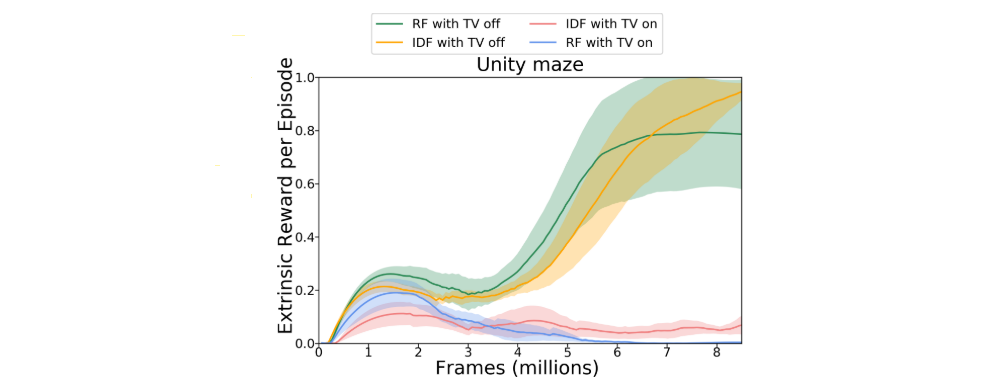

We return to the maze of Section 3.3 to empirically validate a common thought experiment called the noisy-TV problem. The idea is that local sources of entropy in an environment like a TV that randomly changes channels when an action is taken should prove to be an irresistible attraction to our agent. We take this thought experiment literally and add a TV to the maze along with an action to change the channel.

In the figure above we show how adding the noisy-TV affects the performance of IDF and RF. As expected the presence of the TV drastically slows down learning, but we note that if you run the experiment for long enough the agents do sometimes converge to getting the extrinsic reward consistently. We have shown empirically that stochasticity can be a problem, and so it is important for future work to address this issue in an efficient manner.

-

Future Work