Paper 56: Unity: A General Platform for Intelligent Agents

逼真复杂的模拟环境长久以来驱动着前沿的人工智能研究,而 Unity 作为一个功能强大的游戏引擎,能够使得开发出的学习环境具备丰富的视觉呈现、精确的物理特性、更高的任务复杂度以及更好的智能体可交互性,环境构建过程更加灵活。我们认为现代游戏引擎非常适合作为助力学习环境开发的通用平台,本文将会介绍 Unity 引擎以及开源的 Unity ML-Agents Toolkit。

1 Introduction

The contributions of this work are:

-

Novel taxonomy(分类)of existing platforms used for research which classifies platforms in terms of their potential for complexity along the dimensions of sensory, physical, task-logic and social.

-

A detailed analysis of the Unity game engine and the Unity ML-Agents Toolkit as an instance of a general platform, the highest level of the proposed taxonomy.

-

A survey of current research conducted using Unity and critical areas in which progress is hindered(妨碍)by the current platforms but can be facilitated(促进)by a general platform such as Unity.

2 Anatomy of Environments and Simulators

In this section, we detail some of the characteristics of environments and simulators we believe are needed to advance the state of the field in AI research. We use the term environment to refer to the space in which an artificial agent acts and simulator to refer to the platform which computes the environment.

2.1 Environment Properties

As algorithms are able to solve increasingly difficult tasks, the complexity of the environments themselves must increase in order to continue to provide meaningful challenges. The specific axes of environmental complexity we believe are essential are sensory, physical, task logic, and social. In this subsection, we outline the role each of these play in the SOTA in AI.

-

Sensory Complexity

While ImageNet was mainly used for static image recognition tasks, its key component of visual complexity is necessary for many real-world decision-making problems, such as self-driving cars, household robots, and unmanned autonomous vehicles. Additionally, advances in CV algorithms, specifically around CNNs, were the motivation for the pixel-to-control approach eventually found in the DQN.

-

Physical Complexity

Many of the applied tasks researchers are interested in solving with AI involve not only rich sensory information, but a rich control scheme in which agents can interact with their dynamic environments in complex ways. The need for complex interaction often comes with the need for environments which replicate the physical properties of the target domain, typically the real world. This realism is essential to problems where the goal is to transfer a policy learned within a simulator to the real world, as would be the case for most robotics applications.

-

Task Logic Complexity

The game of Go, for example, which has long served as a test-bed for AI research, contains neither complex visuals nor complex physical interactions. Rather, the complexity comes from the large search space of possibilities open to the agent at any given time, and the difficulty in evaluating the value of a given board configuration. Meaningful simulation platforms should enable designers to naturally create such problems for the learning agents within them. These complex tasks might display hierarchical structure, a hallmark(品质证明)of human intelligence, or vary from instance to instance, thus requiring meta-learning or generalization to solve. The tasks may also be presented in a sequential manner, where independent sampling from a fixed distribution is not possible. This is often the case for human task acquisition in the real world, and the ability to learn new tasks over time is seen as a key-component of continual learning, and ultimately systems capable of AGI.

-

Social Complexity

The development of social behavior among groups of agents is of particular interest to many researchers in the field of AI. There are also classes of complex behavior which can only be carried out at the population level, such as the coordination needed to build modern cities. Additionally, the ability for multiple species to interact with one another is a hallmark of the development of ecosystems in the world, and would be desirable to simulate as well. A simulation platform designed to allow the study of communication and social behavior should then provide a robust multi-agent framework which enables interaction between agents of both the same population as well as interaction between groups of agents drawn from separate distributions.

2.2 Simulation Properties

In addition to the properties above, there are practical constraints imposed(强加)by the simulator itself which must be taken into consideration when designing environments for experimentation. Specifically, simulated environments must be flexibly controlled by the researcher and must run in a fast and distributed manner in order to provide the iteration time required for experimental research.

-

Fast & Distributed Simulation

Depending on the sample efficiency of the method used, modern ML algorithms often require up to billions of samples in order to converge to an optimal solution. As such, the ability to collect that data as quickly as possible is paramount(最重要的). One of the most appealing properties of a simulation is the ability for it to be run at a speed often orders of magnitude greater than that of the physical world. In addition to this increase in speed, simulations can often be run in parallel, allowing for orders of magnitude greater data collection than real-time serial experience in the physical world. The faster such algorithms can be trained, the greater the speed of iteration and experimentation that can take place, leading to faster development of novel methods.

-

Flexible Control

A simulator must also allow the researcher or developer a flexible level of control over the configuration of the simulation itself, both during development and at runtime. While treating the simulation as a black-box has been sufficient for certain advances in recent years, in many cases it also inhibits(抑制)use of a number of advanced ML approaches in which more dynamic feedback between the training process and the agents is essential. Curriculum learning(课程学习), for example, entails(需要)initially providing a simplified version of a task to an agent, and slowly increasing the task complexity as the agent’s performance increases. This method was used to achieve near human-level performance in a recent VizDoom competition. Such approaches are predicated on the assumption that the user has the capacity to alter the simulation to create such curricula in the first place. Additionally, domain randomization(域随机化) involves introducing enough variability into the simulation so that the models learned within the simulation can generalize to the real world. This often works by ensuring that the data distribution of the real world is covered within all of the variations presented within the simulation. This variation is especially important if the agent depends on visual properties of the environment to perform its task. It is often the case that without domain randomization, models trained in simulation suffer from a “reality gap” and perform poorly. Concretely, performing domain randomization often involves dynamically manipulating(控制)textures, lighting, physics, and object placement within a scene.

3 A Survey of Existing Simulators

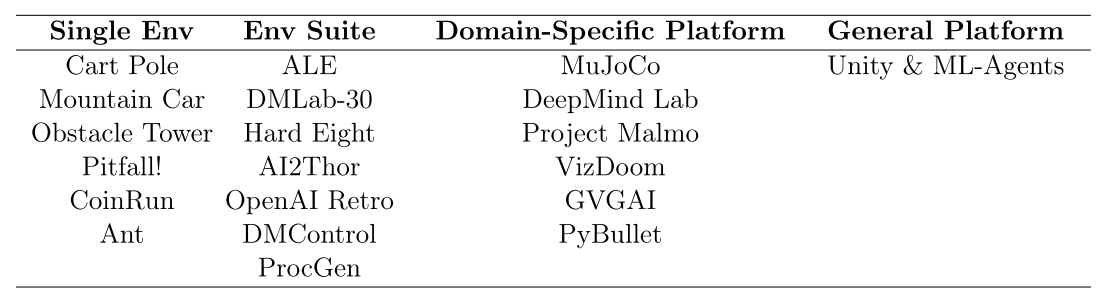

When surveying the landscape of simulators, environments, and platforms, we find that there exist four categories into which these items can be organized.

-

The first is Environment which consists of single, fixed environments that act as black-boxes from the perspective of the agent.

-

The second is Environment Suite. These consist of sets of environments packaged together and are typically used to benchmark the performance of an algorithm or method along some dimensions of interest. In most cases these environments all share the same or similar observation and action spaces, and require similar, but not necessarily identical skills to solve.

-

The third category is Domain-specific Platform. This describes platforms which allow the creation of sets of tasks within a specific domain such as locomotion or first-person navigation. These platforms are distinguished from the final category by their narrow focus in environments types. This can include limitations to the perspective the agent can take, the physical properties of the environment, or the nature of the interactions and tasks possible within the environment.

-

The fourth and final category is the General Platform whose members are

capable of creating environments with arbitrarily complex visuals, physical and social interactions, and tasks. The set of environments that can be created by platforms in this category is a super-set of those that can be created by or are contained within the other three categories. In principle, members of these categories can be used to define any AI research environment of potential interest. We find that modern video game engines represent a strong candidate for this category. In particular, we propose the Unity engine along with a toolkit for AI interactions such as ML-Agents as an example of this category. Note that other game engines such as the Unreal engine could serve as general platforms for AI research.The important missing element however is the set of useful abstractions and interfaces for conducting AI research, something present in all examples listed here, but not inherently part of any given game engine or programming language.

Table 1: Taxonomy of simulators based on flexibility of environment specification. Includes a subset of examples for illustrative purposes.

3.1 Common Simulators

-

Arcade Learning Environment

-

DeepMind Lab

-

Project Malmo

-

Physics Simulators

-

Vizdoom

4 The Unity Platform

Unity is a real-time 3D development platform that consists of a rendering and physics engine as well as a graphical user interface called the Unity Editor. Unity has received widespread adoption in the gaming, AEC (Architecture, Engineering, Construction), auto, and film industries and is used by a large community of game developers to make a variety of interactive simulations, ranging from small mobile and browser-based games to high-budget console games and AR/VR experiences.

Unity’s historical focus on developing a general-purpose engine to support a variety of platforms, developer experience levels, and game types makes the Unity engine an ideal candidate simulation platform for AI research. The flexibility of the underlying engine enables the creation of tasks ranging from simple 2D gridworld problems to complex 3D strategy games, physics-based puzzles, or multi-agent competitive games possible. Unlike many of the research platforms discussed above, the underlying engine is not restricted to any specific genre of gameplay or simulation, making Unity a general platform. Furthermore, the Unity Editor enables rapid prototyping and development of games and simulated environments.

A Unity Project consists of a collection of Assets. These typically correspond to files within the Project. Scenes are a special type of Asset which define the environment or level of a Project. Scenes contain a definition of a hierarchical composition of GameObjects, which correspond to the actual objects (either physical or purely logical) within the environment. The behavior and function of each GameObject is determined by the components attached to it. There are a variety of built-in components provided with the Unity Editor, including Cameras, Meshes, Renderers, RigidBodies, and many others. It is also possible to define custom components using C# scripts or external plugins.

4.1 Engine Properties

We demonstrate that Unity enables the complexity necessary along the key dimensions of environment properties for the creation of challenging learning environments.

-

Environment Properties

-

Sensory Cmplexity - The Unity engine enables

high-fidelity(保真度)graphical rendering. It supports pre-baked as well as real-time lighting and the ability to define custom shaders, either programmatically or via a visual scripting language. As such, it is possible to quickly render near-photorealistic(相片级)imagery to be used as training data for a ML model. It is also possible to render depth information, object masks, infrared(红外线), or images with noise injected into it through the use of custom shaders. Furthermore, the engine provides a means of defining audio signals which can serve as potential additional observational information to learning agents, as well as ray-cast based detection systems which can simulate Lidar. -

Physical Complexity - Physical phenomena in Unity environments can be simulated with either the Nvidia PhysX or Havok Physics engines. This enables

research in environments with simulated rigid body, soft body, particle, and fluid dynamics as well as ragdoll(布娃娃)physics. Furthermore, the extensible nature of the platform enables the use ofadditional 3rd party physics enginesif desired. For example, there are plugins available for Unity which provide both the Bullet and MuJoCo physics engines as alternatives to PhysX. -

Task Logic Complexity - The Unity Engine provides

a rich and flexible scripting system via C#. This system enables any form of gameplay or simulation to be defined and dynamically controlled. In addition to the scripting language,the GameObject and component system enables managing multiple instances of agents, policies, and environments, making it possible to define complex hierarchical tasks, or tasks which would require meta-learning to solve. -

Social Complexity -

The nature of the Unity scripting language and component system makes the posing of multi-agent scenarios simple and straightforward. Indeed, because the platform was designed to support the development of multi-player video games, a number of useful abstractions are already provided out of the box(开箱即用), such as theMultiplayer Networking system.

-

-

Simulation Properties

-

Fast & Distributed Simulation -

The physics and frame rendering of the Unity engine take place asynchronously. As such, it is possible to greatly increase the speed of the underlying simulation without the need to increase the frame rate of the rendering process.It is also possible to run Unity simulations without rendering if it is not critical to the simulation. In scenarios where rendering is desirable, such as learning from pixels, it is possible to control the frame rate and speed of game logic. Extensive control of the rendering quality also makes it possible to greatly increase the frame rate when desired. The added capabilities of the Unity engine do add additional overhead when attempting to simulate in a large-scale distributed fashion. The memory footprint(内存占用)of a Unity simulation is also larger than that of environments from other platforms such as an Atari game in the ALE. -

Flexible Control - It is possible to

control most aspects of the simulation programmatically, enabling researchers to define curricula, adversarial scenarios, or other complex methods of changing the learning environment during the training process. For example, GameObjects can be conditionally created and destroyed in real-time. In Section 5, we discuss ways in which further control of the simulation is made possible viaexposed simulation parameters and a Python API.

-

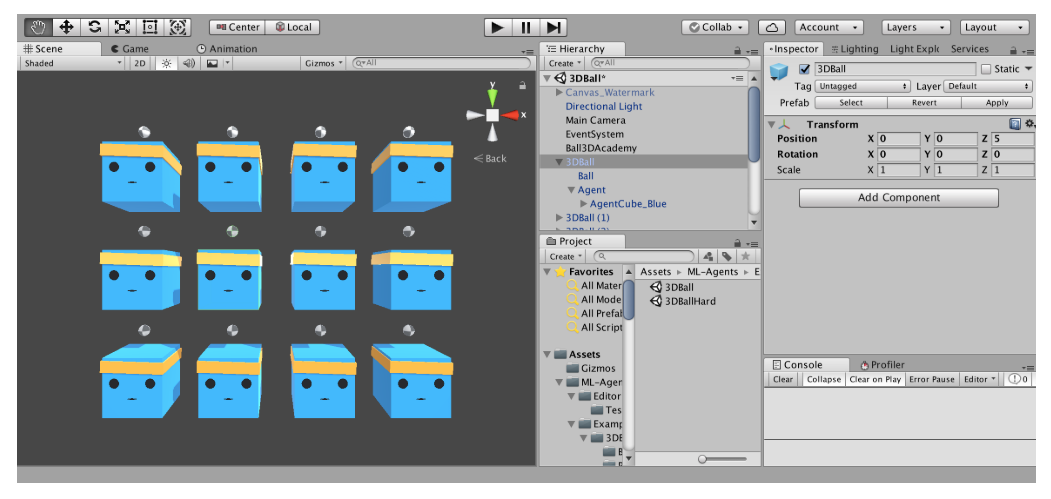

4.2 Unity Editor and Services

The Unity Editor is a graphical user interface used to create the content for 2D, 3D and AR / VR experiences. It is available on Windows, Mac and Linux.

Figure 1: The Unity Editor window on macOS.

The Unity Editor and its services provide additional benefits for AI research:

-

Create custom Scenes- Unity provides a large number of guides and tutorials on how to create Scenes within the Editor. This enables developers to quickly experiment with new environments of varying complexities, or novel tasks. Furthermore, an online asset store which contains tens of thousands of free and paid assets provides users access to a huge diversity of pre-built entities for their scene. -

Record local, expert demonstrations- The Unity Editor includes a Play mode which enables a developer to begin a simulation and control one or more of the agents in the Scene via a keyboard or game controller. This can be used for generating expert demonstrations to train and evaluate imitation learning (IL) algorithms. -

Record large-scale demonstrations- One of the most powerful features of the Unity Editor is the ability to build a Scene to run on more than 20 platforms ranging from wearables to mobile and consoles. This enables developers to distribute their Scenes to a large number of devices (either privately or publicly through stores such as the Apple App Store or Google Play). This can facilitate recording expert demonstrations from a large number of experts or measuring human-level performance from a user (or player) population.

5 The Unity ML-Agents Toolkit

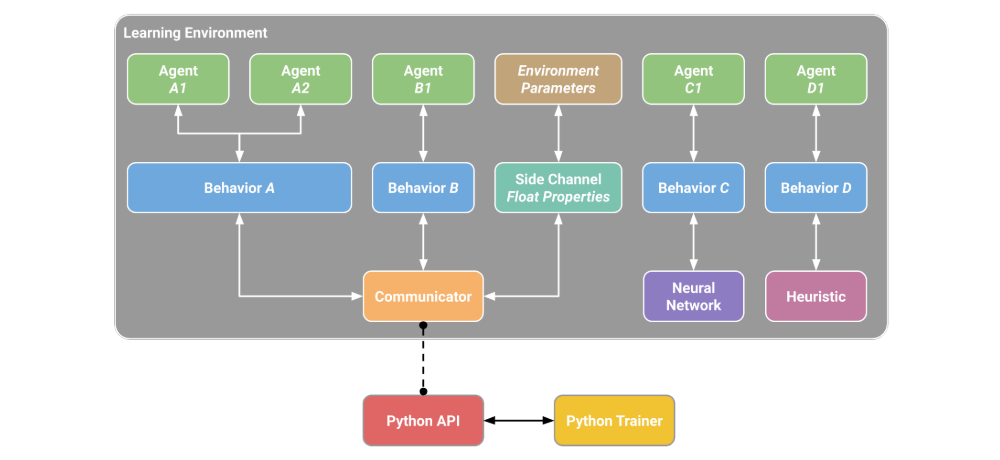

The Unity ML-Agents Toolkit is an open source project which enables researchers and developers to create simulated environments using the Unity Editor and interact with them via a Python API. The toolkit provides the ML-Agents SDK which contains all functionality necessary to define environments within the Unity Editor along with the core C# scripts to build a learning pipeline.

The features of the toolkit include a set of example environments, SOTA RL algorithms SAC and PPO, the IL algorithms GAIL and Behavioral Cloning (BC), support for Self-Play in both symmetric and asymmetric(非对称的)games, as well as the option to extend algorithms and policies with the Intrinsic Curiosity Module (ICM) and Long-Short-Term Cell (LSTM), respectively. As the platform grows, we intend to provide additional algorithms and model types. In what follows, we outline the key components of the toolkit as well as provide benchmark results with SAC and PPO on the Unity example environments.

Figure 2: A Learning Environment (as of version 1.0) created using the Unity Editor contains Agents and an Academy. The Agents are responsible for collecting observations and executing actions. The Academy is responsible for global coordination of the environment simulation.

5.1 ML-Agents SDK

The three core entities in the ML-Agents SDK are Sensors, Agents, and an Academy. The Agent component is used to directly indicate that a GameObject within a scene is an Agent, and can thus collect observations, take actions, and receive rewards. The agent can collect observations using a variety of possible sensors corresponding to different forms of information such as rendered images, ray-cast results, or arbitrary length vectors. Each Agent component contains a policy labeled with a behavior name.

Any number of agents can have a policy with the same behavior name. These agents will execute the same policy and share experience data during training. Additionally, there can be any number of behavior names for policies within a scene enabling simple construction of multi-agent scenarios with groups or individual agents executing many different behavior types. A policy can reference various decision-making mechanisms including player input, hard-coded scripts, internally embedded neural network models, or via interaction through the Python API. It is possible for agents to ask for decisions from policies either at a fixed or dynamic interval, as defined by the developer of the environment.

The reward function, used to provide a learning signal to the agent, can be defined or modified at any time during the simulation using the Unity scripting system. Likewise, simulation can be placed into a done state either at the level of an individual agent or the environment as a whole. This happens either via a Unity script call or by reaching a predefined max step count.

The Academy is a singleton(单例模式)within the simulation, and is used to keep track of the steps of the simulation and manage the agents. The Academy also contains the ability to define environment parameters, which can be used to change the configuration of the environment at runtime. Specifically, aspects of environmental physics and textures, sizes and the existence of GameObjects are controlled via exposed parameters which can be re-sampled and altered throughout training. For example, the gravity in the environment can fluctuate(波动)every fixed interval or additional obstacles(障碍物)can spawn when an agent reaches a certain proficiency(熟练度). This enables evaluation of an agent on a train/test split of environment variations and facilitates the creation of curriculum learning scenarios.

5.2 Python Package

The provided Python package contains a class called UnityEnvironment that can be used to launch and interface with Unity executables (as well as the Editor) which contain the required components described above. Communication between Python and Unity takes place via a gRPC communication protocol, and utilizes protobuf messages.

We also provide a set of wrapper APIs, which can be used to communicate with and control Unity learning environments through the standard gym interface used by many researchers and algorithm developers. These gym wrappers enable researchers to more easily swap in Unity environments to an existing RL system already designed around the gym interface.

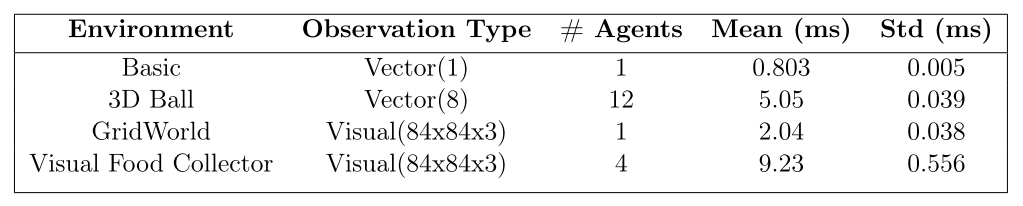

5.3 Performance Metrics

It is essential that an environment be able to provide greater than real-time simulation speed. It is possible to increase Unity ML-Agents simulations up to one hundred times real-time. The possible speed increase in practice, however, will vary based on the computational resources available, as well as the complexity of the environment. In the Unity Engine, game logic, including physics, can be run independently from the rendering of frames. As such, environments which do not rely on visual observations, such as those that use ray-casts for example, can benefit from simulation at speeds greater than those that do. See Table 2 for performance metrics when controlling environments from the Python API.

Table 2: Performance benchmark when using the Python API to control a Learning Environment from the same machine by calling env.step(). Mean and standard deviation in time averaged over 1000 simulation steps.

5.4 Example Environments

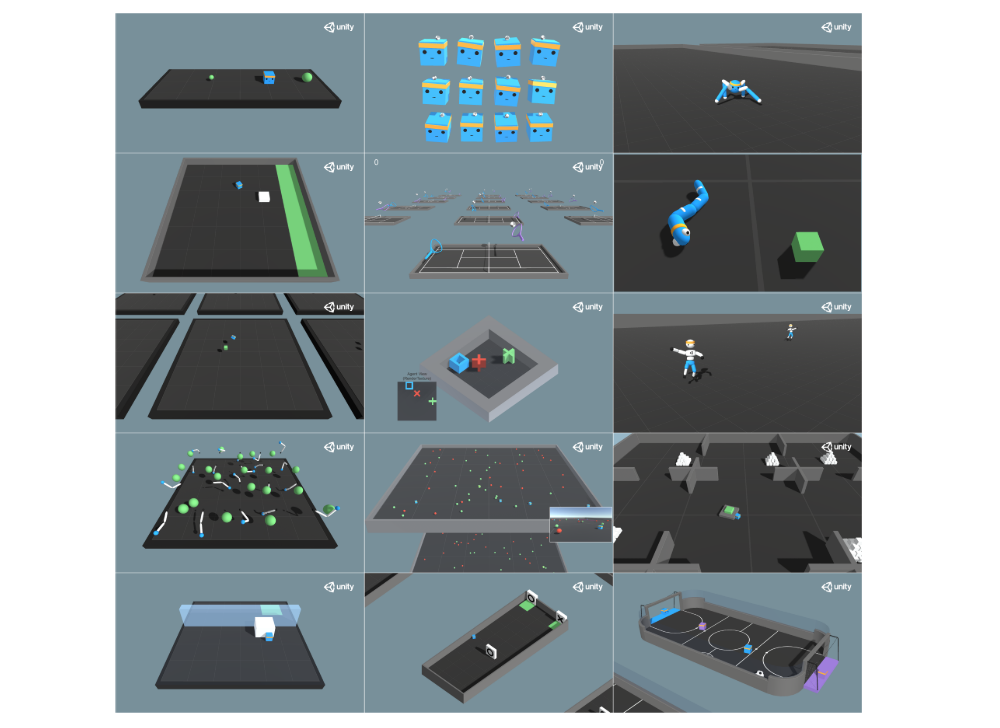

The Unity ML-Agents Toolkit contains a number of example environments in addition to the core functionality. These environments are designed to both be usable for benchmarking RL and IL algorithms as well as templates to develop novel environments and tasks. These environments contain examples of single and multi-agent scenarios, with agents using either vector or visual observations, taking either discrete or continuous actions, and receiving either dense or sparse rewards.

Figure 3: Images of the fourteen included example environments as of the v0.11 release of the Unity ML-Agents Toolkit. From Left-to-right, up-to-down: (a) Basic, (b) 3DBall, (c) Crawler, (d) Push Block, (e) Tennis, (f) Worm, (g) Bouncer, (h) Grid World, (i) Walker, (j) Reacher, (k) Food Collector, (l) Pyramids, (m) Wall Jump, (n) Hallway, (o) Soccer Twos.

For more information on the specifics of each of the environments, including the observations, actions, and reward functions, see the GitHub documentation. Trained model files as well as hyperparameter specifications for replicating all of our results on the example environments are provided with the toolkit. See other figures for baseline results on each example environment. These results describe the mean cumulative reward per-episode over five runs using PPO and SAC (plus relevant modifications)

6 Research Using Unity and the Unity ML-Agents Toolkit

In this section, we survey a collection of results from the literature which use Unity and/or the Unity ML-Agents Toolkit. The range of environments and algorithms reviewed here demonstrates the viability(可行性)of Unity as a general platform. We also discuss the Obstacle Tower benchmark which serves as an example of the degree of environmental complexity achievable on Unity. The corresponding Obstacle Tower contest(竞赛)posed a significant challenge to the research community inspiring a number of creative solutions. We review the top performing algorithm to show the rallying effect a benchmark like this can have on innovation in the field.

6.1 Domain-Specific Platforms and Algorithms

6.2 Obstacle Tower

The Obstacle Tower environment for DRL demonstrates the extent(程度)of environmental complexity possible from the Unity platform. This benchmark uses procedural generation and sparse rewards in order to ensure that each instance of the task requires flexible decision-making.

Each episode of Obstacle Tower consists of one-hundred randomly generated floors, each with an increasingly complex floor layout. Each floor layout is composed of rooms, which can contain puzzles, obstacles, enemies, or locomotion challenges. The goal of the agent is to reach the end room of each floor and to ascend(攀登)to the top floor of the tower without entering a fail-state such as falling in a hole or being defeated by an enemy. This benchmark provided a significant challenge to contemporary(当代的)RL algorithms, with baseline results showing test-time performance corresponding to solving on average five of 100 floors after 20 million time-steps of training. This is significantly worse than those of naive humans who have only interacted with the environment for five minutes and are able to solve on average 15 floors, and much worse than expert players who are able to solve on average 50 floors.

Figure 4: Examples of three floors generated in the Obstacle Tower environment.t