Paper 55: AndroidEnv: A Reinforcement Learning Platform for Android

本文介绍的 AndroidEnv 是一个开放平台,适用于基于安卓生态的强化学习研究。通过一个统一的触屏接口,智能体能够与人们广泛使用的 App 应用服务进行交互。虽然智能体是在一个安卓服务模拟上进行训练的,但是可以部署到真实的服务中提升用户体验以及帮助进行设备测试和质量保证。

Github: https://github.com/deepmind/android_env.

1 Introduction

The agent-environment interaction in AndroidEnv matches that of a user and a real device: the screen pixels constitute the observations, the action space is defined by touchscreen gestures, the interaction is real-time, and actions are executed asynchronously, while the environment runs at its own time scale.

2 Environment Features

AndroidEnv implements the dm_env API on top of an emulated Android device.

2.1 Real-time execution

2.2 Action interface

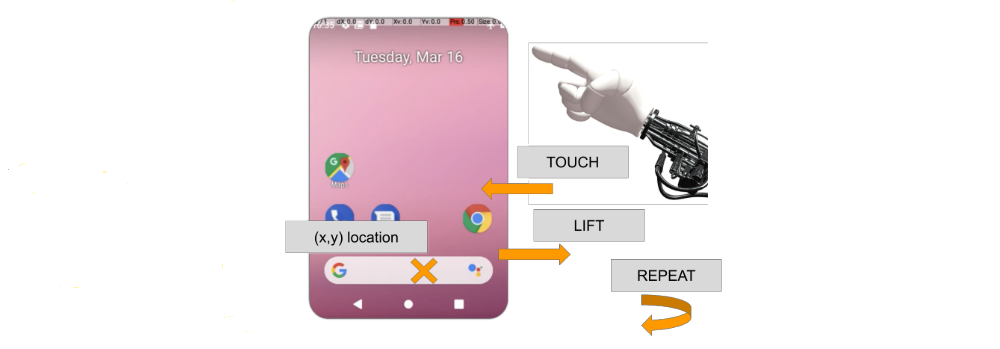

Figure 1 | The action space is composed of a discrete action type and a screen location.

-

Raw action space.

The native action space of the environment consists of a tuple consisting of a position (x, y) ∈ [0, 1] × [0, 1], determining the location of the action on the screen, and a discrete value ActionType ∈ {TOUCH, LIFT, REPEAT} indicating whether the agent opts for touching the screen at the indicated location, lifting the pointer from the screen, or repeating the last chosen action, respectively. This action space is the same across all tasks and apps.

It is worth noting that while two actions a1 = {ActionType = LIFT, position = (x1, y1)} and a2 = {ActionType = LIFT, position = (x2, y2)} are different from the agent’s perspective, in practice they result in the same effect on the device, because the lack of a touch has no association to a particular location.

-

Gestures.

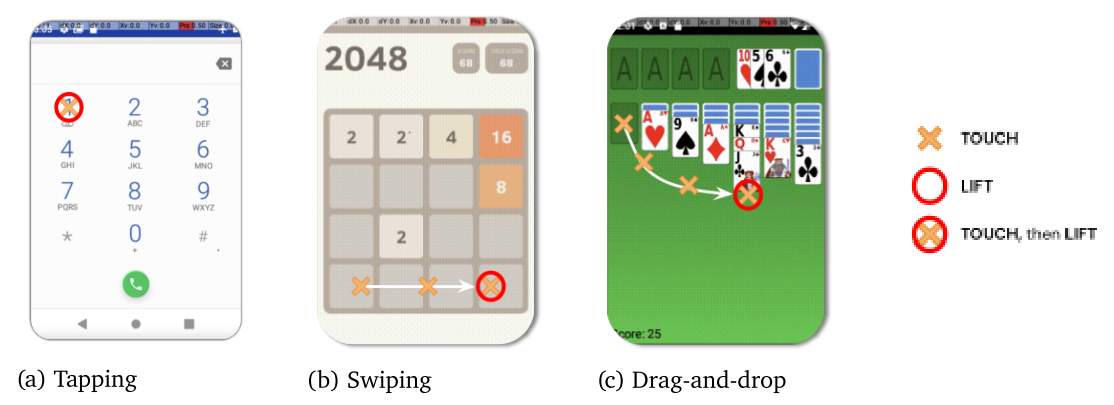

The complexity of the interface arises from the fact that individual raw actions on their own do not necessarily trigger a meaningful change in the environment. It is more useful for agents to control Android applications via gestures, such as pressing, long pressing, swiping, scrolling, or drag-and-drop. Each of these correspond to a particular sequence of raw actions: for example, a screen touch at a particular location, followed by a lift of the the imaginary finger is a sequence that Android can interpret as a press of a button. Similarly, Android will interpret a sequence of aligned touches as scrolling.

Figure 2 | Examples of gestures. Actions are performed one after the other, tracing out a particular path.

This distinction between the raw action space and a particular app interface makes AndroidEnv a challenging domain. A random sequence of actions will typically have a small probability of producing a meaningful gesture in most Android apps. This need to compose actions, paired with the difficulty of solving the underlying task itself, leads to a difficult exploration problem. For example, in order to learn to play chess in AndroidEnv, an agent must not only find a winning strategy, it also has to learn to move pieces through drag-and-drop gestures.

-

Relation to observations.

Another notable feature of AndroidEnv is the spatial correlation between actions and observations. Often, an action can result in local changes in the pixels near the location of the action, or the position of certain items in the observation might hint at the next best location to take an action. In particular, the screen is often suggestive of the kind of gestures the application expects: smartphone users would often find it intuitive to tap where they see an item in the shape of a button, or to scroll where they see a drop-down menu.

-

Altering the action space.

AndroidEnv allows users to define wrappers around the raw action space of the environment. For example, one might discretise the action space by splitting up the screen into a grid, restrict the ActionType to TOUCH, or group action sequences like [LIFT, TOUCH, LIFT] into a single tap action. We provide some useful and natural wrappers. Note that these wrappers alter the set of actions available to the agent, but not the way in which AndroidEnv interprets raw actions.

2.3 Observations

-

Observation space.

The observation space of AndroidEnv consists of three main components: {pixels, timedelta, orientation}. The most notable component is pixels, representing the current frame as an RGB image array. Its dimensions will depend on the device used (real or virtual), but given that it will correspond to real device screen sizes, this array will typically be large (of course, users can scale down their dimensionality, e.g. with wrappers). The timedelta component captures the amount of time passed since AndroidEnv fetched the last observation. The orientation, even though it does not affect the layout of the RGB image in the observation, might carry relevant information for the agent. For example, if there is text on the screen, its orientation is useful for automatic processing.

As mentioned above, observations often carry spatial cues(提示)and are suggestive of meaningful gestures to perform in a given state. The fact that the observation space is the same across all tasks is what makes it useful for agents, and creates the opportunity to generalize across tasks.

-

Task extras.

In addition to default observations, some tasks might expose structured information after each step. An extra in AndroidEnv is any information that the environment sends to aid the understanding of the task. The information sent through this channel is typically very useful for learning, yet difficult to extract from raw pixels. For example, extras may include signals indicating events such as a button press or opening of a menu, text displayed on the screen in string format, or a simple numerical representations of the displayed state. Note that extras are a standard mechanism for communicating information used in Android apps.

We note that, unlike the observation and raw action space, which are the same across all AndroidEnv, task extras are specific to individual tasks, are entirely optional, and may not be available at all. Furthermore, task extras, even if provided, are not part of the default observation; rather AndroidEnv returns them upon explicit request.

Figure 3 | Information available to the agent.

3 Tasks

While Android is an operating system with no inherent rewards or episodes, AndroidEnv provides a simple mechanism for defining tasks on it. Tasks capture information such as episode termination conditions, rewards, or the apps with which the agent can interact. Together, these define a specific RL problem for the agent.

-

Task structure.

We capture aspects that make up a task definition in a Task protocol buffer message. These include information on:

-

How to initialise the environment: for example, installing particular applications on the device. -

When should an episode be reset: for example, upon receiving a particular message from the device or app, or upon reaching a certain time limit. -

Events triggered upon an episode reset: for example, launching a given app, clearing the cache, or pinning the screen to a single app (hence restricting the agent’s interaction to that app). -

How to determine the reward: for example, this might depend on different signals coming from Android, such as Android accessibility service or log messages implemented in applications.

With these protocol buffer messages, users can define a wide variety of tasks on Android. For example, a task could be to set an alarm in the Android standard Clock app, by opening this app upon launch, and rewarding the agent and ending an episode once an alarm has been set. We detail the full specification of the protocol buffer message structure in the code repository.

-

Available tasks.